Marie Hélène Ndiaye, Dakar, Senegal

Marie Hélène Ndiaye clearly remembers when and why she became an activist. In high school, two students ran for president of the English club, a boy and a girl. «I voted for the girl because she was better than the guy.» Many other students felt the same way. When she won, one of the boys protested: «A lady won’t lead us.» A teacher then told the winning candidate: «Okay, no problem, let him lead and you will be the vice president.» Ndiaye decided to fight against this injustice. A few years later, she not only became president of her high school English club, but eventually founded her own English club and advocated for women’s issues. Time and again, people asked her to get involved in politics. «But I was not interested.» When she realized there were only a few jobs for women at the municipal level, she changed her mind. «The only women there did jobs like clean the building. So I said to myself, something needs to happen.» In 2014, at the age of 23, she became a city councilor, advocating for causes like better positions for women. Eventually, however, she experienced age and gender discrimination within her own party. «This was the same injustice I was fighting back in high school.» She left the party, and she intends to continue her political career in the near future as an independent candidate.

Daniel Langthasa, Haflong, Assam, India

For a long time, Daniel Langthasa didn’t think he would ever become a politician. One of the issues that kept him out of politics was the need to «compromise in some way or the other». «I was enjoying the freedom I had with my form of musical activism.» Using the moniker Mr India, Daniel Langthasa uses sarcasm and parody in his music to criticize politics and social issues, especially in his home region of Northeast India, a tribal area governed by so-called Autonomous Councils. In 2017, government employees in Langthasa’s hometown of Haflong went a whole year without salary. When they protested, the police resorted to violence and arrested some union members. «For a year, I tried making an impact, organizing protests, even in the capital, Delhi.» When he returned to Haflong, reflecting on all that had happened in the past 12 months, he made a decision: «We are trying to convince the people who are in power. It would be better to set an example and become a better politician.» He joined the Indian National Congress and was elected to the Autonomous Council. In 2022, after about four years, Langthasa left the party because he felt that many of his fellow members cared mostly about their careers, while issues that mattered to him, such as the environment, were being neglected. «My background was in activism. I wanted real change to happen, a change in politics.» Langthasa recently established a committee to protect the rights of indigenous groups in Northeast India. He is also involved in founding a new regional party.

Barbara Lochbihler, Berlin, Germany

In 2006, when Germany held the Presidency of the Council of the EU, Barbara Lochbihler’s task as representative of Amnesty International was to compile human rights demands and convey them to the German government. «In this context, I took a closer look at the European Union and its actions on behalf of human rights.» At the time, Barbara Lochbihler was the Secretary General of Amnesty International Germany. The topic of human rights has been with her since her college days in Munich when she joined an autonomous women’s group. This was her first involvement with women’s rights in Germany and the Global South. «Then, at the age of 50, I considered if and how I could make a difference on behalf of human rights as an elected official.» In 2009, Lochbihler ran for the European Parliament as a German Green Party candidate. Her intent was not to boost her career. «I just wanted to move laterally, not upward.» In the European Parliament, Lochbihler chaired the Human Rights Committee, among other responsibilites. She chose not to run again in 2019, but she continues to advocate for human rights, for instance on the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances and the International Commission against the Death Penalty. As vice president of the European Movement Germany, she remains dedicated to the EU: «Wherever I go, I try to advocate for the European Union. In a critical and constructive way, of course, but always in an effort to stem rising anti-democratic forces.»

