What happens to refugees on their way to the European Union? Serbian novelist Vladimir Arsenijević has travelled the Balkan route and kept a diary of his journey.

1. Prologue: Border crossing Šid-Tovarnik (25/09/2015, 17.20 h)

Fifteen hastily abandoned tents are scattered in disarray on a small portion of no man's land between Serbia and Croatia. All over trampled mud on which different shoe-prints can be discerned lie piles of uprooted sugar beet. The place is virtually littered with various personal items - pieces of clothing either forgotten or discarded in haste, pale pink mats printed over with big blue letters saying UNHCR - THE UN REFUGEE AGENCY, brochures published by Alliance Biblique Universelle with selected suras from the Koran printed in Arabic script, muddy leaflets also in Arabic, containing maps of Southeast Europe, lists of refugee camps and reception centres, phone numbers, email addresses and other similar information, half emptied cans of beans, sardines or tuna, plastic water bottles, boxes of biscuits, disposable plates, children's diapers and toys, banana peels, crumpled cigarette packs.

The overwhelming silence convincingly testifies to the speed with which this makeshift camp was abandoned. In a ghostlike atmosphere that still lingers after everyone has left in haste, it is hard to imagine that only a few minutes earlier it was swarming with people. One thing, however, is quite certain: no one will ever miss it.

A week ago Croatia closed shut all its borders with Serbia in sheer panic over the growing wave of refugees redirected here after the Hungarians decided to impose tough and non-wavering measures against further entrance and passage of the migrants through their territory. Ever since, more then a thousand refugees gathered in the bleak vacuum of the intermediate zone. For a whole week, this narrow stretch of hard Pannonian soil represented their whole wide world. And the only thing all these people could possibly hope for was that sooner or later something would happen that would once more allow them to continue further with their long and arduous journey.

And then this long awaited "something" actually did "happen." On Friday, September 25, exactly at 5 PM, border-crossings were officially re-opened. Minutes later the Croatian authorities arrived to this place with organized bus transport. Within one quarter of an hour all of the refugees were swiftly loaded into vehicles and taken over to the Croatian territory.

There they were placed in the refugee centre in Opatovac, registered and classified, provided with food, hygiene and medical care. Soon after they were divided in groups, boarded on trains and dully sent further, in a direction apparently unknown to everyone, including themselves, but certainly towards one of Croatian borders with neighboring Hungary.

And so, already at 5:20 PM, not a living soul remains in this place. Completely on our own, we are free to wander around aimlessly among the deserted tents and to rummage as much as we like through the pile of colorful left-overs strewn all over this patch of land between the small border-town cemetery gate on the Croatian side and monotonous, barren fields of sugar beet on the Serbian side of the border.

2. On Blind Hope

This is exactly how after full seven days of downtime the unofficial interstate highway that runs through this part of Europe (formerly known as Yugoslavia and nowadays mostly referred to with the series of seemingly neutral euphemisms as "the Southeast", or "the Western Balkans") became passable once more. It is now continuously used by endless thousands of refugees who are heading across towards the heart of Europe in the hope that they shall eventually find what every living thing certainly deserves: just a tiny little bit of personal happiness.

As for us here, with our daily lives so hopelessly hectic and with such mind-boggling variety of bombastic media content that we have to deal with, it is no wonder that we find it very easy to overlook even the very existence of this dramatic migrant route. One can simply decide never to turn from ones planned travel route and the journey will pass in blissful ignorance. Plains, hills and mountains will idly stroll by ones eyes. Gas stations owned by large global corporations, roadside restaurants and polluted tollgates will rhythmically rotate on both sides of the road. Literally nothing will point out, not even for a single fleeting moment, that the event as dramatic as anything that Europe has ever had a chance to witness is happening just around the corner - one of the biggest human migrations in history.

The Highway to personal happiness links Turkey, Greece, Macedonia and Serbia, connects them with Hungary and Croatia and leads inexorably on and on towards the desired refugee destinations such as Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Great Britain and Sweden.

So if the refugees manage to cross over the northwestern part of the Aegean sea on their tiny boats and rafts from the Turkish port of Izmir to the nearby Greek islands of Lesbos and Kos, they will certainly also find a way to be transferred from there by regular ferry-lines to Athens' port of Piraeus. Buses will then take them further towards the northern Greek border with Macedonia and the refugee camp on the outskirts of the border town Eidomeni. From there, under the watchful eye of the Greek and Macedonian border police, they will move over to Gevgelija on the other side of the border and than use trains to travel to the tiny village of Tabanovce right on the very border with Serbia.

