The pre-colonial human presence in the Amazon proves that there is no contradiction between preserving the forest and human presence. However, regional arrangements of villages and communities have been threatened by the imposition of cities that also threaten the forest.

Following the publication of archaeological discoveries accumulated over the last three decades, there is now a consensus on the existence of a low-density, agrarian, and tropical urbanization that predated colonization in the Amazon. Many Indigenous peoples coexisted and communicated by means of the rivers, from the mouth of the Amazon River to the Andes. Rivers were the primary means of transportation, and their floodplains provided abundant food, such as fish, chelonians, and fruits. The narratives of European travelers make it clear that watercourses guided the positioning of human settlements.

Settlement and forests are not fundamentally incompatible

Rivers, villages, farms, and forests complemented one another in shaping a landscape that was both molded by human activity and, in turn, influenced human generations. The village was the space for socialization and domestic life, while the river and forest served as production areas, supporting gathering, agroforestry cultivation, and fishing. From this perspective, it becomes easier to grasp that urbanization and forests are not necessarily contradictory – especially when the forest itself is produced by human interaction and serves as the primary provider of their essential resources.

Before Portuguese colonization, human settlements were small, located short distances from one another, and connected by rivers and land routes. The largest settlements were positioned at the confluence of two rivers, strategically placed for territorial control. The maintenance of this legacy today can be attributed to the incorporation of Indigenous villages into religious missions. Although religious leaders altered the layout of these settlements – introducing land allotments, for example – they preserved their original locations. In the 18th century, the Pombaline government [the government of Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, the Marquês de Pombal] expelled the missionaries but upheld the territorial organization inherited from forest-dwelling peoples. By adopting urbanization as a colonization strategy, the Pombaline administration established towns and cities on the sites of former missions, replacing Indigenous place names with Portuguese ones.

Although religious leaders altered the layout of these settlements – introducing land allotments, for example – they preserved their original locations.

Although the colonizers aimed to promote large-scale plantations, they ultimately relied on the extraction of ready-made forest products. For centuries, colonizers learned from Indigenous peoples how to collect and consume these resources. The commercial value of certain forest products justified the description of economic cycles based on their export to Europe. This trade, in turn, provided the means to develop infrastructure and equipment similar to those of industrial cities, despite their different social formation and environmental context. The so-called economic cycles came to represent cycles of exploitation and export of natural resources. For instance, the prosperity of the rubber cycle enabled the importation of sanitation solutions, energy supply, road paving, transportation infrastructure, and the private subdivision of land.

In the 20th century, Brazilian colonization led to widespread deforestation, increasingly redefining the forest as a rural space. The goal was to explore and accumulate public lands, even though they were already inhabited by people who had been stripped of their humanity by racism. The transformation of the forest into a rural area – driven by agrarian reform and major development works – displaced native populations to the outskirts of cities. This reinforced the perception of the city as the embodiment of urbanization, the space where new urban planning techniques should be applied.

A glimpse of this change occurred when large projects were supported by company towns – self-sufficient infrastructure hubs designed to house the most skilled workforce – while improvised settlements built by workers over three decades evolved into mid-sized cities.