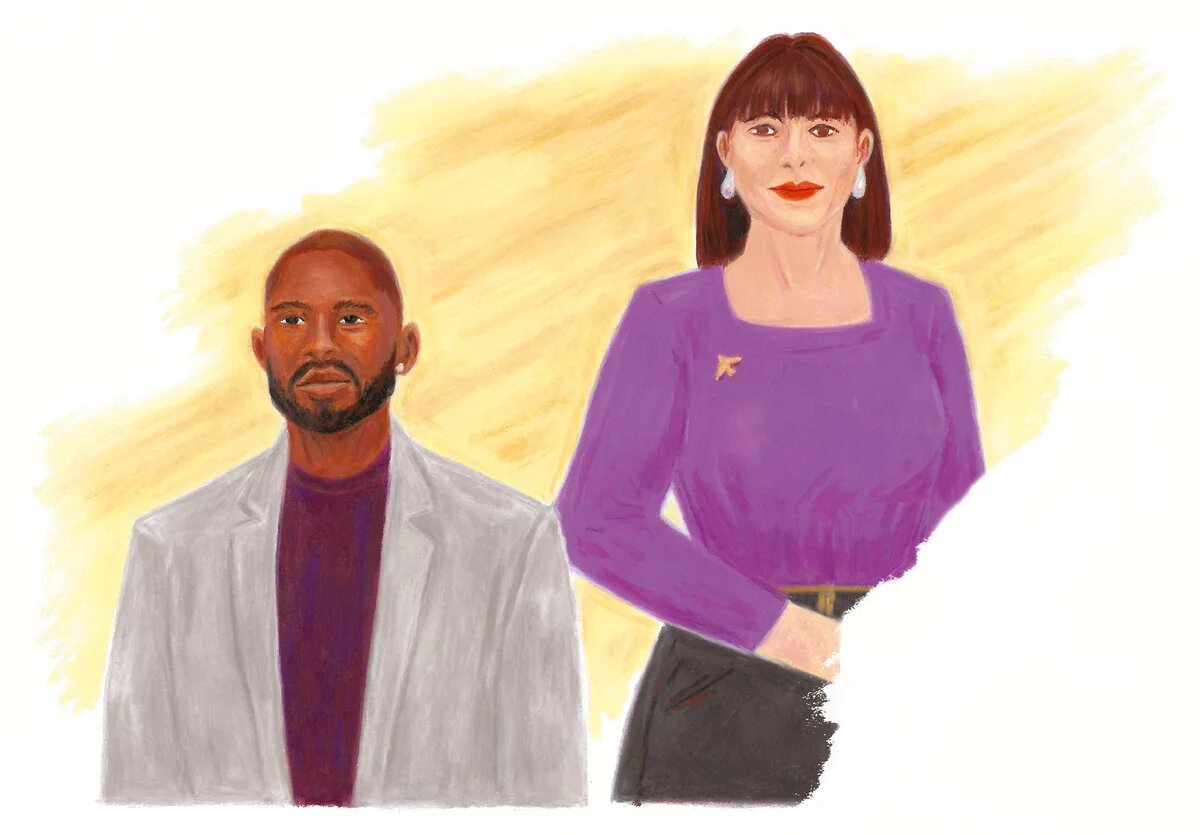

Mbali Ntuli, Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

From about six years of age, Mbali Ntuli knew she wanted to have an impact on society. Many of her family members were involved in social projects and often spoke about politics. In college, she was involved in the South African party Democratic Alliance. After graduating, she started her career in politics, serving as a city councilor and later as a member of the KwaZulu-Natal provincial legislature. However, over the years, she experienced her party as a toxic environment. Ntuli felt that the party leadership abused disciplinary procedures to control employees, among other things. Furthermore, Ntuli had major conflicts with a chairperson, some of them publicly. «I felt like a lot of what happened was against the values of the party.» In 2020, Ntuli ran for the position of the Democratic Alliance’s federal president, intending to transform the party. She lost the election, but continued to serve in the legislature of her province, KwaZulu-Natal. She remembers one night when she was writing a speech for the next day. «And as I was writing, I was thinking, I actually would rather do anything else than do this right now. I’d actually even rather die. I was really shattered by that thought because I would never, ever kill myself because I have a daughter.» Ntuli sought professional help for her mental health and left the party. «I felt like a great sense of relief not to be part of that bullshit any more. I still very much miss politics, though. But I’ve been able to transfer the skills from this period to the work I do now.» Currently, Ntuli serves as CEO of Groundwork Collective, a group she has founded to promote civic education and social entrepreneurship.

Mayor Kobi, South Fulton, Georgia, USA

One day as a young boy, Kobi was getting dressed to go to school when his mother told him it was a holiday. He didn’t know what she was talking about. His school didn’t celebrate a holiday that day. «She said, ‘It’s Martin Luther King Day.’ I asked, ‘Who is Martin Luther King?’ And she replied, ‘They’re not teaching you who that is?’ She was so upset.» That day, Kobi first learned about the civil rights movement. From that point on, Kobi was involved with different form of activism, eventually in the Atlanta chapter of Black Lives Matters. When he transitioned into politics around 2017, not everyone in the movement was convinced. «Some said: ‘I don’t know if we really believe in the political system like that.’ I told them: ‘I’ve been protesting with you all for two years. Every time we protest, we’re protesting an elected official, let’s just go take their seats.» In 2022, Kobi became the mayor of South Fulton, Georgia, a predominantly Black city. For Kobi, South Fulton could act as a role model for political change. «If there’s any place in America where we could really systematically start enacting these policies that we have been dreaming up in the Black Lives movement, it is this one. With a lot of progressive policies, people say: Oh, that sounds nice, but it will never work. On a local level, where stakes are small, you can show that it does actually work, and build up from there.»

Mila Carovska, Skopje, North Macedonia

«If you protest, doors will slam in your face,» people warned Mila Carovska. Carovska had worked closely with the Macedonian government for better healthcare and social policy as part of the NGO Health Education and Research Association (HERA). But when the government restricted the right to abortion in 2013, she decided to take the fight for reproductive rights - her own as well as those of other women - to the streets. Carovska’s activism attracted the attention of the opposition party, the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia. First, she headed their Commission for Social Policy. After the 2016 elections, she became Minister for Labor and Social Policy. Carovska fought hard for this position: «When you hold the pen, you get to decide and sign the right bills.» Initially, she experienced her work as a success. Before the election, she and the finance minister had agreed on social policy reforms. Together, they were able to implement a large portion of their agenda. Yet, in 2019, there were changes in the party, including a new finance minister. Carovska felt that from then on, politics revolved around corporations rather than people. «But I was still fighting for the same thing.» She continued her political career as Deputy Prime Minister of a transitional government, then as Minister of Education. In this position, one of her projects was to improve sexual education in schools. Carovska became a target of conservatives who spread false statements about her. In 2021, Carovska finally resigned. Despite of the difficulties she encountered in her political career, she is grateful for the experience. It has helped her in her current position as director of HERA, the same NGO she worked for before embarking on her political career. «Any information about the system and the political process is invaluable. There is no other place where you can learn all of this. Now everything is much easier for me.»

Christina Focken is a freelance journalist living in Berlin, where she majored in Gender Studies and Regional Asian/African Studies. Her Master’s degree in Global Studies also took her to Bangkok and Buenos Aires.

Illustration: Marie Guillard