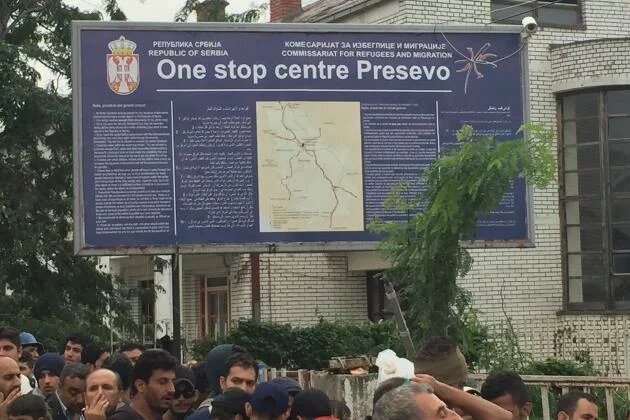

A few kilometers away lies the village of Miratovac where the temporary refugee camp has been set up and several kilometers of dirt road further on will bring them to the so-called "One-stop centre" in the nearby town of Preševo. If by that point still some money has miraculously managed to remain in their pockets, they will from there be able to move to the Serbian capital Belgrade or else directly to the border town of Šid from where they will cross to Croatia and thus once more find themselves in the EU and Schengen zone. And from that point they are actually only a few steps away from reaching the final goal of this long journey that they traversed driven by faith in a possibility of a better life fueled by the legendary prosperity of the welfare states of Western or Northern Europe.

"Ah, well I know how exiles feed on hopes," says Aegisthus, the son of Thiestes, lover of Clytemnestra and the murderer of the king of Mycene in the tragedy "Agamemnon", the first part of the famous Aeschylus' trilogy of tragic dramas "Oresteia". Aeschylus' tragedies originate from the fifth century BC and the motive of refugee in them is quite common.

The refugee drama, of course, exists from the dawn of our flawed civilization largely based on mutual divisions, wars, enslavements and, of course, the expulsions.

In the records preserved from the very beginning of the written word we encounter distressing verse and sentences about hardships of apostasy, unrootedness and exile. Pain, fear and powerlessness keep traveling together with millions of refugees who roam the planet since times immemorial. Blind hope also, the one that the Titan Prometheus presented to humanity together with the gift of fire. It is the one refugee asset that can be neither taken away from them nor robbed. It is, to put it plainly, non-exchangeable. They can only loose it somewhere along their way and that is the reason why they protect it so jealously, much more than anything else they possess.

3. In and around the refugee camp Eidomeni

The endless line of buses stretches along the dirt road that leads to the main entrance of the camp Eidomeni in the far north of Greece. In the sticky dust that got caught all over their bodywork someone wrote with finger an ominous word "KOBANE".

This town - Kobanî - is located in Western Kurdistan, on the border of Syria with Turkey. From 2012 to 2014 it was under the control of the Kurdish militia YPG (People's Protection Units), famous Peshmergas, "those who confront death", only to be later held under siege for over six months by the notorious forces of ISIL. During this period the entire half of the town was completely destroyed.

After several terrible massacres perpetrated mainly in the surrounding villages and directed against Kurds, even though they also affected members of other local minorities, such as the Turkmen and Armenians, many terrified civilians fled to Turkey, where they were placed in the border camps. Today Kobanî once more belongs to the Kurdish-held territory and refugee population is slowly returning from Turkey back to Syria and Western Kurdistan. However, many among them decided to head in the opposite direction, towards Europe.

Unlike all other refugee focal points that we visited on our several-day journey through the Balkan part of the Highway to personal happiness, Eidomeni camp looks almost decent: relatively clean paths among the lines of long white tents and rows of neatly lined heavenly blue mobile toilets. Besides that, and also in huge contrast to all other similar places throughout the region, this camp is kept wide open and completely unsecured. Literally anyone is free to walk in without any special permits or press credentials.