Raw material producers gain power over habitats

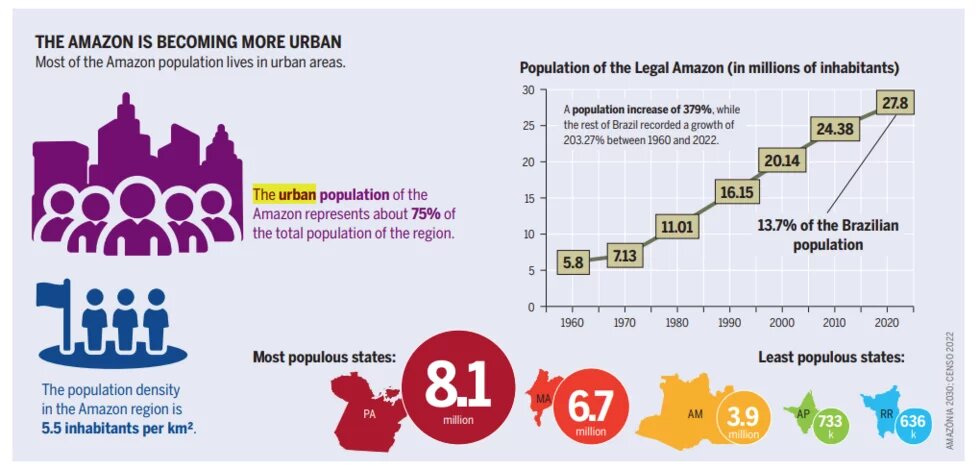

Although the majority of the Amazonian population now lives in cities, the percentage of rural inhabitants is typically twice the national average, due to the legal classification of villages and communities as rural settlements. The cities of Manaus and Macapá (in the states of Amazonas and Amapá, respectively) concentrate 60% of their states’ populations, whereas Belém, the capital of the State of Pará, concentrates 30%, experiencing population loss to its metropolitan surroundings. In this metropolis, 2022 data indicate a population increase on the islands, areas structured around villages, and communities. In Manaus, the Indigenous population is growing, and in cities such as Santarém, conflicts between native interests and commodity producers reveal that the same groups control both urban transformation and changes in so-called rural spaces. Nevertheless, along the channels of the large rivers, villages and communities preserve the legacy of pre-colonial urbanization while continuing to supply cities with food.

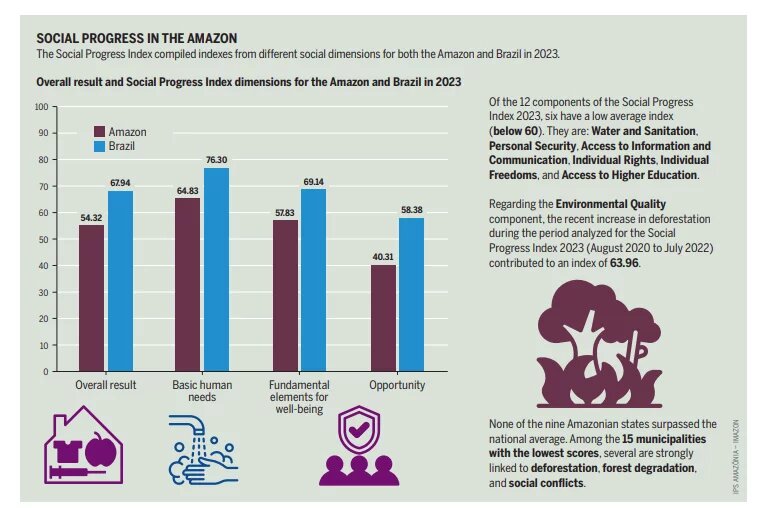

These areas complement urban centers, forming micro networks that require mobility solutions and service provisions just as much as urban areas do. In this sense, the Amazon is characterized by dispersed regional formations that allow for the existence of green interstices, which act as microclimate regulators and providers of ecosystem services and food. However, due to a lack of understanding, these formations are being dismantled and replaced by cities that are losing vegetation cover both internally and externally. Extensive occupation is the most beneficial practice for the market. However, it degrades ecosystems by incorporating native territories and dispossessing communities of their means of production, in addition to driving them into poverty. At the same time, these populations are gradually permitted to fill in floodplains, enabling high-cost macro-drainage systems to make these areas commercially viable. As a result, resilience and adaptability to contemporary crises – particularly climate crises – are being lost.

The article was first published in the Brazilian Amazon Atlas:

Brazilian Amazon Atlas | Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Rio de Janeiro | Brasil

See the Portuguese Atlas version here: Atlas da Amazônia Brasileira | Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Rio de Janeiro | Brasil