Industrial, corporate-driven food systems have failed to deliver food security for everyone. And they will not be able to do so in the future either. That is because food systems severely harm both nature and the people on whom they depend. Many agribusiness firms claim that they can "fight hunger" simply by producing more food. But that is far too simplistic and misleading.

Historically, industrial agriculture has delivered large increases in production for major crops. Between 1961 and 2001, regional per-capita food production doubled in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, and in South Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. It did so largely on the back of high-yielding irrigated crop varieties grown in highly specialized monocultures, boosted with lots of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. These developments have lifted many farmers out of poverty and paved the way for better diets. Per person and per day, we produce more calories than ever before. But this achievement also masks major problems.

The key question is: How can the living conditions of the poorest be improved?

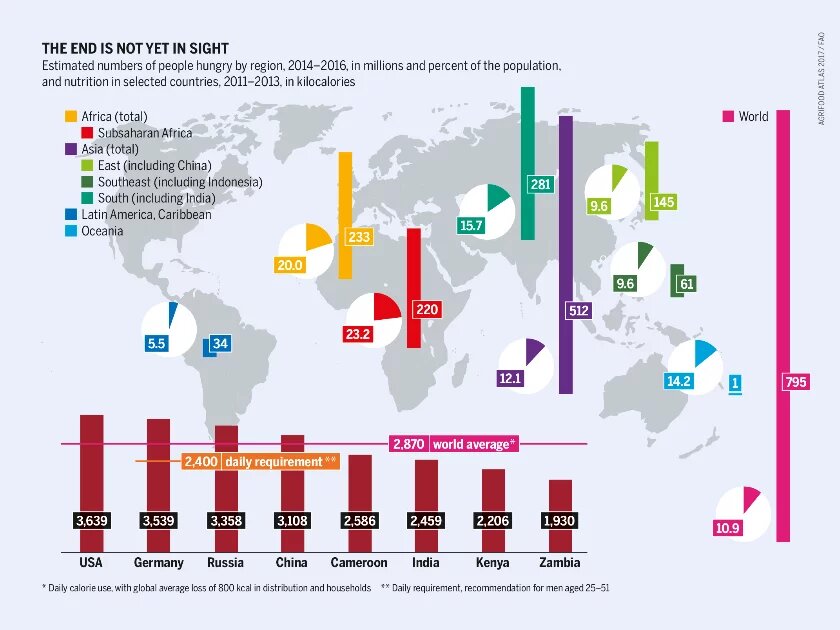

First, hunger has not disappeared. In 2017, there are still 815 million people who are undernourished around the world. A large part of the problem is related to the uneven distribution of food, which is in turn tied to poverty and social exclusion. Industrial food systems have tended to exacerbate inequalities rather than resolving them. Independent food producers – mostly smallholders – and farm workers account for more than half of those who go hungry today. Industrial agriculture is not helping them, and in many places it is making them even poorer – by depriving them of markets, expropriating their land and water, and polluting their soil. The key question is not, therefore, how to boost output. The discussion should instead focus on how to improve the living conditions of the poorest, including through agriculture, to ensure they have access to income and adequate nutrition.

Second, because the efforts have concentrated on increasing supply, little has been done to improve efficiency. An enormous waste of calories is the result. The global harvest of edible crops is today equal to around 4,600 kcal per person per day. But only around 2,000 kcal per person are actually available for consumption. A net loss of 600 kcal occurs after harvest, for example through spoilage and storage losses. Another 800 kcal are lost in the distribution system and in households. Even more – 1,200 kcal – are fed to livestock.

The Stockholm International Water Institute published these figures in 2008. Updating them and adding in the effect of fuel crops would demonstrate even greater inefficiencies. So while the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations says that 60 percent more food will be needed by 2050 to satisfy demand, it would be better to work out a plan for a fairer distribution of the supply.

Industrial agriculture handicaps the ability of current food systems to feed the world because it overexploits the ecosystem; it is a significant cause of land degradation. More than 20 percent of agricultural land worldwide is now classified as degraded, with degradation progressing at an alarming rate of 12 million hectares a year, equivalent to the total agricultural land of the Philippines.

The vicious circle of increasing pesticide use and increasing resistance

In addition, intensive pesticide use brings major risks for long-term productivity: pests, weeds, viruses, fungi and bacteria are adapting to chemical pest management faster than ever. Farmers intensify the use of chemicals in order to maintain their production levels. Often this means recourse to additional chemicals. The vicious circle of increasing pesticide use and increasing resistance brings mounting costs for farmers, as well as further environmental damage.

These impacts have already taken their toll on agricultural productivity. In recent decades, yield increases for key crops in industrial cropping systems have started to plateau in various regions of the world; for instance, for maize in Kansas or rice in Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island. A meta-analysis of yield developments around the world from 1961 to 2008 found that in around one-third of the areas growing maize, rice, wheat and soybeans, yields either failed to improve, stagnated after initial gains, or even fell.

Industrial agriculture cannot feed the world

The business model of the agrochemical companies and industrial agriculture plays an important part in these trends. The problems occur because the system relies on specialized producers and uniform products, leading to dependence on chemical inputs. For every increase in productivity achieved on this basis, there is a price to be paid sooner or later, somewhere or other, directly or indirectly, either by those who practise industrial agriculture or by others who are affected by its fallout.

Industrial agriculture also harms the environment through high greenhouse emissions and lower biodiversity, both of which further undermine future food production. If we widen the lens to socio-economic sustainability, the impacts of industrial agriculture are equally problematic. Food systems are failing food producers themselves. Many small farmers and farm workers, especially women, struggle to grow enough to eat or a surplus to sell. They lack access to credit, technical support and markets – and face volatile prices for what they grow and buy. Industrial agriculture can sustain neither the environment nor producer livelihoods. It cannot feed the world. Changes in rice production in many parts of the world show that agroecology offers an alternative: diversified farming systems that produce high yields without damaging the environment and are in tune with the social systems in which they are embedded.

» You can download the entire Agrifood Atlas here.