The prevailing sense of chaos provokes dizziness. International volunteer workers with bottles of water or iPhones in their hands and rucksacks on their backs are freely bringing their friends over for a tour, journalists keep snooping around, reporters and cameramen are tirelessly photographing and filming anything that moves, curious travellers are using the opportunity of quite an unusual tourist experience - there is something insanely lively, maybe even playful in the loud chatter that is constantly reaching us from all sides at once.

In the midst of all that, we encounter a local activist Vassilis Tsartsanis. He stands on a plateau not too far from the entrance to the camp addressing in the loud voice a group of mainly black-clad representatives of the German Protestant denominations led by theologian Ulrich Lilie, the current president of Diakonia, the humanitarian organization of the German Evangelical Church.

As the group is taking notes and in the same time smiling kindly to Tsartsanis, he keeps on trying to convince them that on the top of the power-pyramid in the EU is not, as commonly thought, the Brussels administration, but, on the contrary, international mafia whose main profit-making activity nowadays is human trafficking. According to Tsartsanis, it is the main generator of modern day refugee migrations.

"The mafia controls the flow of refugees into Europe," he thunders while addressing his awed listeners. "It opens and closes the borders and determines which roads, when and how the refugees will take."

Representatives of the Protestant Churches of Germany are listening to him with indisputable attention and, it also seems, with equal level of non-understanding. We can decide to accept this simple message of Vassilis Tsartsanis or not. We have the full right to agree or disagree with him. Nothing easier than to smile and shake our head wisely just like this group of Evangelical humanitarian activists. It is however difficult, almost impossible - despite the abundance of information, or perhaps exactly because of it - to conclude with full certainty what exactly triggered this wave of refugees who are for the past several months in huge numbers crossing the Balkans towards Central and Western Europe.

Navid Kermani, a leading German Islamologist of Iranian origin, and a renowned writer in whose company we accomplished this journey, thinks that it was most likely influenced by the recent change in the EU policy towards the Frontex agency. Its ships in the Mediterranean Sea who are from spring this year operating under a new mission entitled "Triton", no longer intercept boats carrying refugees from Middle Eastern Libyan coast to the Italian island of Lampedusa which turned into a symbol of the refugee saga because of the huge number of victims taken by this deadly crossing on an almost daily basis.

"This change was provoked by the sharp shift in public opinion and pressure from both the civil society and the European Parliament" Kermani tells us. "That is, however, only one of the reasons. The second reason is, of course, the war in Syria where people lost almost all hope during last year, realizing that the ISIL is already there while Assad hasn't gone anywhere, but only started to use even more bombs. And finally, this summer Germany was forced to open its' borders because of all the unbearable scenes coming from the Balkans and Hungary. It was a clear signal for many refugees to embark on this journey, particularly those from Afghanistan. Today, when the fall of Kunduz is practically inevitable, an ever growing number of Afghans will attempt to reach Germany, which is ready to receive the entire one million refugees but not much more than that."

Whatever it is that launched this wave, one thing is definitely certain - it constantly becomes more and more powerful. Nowadays it already reaches the scale of the tsunami. While only a fortnight ago about 1,500 refugees passed this route each day, by the end of September that number soared to as much as 5,000. Five thousand human souls a day. Men, women, children, elderly people, pregnant women, the sick, the disabled. In a word - civilians.

5,000 - this number kept reappearing in many conversations we held along the refugee road, or at least in the part that we passed on our journey. It was repeated, along with intense head-nodding, by the police officers, medical workers, forensic experts and representatives, activists and volunteers of various governmental and non-governmental organizations on the ground alike.

4. On the road to Gevgelija

On the other side of the Greek-Macedonian border, a stone marked with an acronym SFRJ (Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia) still stands firmly almost a quarter of a century since the country whose southernmost border it once marked ceased to exist. But after the recent establishment of this temporary border crossing intended solely for refugees, it is surrounded by the coils of barbed wire in such way that it now appears to be in Greece.

This, however, does not seem to bother anyone here in particular. When we mention this to the young member of the Macedonian military police, with whom we are idly chatting in this early, chilly September morning, he just vaguely shrugs while nonchalantly leaning on his automatic weapon hanging around his neck. His eyes are firmly fixed on the new group of refugees laden with personal possessions that is right now appearing on the back exit of the Greek camp maybe a hundred meters away from us.

Arranged in a neat column they are slowly moving towards the crossing but are then routinely stopped halfway by the Greek police.

