Interview by Rasmus Randig.

A few years ago you said in an interview that you dreamed of a dignified life in Morocco, of living in a democracy. What has become of this dream today, in June 2024?

The dream is still a dream. In order to say we live in a democracy, we would have to answer in the affirmative to the following questions: «Is there a separation of powers? Are the judiciary and the executive intertwined? Do we have a high level of freedom of expression?» We still have a long way to go.

And to get there, you work for the Theater of the Oppressed. Can you tell me what it is, exactly? What kind of work do you do?

The Theater of the Oppressed is a theatrical methodology invented by Brazilian playwright Augusto Boal in the 1960s and 1970s, during the dictatorship in Brazil. It is a form of theater that enables audience participation. We call the audience the «spect-actor»: The audience watches, but also takes part in the action. It is a theater that encourages people to think, but also to take action towards change. It raises issues and works with the audience to find solutions and alternatives.

How exactly do you do that? Do you have a special technique?

We specialize in what is known as forum theater, which primarily means generating a certain group dynamic. It’s not the kind of theater where a director has an idea and then recruits actors to execute it. Rather, the whole group is involved in the process. Forum theater also means that we train and educate. Every year, we offer an open workshop, for instance. People from remote areas of Casablanca come to us for training.

Paint a picture for us, which piece are you currently performing?

We currently have two focal points. For one, we play a piece that has been around for a long time, which we have often done with the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. It is called Le conte des nez (The tale of the noses). It’s about accepting others, about migration, and differences. This is perhaps our most famous or best-known piece, which we take on the road all the time. And then, over the last two years, we also addressed violence against women during the Covid pandemic. This piece is called Il n’y a rien à prouver (There is nothing to prove).

You were part of the protest movement in Morocco that began on February 20, 2011, so you have been politically active. Was there an experience or key event that made you switch to theater and the arts after one year?

I‘ve done theater before. Prior to February 20, I spent five years in Barcelona, Spain, where I trained in the Theater of the Oppressed. In the year of the protest movement, I was on its communication committee because I speak Arabic, French, and Spanish. After about a year, the demonstrations began to die down, and the numbers of active protesters dwindled compared to the onlookers. We marched through the streets, and people watched us.

Was it this that made you look for a different path?

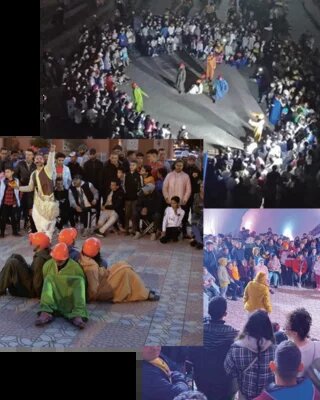

It shocked me at the time, and I thought: «I know the Theater of the Oppressed, why not propose it to young people?» They were very motivated to try something new after all the bad experiences. So we started rehearsing in the room where we held the movement’s general meetings. After three or four months, we took to the streets and started the work that we continue to this day.

Now, more than a decade after the events and a decade of theater, has your work made a difference compared to what you experienced in 2011?

I‘d be lying if I said we made a big difference at the macro level. But on a micro level, we achieved a lot. I think we made Moroccan civil society aware of forum theater, or culture in general, as a driver of change, or to develop projects that foster change. Not as the icing on the cake or the final presentation of a project. We try to convey that art and theater can help drive social and political change, and, at the very least, be an outlet for people to voice criticism and form an opinion. I think we have stirred many debates, and we continue to do so.

Speaking of stirring debates: Can you give me an example, a topic you have launched with the audience at your theater?

About seven or eight years ago, we held a day about democracy, corruption, and the Moroccan justice system. In our play, there was a judge who was about to pass a verdict, but then he received a phone call – was someone trying to influence him? This was the moment we engaged the audience. We asked them: «What will the judge do when he takes this call?» A lot of people didn’t want to speak, but I’ll never forget this one man, whom we called «the neighborhood lunatic». He spoke up, the judge rebuffed him, and he replied: «No! I’m not the problem. You have to find the one who called.» Everyone began to applaud. At a micro level, the aim is to raise awareness. That may not seem like much, but it means a lot to us when people realize that there’s a collective consciousness, because people are willing to open their eyes, voice criticism, and form an opinion.

Have you ever considered other kinds of committment? As a journalist, for example, or in an established or new political party?

I tried working for a political party, but after a year, I couldn't do it anymore. By the second or third meeting, I knew that this was not my thing, simply because there were so many discussions. My friends know that I often call that «language production». It seemed strange to go from one meeting to the next, from one press release to the next. That wasn’t my world, but there are other young people in this movement who have taken this path and are doing well.

Does theater facilitate things that politics can’t - and vice versa?

From my point of view, politicians make decisions on behalf of others, whereas in this kind of theater, decisions are made collectively. Here, in Morocco, the only time we see our politicians is during election season. They are a bit distant. What theater can do is reduce the distance between the decision-maker and the audience, or even eliminate it altogether, and move on to action. Politicians, even the ones who do listen, are the ones taking action alone on behalf of others. That doesn’t mean that politics is bad per se, it also has a role to play at the macro level. It can advocate at an institutional level. It can discuss topics in parliament. It can get things moving in the communities. If you pursue genuine politics, that is.

In the European elections, many young people voted for far-right parties. How can we get them to debate matters openly, and not just on fragmented social networks?

There’s a difference between truly supporting someone and being the wise or all-knowing man who tells you what to do. We have the feeling that it is still the wise man who is telling us: «This is good for you, and this is not good for you.» Moroccan youth are becoming increasingly sensitive to this paternalism. Youngsters have to listen to their parents, their school, their institutions. If an agent of civil society or change shows up and starts patronizing these kids, they will resist.

What exactly does good «support» look like?

You have to let young people dream, trust them, and above all, let them make their own mistakes. That’s the way it is in politics: Anyone who governs for a long time, or governs at all, makes mistakes, and those who do nothing are off the hook because they’ve done nothing. That’s dangerous, especially when young people vote that way. We have to create spaces for them. We have to let them make their own mistakes, listen to them, guide them, but not play educator, parent, or teacher - else we will lose them.

Hosni el Mokhlis is a stage director. He also serves as artistic director of the Theater of the Oppressed in Casablanca and of the Gorara Association for Arts and Cultures. At the same time, he works as a coach at the Forum Theater and acts as a consultant to numerous cultural projects.

Rasmus Randig is Head of Program for International Democracy and Deputy Head of Unit for Global Support for Democracy and Human Rights at the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung in Brussels. He studied Economic and Social History in Glasgow and Constance and worked in Crisis Prevention and Stabilization at the German Foreign Office.