They have to wait there, in no man's land, under a huge sky covered with the swollen and swirling dark clouds, for the green light from the other side, in order to move on. This group of people, which we observe with unconcealed interest, is just one of many similar groups of fifty persons that appear at the back exit of the Greek refugee camp every twenty minutes in order to cross on foot the short path from Eidomeni to the similar camp in neighbouring Macedonia.

Among them we discern men, women, whole families with children, young and old alike. They are clad surprisingly well, in a new and contemporary, even fashionable clothing items: Adidas jackets, Nike sneakers, sturdy backpacks on their backs. It is easy to distinguish people belonging to different class, educational level and ethnic origin. The majority of them are Syrians and Kurds, but there are also Iraqis, Afghans and Africans, mostly from Eritrea or Somalia, Nigeria and Sudan.

We have already heard from a number of interlocutors disturbing accounts about hostilities that exist between some of the refugees. We learned about the organized gangs of Afghans who are robbing wealthier Syrians with the help of local criminals on both sides of the border and the corrupt representatives of the Greek and Macedonian police. None of all this, however, are we able to observe while we walk together with this colorful group toward the camp on the Macedonian side of the border. Muddy road stretches along the endless vineyards intersected by deep puddles of rain that was relentlessly falling all night.

Prevalent peace and quiet is disrupted only by local traders who in this wave of refugees spotted a unique economic opportunity that shouldn't be missed. While they offer bunches of bananas, bottles of water and packs of cigarettes to the passers-by, they keep shouting in their faces: "Turkish lira OK! Turkish lira OK!"

"They should all be arrested,"Milena Berić, organizer and main coordinator of our trip, grits her teeth while in the same time trying not to look at exerted, insincere smiles on the traders' faces.

Refugees also pass them by in silence and with their heads bowed. Only some of them actually bring money out of their pockets to buy a thing or two, mostly cigarettes. They pause just to light a cigarette and then quietly move on, thoughtfully puffing smokes.

As we approach the camp in Gevgelija, Macedonian police awaiting us in a line formed in front of the main gate, the young green-eyed Syrian named Bashar stops for a moment to explain to us that the people in this group need neither cigarettes nor bananas. "None of all that," he says politely and with gratitude in his voice, as if the cigarettes offered to them aren't three times more expensive than those in the kiosk while bananas can only be purchased at an astronomical price of one euro per piece. "We are grateful to you for everything," he adds wearily in fluent English and with a slight bow, "but we just want to pass through your country and continue on our way to safety."

When we ask him where he's heading, he explains that he, unlike many in this group as well as in all other groups before and after it, does not want to go to Germany. No, his goal is the United Kingdom. He is a professor of English and a few months ago, after escaping from Aleppo, he ended up in Turkey, where he tried to earn enough money for this journey by giving private language lessons. Ten days ago his friend left and when he received his call from Western Europe he finally dared to embark on his own. His green eyes glint when we wish him luck on the rest of his journey. "Thank you," he says once more with a smile and then continues to pace energetically "on his way to safety," led by his grand plan and indestructible, even if blind hope.

5. Miratovac and onwards

"We urgently need medical vehicle," blonde young woman in an orange vest with inscription UNHCR printed in big white letters is yelling into her cell phone. "Right now, that's correct, right now! What part of it do you find hard to understand? Well, she's already in labor pain!" She puts the phone down with a desperate look on her face. "They simply don't care," she sighs with despair in her voice as persistent drizzle keeps hitting her face.

In a tent not too far from where we are standing, under the grim light of a bare bulb, we spot a pregnant woman of indeterminate age wearing a hijab and glasses. Her husband dressed in a leather jacket and plaid pants and their two children, a boy and a girl, are sitting patiently beside her.

Our sense of panic is almost tragicomically contrasted to the apparent peace that prevails among the members of that family. Even the expression on the woman's pale face seems somehow blissful.

Only occasionally her cheeks tremble with sudden spasm, showing the pain that she must feel and suffers mostly in silence. At one point, she looks directly in her husbands' eyes and keeps at it so long that we cannot help ourselves but to think that she is actually saying something to him, something significant that only the two of them can understand.

A barely visible glow resembling an inner light then appears on her weary face. It might be a tiny sign of happiness because of this child who is on its way in spite of everything, determined to be born in the middle of storm and refuge, amidst and against this whole tragedy in which their small, powerless family got entangled. Or maybe it could even be a glimmer of hope, we think immediately afterwards, this time invested in the thought that she and her husband just might be able, if there is at least a little justice left in this world, to provide for their future child something better than this miserable reality that was granted to them.

Of course, it is quite possible that we simply made up all of this. The scene in the tent was hardly visible because of the rain and all those committed activists of international organizations, overworked medical workers and armed police that kept buzzing around us. Anyway, the woman wearing the hijab quickly looked away and with an expression of indescribable weariness buried her face in her palms. Her husband closed his eyes and continued to rub his temples with trembling hands. Medical vehicle was nowhere to be seen and the rain kept hopelessly pouring down.

Highway to personal happiness, of course, has its own distinct streams and flows. These are quite powerful and do not allow refugees to maintain for too long on any of its intermediate positions.

All the people we encountered in Miratovac have despite strong wind and heavy rain already passed on foot the distance of three kilometers to the Serbian side

of the border from Macedonian village of Tabanovce where they were delivered from the camp in Gevgelija by state-organized trains. From there, they need to pass yet another stretch of two and a half kilometers to the main refugee centre in Preševo. Although several vans continuously transport refugees from one place to another, there is simply too many of them and preference is given to women and children, as we found out from the kind activists of IOM (International Organization for Migration).

However, on our way to Miratovac we were passing by a long line of people heading on foot to Preševo and so we tentatively notice that there were more then just men in that group. Trying to protect themselves from the rain under transparent raincoats of different hues, many women and children kept painstakingly progressing towards the next point of their route together with their fathers, brothers and husbands.

While we watched them from the warmth and safety of our small vehicle that headed in the opposite direction through more and more liquid mud on the unpaved road, Moises Saman, a photographer who also went on this journey with us, tried to capture their exodus by photographing the migrants through the windshield all covered in raindrops. A huge darkening sky in front of us and silence through which only the sharp pelting of rain and arhythmical and syncopated snapping of his camera could be heard, only contributed to the sickening feeling that reigned in the car in those moments.

When we pointed that out during our conversation with IOM activists in Miratovac, one of them quickly explained to us that for the majority of refugees the greatest fear naturally represents an ever-present possibility that something might separate them from their loved ones and that then they will no longer be able to meet them again. "So they stick together at all costs," he said briefly with a hollow laugh. "Everything here is pure drama," he added before parting with us to help out the refugees board in the vans which finally came for another turn.

Soon after, even the long awaited medical vehicle also arrives. The group of activists led by a blond woman in an UNHCR-vest are helping a pregnant woman, her husband and children to board through the double rear doors. They will be taken to the hospital in Preševo where she will give birth and in case of any complications they will be transferred to a proper maternity ward in Vranje. "All of you", they are quick to reassure them.

"We see that families stay together in all situations," says the blonde woman to us while looking at a vehicle that is quickly taking off. Its flashing lights will soon be lost in the darkness. We also look at it as long as it is visible and breathe deeply. Again, we hear children crying from somewhere. The next group is already soaking wet while they are patiently waiting for those same few vans to transfer them to Preševo. IOM and UNHCR activists continue to help them. Tirelessly and without a break they move about their business in this persistent heavy rain that simply refuses to stop pouring.

6. One-stop centre Preševo

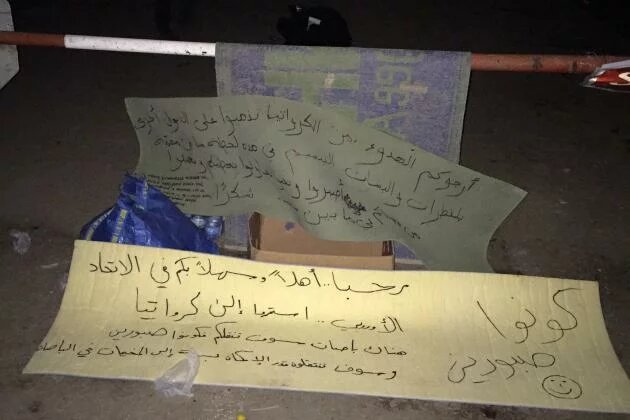

The same sense of drama is also constantly present in the so-called "One-stop centre", set up by the Commissariat for Refugees of the Republic of Serbia in the near-by town of Preševo. Chaos at the main gate, the refugees crowded in the narrow passage enclosed by metal bars, armed guards with medical masks over their faces, high pitched tension among the already exhausted travelers eager to move on as soon as possible, heaps of garbage strewn everywhere - all that leaves the dreary impression on a visitor.

Accompanied by the official representative of the Commissariat for Refugees of Serbia we observe the process of registering new arrivals in a long tent through which they keep passing one by one as on a treadmill. They exit on the other side beaming, holding plasticized numbers in their hands. A young mother with a bewildered look on her face approaches us. She is holding a blond toddler in her arms. In an effort to get some kind of help and support, or at least a bit of understanding, she attempts to explain to us, using body language as much as words, that her husband was physically attacked by a group of Afghans in front of the camp. In a brawl that broke out, her child was also injured. Indeed, toddlers left eye is visibly red and swollen. After the police intervened, she was forcibly separated from her husband and is now excitedly begging us to reunite her with him.

Deeply shaken, we ask our official companion to help her. But she is worn out by her sixteen-hour daily shifts and constant contact with the refugees and their various problems and no longer seems able to emotionally respond. "They often lie in order to get what they want," she says, her voice exasperated. "They are capable of pinching or hitting their child in order to make it cry so that they can then require an extraordinary passage and medical care," she continues, aware of disbelief on our faces.

A young mother is anxiously watching us as we speak in a language totally incomprehensible to her. "I cannot help her," our companion waves her hand wearily, "she has to be patient and wait." Then she addresses her in English. "Your husband will arrive," she pronounces slowly. "Do not worry." But a woman with a child only shakes her head weakly - she does not seem to understand. "I cannot help her," repeats our tired interlocutor. "I used to try and provide help to all but that's impossible. There are simply too many of them."

Human kindness and desire to help everyone is all too often confronted with a pervasive fatigue and general nervousness here in the field where no one has neither the time nor the energy for excessive niceties.

Literally everyone we met among those who in one way or another deal with refugees seemed equally exhausted, overworked and on edge. Yet, we nevertheless often testified to various examples of human kindness that is capable of overcoming all limitations and obstacles and that constantly kept seeping through the tight net of misery that surrounds the refugees on their way to personal happiness. The officer who inspects the newcomers baggage before they are allowed to pass into the camp, for a long time patiently shakes hands with a small boy who is all the time laughing resonantly, eager for at least a bit of attention and joy.

The older gray-haired man with the Red Cross insignia on the jacket holds in his arms a child that, when a mother tries to take it over, only presses its tiny little body more strongly against him. He deeply flushes despite his years, and a big smile lights his face as he is not able to hold it back. "She knows quite well whom she got these new shoes from," his voice trembles and he seems to be on the verge of tears while he gently caresses little girls hair. Even her mother seems touched when her baby lovingly lowers her head into the base of his neck.

Two young friends, one of whom is on crutches because of an injured left foot, do not separate even for a moment.

The injured one is constantly leaning on his friend, they are slower than many, each queue passes them by. Finally an armed member of the gendarmerie in a camouflage uniform approaches and escorts them to the beginning of the line. Gratitude on their faces is indescribable but he is already busy with something else.

In the only brick building within this camp, forensics are taking fingerprints of all refugees over the age of eighteen. They are then photographed and finally issued the necessary paper that allows them to continue with their journey. As we contemplate the poster hanging on the wall that shows a detailed map of this part of Serbia with "hazardous areas contaminated by mines, cluster ammunitions and other unexploded ordnance" that remain here ever since the NATO bombing of 1999, a young Afghan man passes by. He seems barely older than a boy. We take pictures of him proudly showing a document he has just been given. Below the inscription in Cyrillic letters reading "Confirmation of intent to seek asylum" is his name "Mujeeb Mouahed", his sex "male" and finally his date of birth "01.01.1995". In the next column, intended for the information about the type of document that an asylum seeker carries, we read just a short note: "Without a passport."

Nevertheless, Mujeeb is radiant. The smile on his face is contagious. We smile along with him and clap him on the shoulder in a gesture of congratulation. He has neither money nor passport but, hey - who cares! He was issued a necessary document and his journey can now continue.

7. On Overpowering Goodness of Humankind

Although the Serbian capital Belgrade for months on end represented the inevitable stop-over on the refugee route through the Balkans, a place where many of them lingered at least for a while in order to have a rest and wait for their friends or relatives from Western countries to send some money via Western Union, in recent times, after the closing of the passage through Hungary and the simultaneous opening of the Croatian border, it seems to have lost its importance somewhat.

As we have just witnessed during our short stay in Preševo, the refugees are now mostly moving directly from the south of Serbia to the border with Croatia near Šid. They do it either by buses or, if they can afford it, by taxis. And the price? Well, each taxi-ride is separately arranged in direct discussion with the drivers who seem to be almost miraculously capable of hinting the negotiators' financial possibilities. On the other hand, the official price of a bus ticket to Šid is thirty euros according to the representative of the Commissariat for Refugees. The unofficial one, however, offered to us by the drivers and conductors of numerous buses parked in front of the "One-stop centre", seems to be a bit higher - thirty-five euros. In these informal five euros surplus lies the very essence of brutal economy that rules along the Highway of personal happiness.

But not everything is so black. Everywhere along the route we also witnessed many examples of selfless human kindness. We noticed them in Gevgelija, Miratovac and Preševo and we also noticed them during our stay in Belgrade. There are still a lot of migrants in the two shabby parks near the railway and bus stations. "Today much less than before, though," according to Vladimir Puača, a coordinator of the Refugee Info-centre in Nemanjina street. "Perhaps only a few hundred." But even this number is enough to completely fill the two parks with people. They mingle freely in the gray morning after a rainy night, among the usual site of tents, UNHCR blankets and rubbish strewn just about everywhere.

We also saw a sizable crowd in front of Miksalište, Belgraders' favorite concert space that was, thanks to the quick reaction of the cultural institution Mikser House, in recent months turned into a centre for migrants. This unofficial space employs a group of about fifty volunteers from seventeen countries and offers to those in need showers with hot water, private room for breast feeding, washing machines, new clothes and shoes, bottled water, food and any other supplies that they might possibly need together with medical help and important information.

After a short visit to Miksalište we return to the park and stop for a while to observe a group of boys who are happily playing football in one of the corners. When we ask them for a photograph, they seem to be more than glad to respond to our invitation. They hug tightly so that all can fit in the frame and face the camera with huge smiles and sparks in their eyes. Most of the children we met on this trip appeared quite cheerful and lively. Perhaps this arduous journey with an uncertain outcome that must seem like hell to their exhausted parents, feels like a great life adventure to them.

While we are showing them photos and enjoying their happiness and laughter, we cannot but wonder in which way and from what kind of circumstances will they remember details from their journey along the Highway to personal happiness when they once grow up.

Another point at which refugees can gather information, called Info-Park, is organized by the B92 Foundation and located, as its name suggests, within the park. Always attentive activists, consisting mostly of Belgrade residents of Arab origin who speak both languages quite fluently, seem ready to provide any information and assistance to the assembled refugees. However, a group of Afghans who neither speak nor understand any of the two languages practically have no one to ask for help. Standing back to back in a tight group, they seem to be strangers among strangers. Navid Kermani addresses them in his native Persian. They liven up and reply in Pashto, grateful that at least someone understands and can communicate with them. They immediately gather around him with attentive expressions on the faces and carefully listen to all of his explanations, recommendations, and advice.

Whatever we kept hearing about the Afghans does not in the least correspond to the impression that we gathered in direct contact with them. To us they seemed kind, quiet and somewhat confused, mainly characterized by visible poverty. For them, it appears, it is much harder to cope with new, unfamiliar circumstances then for the noticeably much more cosmopolitan and undoubtedly richer Syrians. We learn from the people in this group that they came here from remote rural regions of Afghanistan. Apparently they are completely out of money.

It is perhaps even more important that they are also without any information about their current whereabouts and where they should go next. With the kind help of Info-park activists, Navid Kermani purchases ten bus tickets for Šid. In deep gratitude, Afghan refugees place their right hand in the middle of their chest and then gather around to quietly agree amongst themselves who out of twenty plus people from their group will get to continue further and who will have to wait for another chance. It is all done very quickly and it seems that none of those who were not selected does not in the least mind others on this sudden stroke of luck.

Once we wave goodbye to this part of their group, we are also ready to continue with our journey. We are feeling impatient and restless as if the highway is persistently pushing us forward and only forward. But just as we are about to leave the park, our attention is attracted by the pathetic human figure curled up on the pale-pink UNHCR mat, its' head completely covered so that only two dirty and disturbingly white feet are sticking out of it. It is, as we soon discover, a very young man. While he watches us from underneath, still half asleep, his frightened eyes are bleary and his dirt covered face furrowed by sticky tears.

It is virtually impossible to exchange any comprehensive information with him. Clearly he is in delirium and fever and needs urgent medical help.

None of the refugees around, however, know anything about him and he does not seem to belong to any of the groups that gather in different parts of the park. Nevertheless, many of them are approaching him anxiously to address him in various languages in an effort to find out who he is and where he is coming from.

Someone hands him a bottle of water, another a box of biscuits. He gratefully accepts both and just clings to them, his eyes still filled with fear and incomprehension. He tries to say something but cannot. Medical help is already on its way when one of the girls working in the Info-park finally recognizes him. It turns out that he is a young Roma, just one of many homeless persons who hopelessly vegetate in this shabby but lively area near the Belgrade bus and railway stations. Refugees nevertheless smile at him sympathetically while the medics already provide him with first aid. After all, in that moment he needs it at least as much as them, if not more.

Before we manage to finally continue further, we receive yet another proof that in such miserable situations the warmth and generosity of many people can and indeed will be endless. On the very edge of the park we encounter a pregnant beggar who is trying to obtain some food from several Syrian families that gathered with children at the benches near-by. Women wearing head-scarves are observing the beggar compassionately for a while. Then they quickly collect wafers, several apples and a carton of fruit juice that they themselves received from humanitarian aid. They put all items in a plastic bag and hand to the beggar this simple and hastily prepared lunch packet spiced with incomprehensible but gentle words of comfort.

When we finally leave the park, deep within us we feel the strong pulse of sparkling belief in the overpowering goodness of Humankind.

8. Epilogue: border-crossing Berkasovo-Bapska (01/10/2015, 19:00 h)

At the very end of several days of our journey we are once again travelling towards Šid. The situation on the field changes literally from day to day so that we simply cannot resist the urge to once again go to the place from which we started this journey, now impregnated with numerous impressions. Our plan is to visit the scene that we have encountered a week earlier on that narrow patch of Pannonian soil in-between Serbia and Croatia.

However, just before entering the town of Šid we catch up with a bus that drives refugees all the way from Preševo to another border crossing with Croatia - Berkasovo-Bapska. And so we quickly decide to change our plan and follow it. It is a few minutes before seven PM and the night quickly descends onto the plain. Even though we are only a short drive away from the border, once we get there, the darkness seems complete and non-penetrable.

In the unlit area along the bumpy road, we perceive the tents containing the usual combination of humanitarian and medical assistance offered to refugees on each of the checkpoints and positions we have visited so far. RED CROSS, UNHCR, HCIT, WAHA - these are just some of the international organizations that, here at the border with Croatia, provide the migrants with everything they could possibly need before they continue with their journey. We then quietly follow a group of about sixty men, women and children as they, with supplied rations and water bottles in their hand, approach a ramp.

In front of it stands a simple cardboard box with an inscription in thick blue felt-tip pen: "CROATIA - 250 M".

They all stop right there, as if on command. For a while, everyone stares straight ahead without a word, as if trying to catch a glimpse of what is awaiting them there, on the other side. But nothing seems to be visible, nothing indeed, except the blackest darkness. So they turn their heads and look back as if to use the opportunity and in one all-encompassing view summarize the entire path they have traveled up to this point so far from home.

But it's no use either - behind them there also spreads only an endless range of impenetrable darkness. Then they clench their teeth and fix their luggage determinedly on their backs, they fasten their bags upon their tireless shoulders, they lift their suitcases with their strong arms, they raise their children piggyback or accept their outstretched, hopeful hands in theirs and only then they continue on, armed with a sense of the indestructible, blind hope - Prometheus' deceitful gift to Humankind.

We stay behind watching them for a long time as they courageously, quietly and step by step, exactly as refugees have been roaming across the planet Earth since times immemorial, disappear in the darkness towards the next stage of their long and uncertain journey along the Highway to personal happiness.

This article was first published on the website of our office in Belgrade.