The Global South faces a deepening debt crisis, including odious debts that stifle the policy space and divert funds from essential services. A just and sustainable solution is crucial, and use of IMF drawing rights by Western countries during the COVID-19 pandemic offers a pathway.

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, the governments of Europe and the US overseeing the companies that had developed corona vaccines made a clear determination: the intellectual property enabling the development of new and innovative vaccines that could significantly decrease the risk of mortality from a corona infection could not be shared with the Global South. Rather than open-sourcing the vaccines or sharing their surplus production, Western countries hoarded doses, many of which expired unused. The resulting uproar led to the establishment of the COVAX facility through which vaccine doses - far fewer than ended up expiring and being thrown away across the EU, the US and Canada - were shared with so-called least developed countries. Just like COVID-19, so does the increasing severity of the debt crisis in the Global South require containment, before an infectious dynamic creates further damage, causing weakening economies to topple each other like dominoes.

The link between corona and the debt crisis is not just metaphorical. Coupled with delayed and limited vaccine access, the pandemic created immense fiscal pressures. The rising debt burden negatively impacts the resilience of health systems, economies, and overall capacity to respond to external shocks. Reeling from reduced tax revenues due to lockdowns, African nations simultaneously faced unavoidable public health expenditures. The Russia-Ukraine War compounded this shock, with its effects still felt today. These compounding crises have exacerbated debt burdens across the continent.

Rising debt burden: Stark, unjust realities

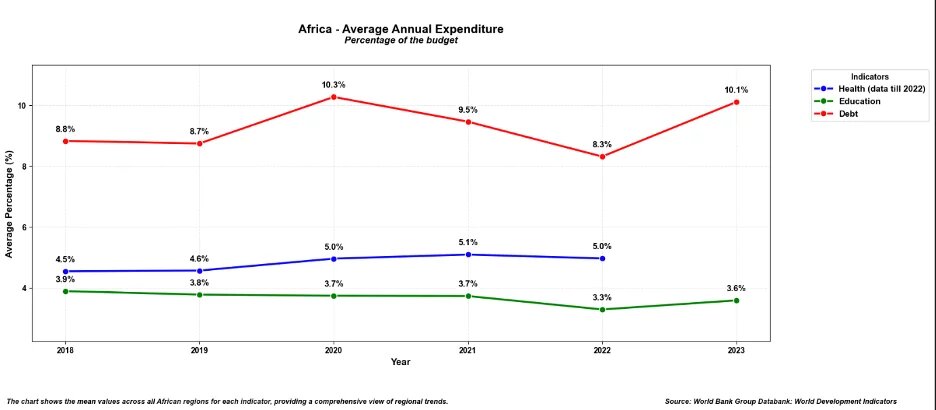

The number of countries where debt spending is higher than spending on health, education or social services is rising, as is the number of countries where spending on debt exceeds the combined budgets for two of these three core state spending obligations. It is instructive to visualise the extent to which this spending gap is growing on the African continent.

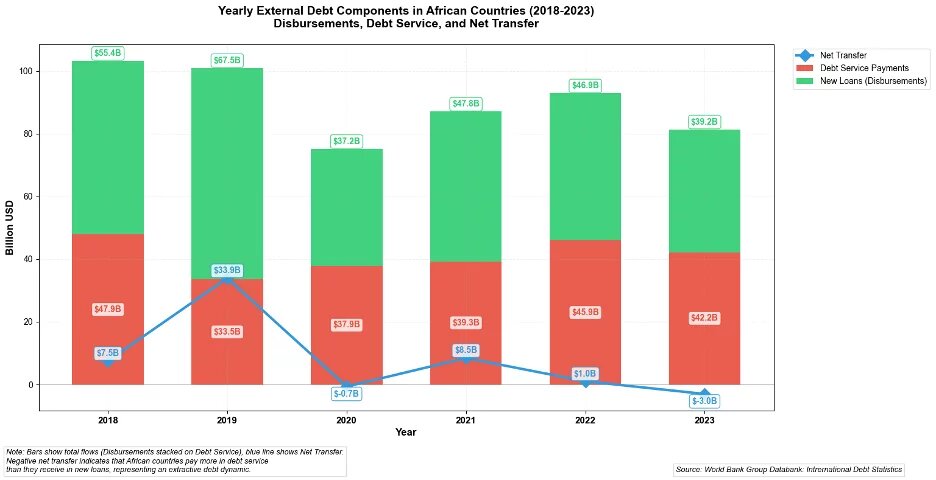

The recent sharp rise in debt service in relation to health and education expenditure illustrates a growing gap, with debt service spending being as much as or higher than health and education expenditure combined.

In 2023, the most recent year for which comprehensive World Bank data is available, African countries paid more in debt service than they received in new loans - indicating that debt service has entered an extractive dynamic. Read together with the data on African governments spending more on debt service than on education and health, this establishes the stark, unjust realities caused by mounting burdens of debt service. One kind of debt stands out as particularly egregious.

Paying their oppressors’ debt: Odious debt

Across Africa and the Global South, countries are paying off odious debts, that is, debts incurred by their former oppressors. The doctrine of odious debt posits that debt incurred without consent or democratic legitimisation by the affected population and/or without benefit to the affected population, or in cases where the creditor was aware of one or both of the above being the case, should be considered odious. It posits that sovereign debt which meets these criteria should not be transferable to a successor government. Later, scholars added the requirement that debts from loans made in breach of international law should automatically classified as odious.

The case of South Africa provides a stark example of odious debt. The liberated, democratic South Africa, under Nelson Mandela, chose to accept and repay debt incurred during the apartheid era. With a £11.3 billion debt burden in 1996, South Africa paid £2.3 billion in interest and repayments. Estimates suggest this money could have funded healthcare for the entire population, built 300,000 new homes, and still left funds for schools.

Beyond South Africa itself, Southern Africa was also greatly impacted by the apartheid regime’s campaign of war and destabilisation, which forced the governments of Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Angola into costly proxy wars - resulting in odious debt as well. Other examples of extractive regimes that created odious debt include the Abacha regime of Nigeria and the Mobutu regime of Zaïre, now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The odious beyond the obvious

Odious debt incurred decades ago has observable ramifications today, as the cases of Southern Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria make abundantly clear. However, odious debt also brings some of the structural issues of the current debt regime to the fore; despite repeated calls to declare apartheid-era debt odious, the South African government has accepted to pay the debt and repudiated repeated requests from within the country to change course. As a rationale, the government has asserted that some of the very banks implicated in the odious debt were actually the same institutions that the current democratic government was pursuing for investments. In addition, the risk of being downgraded by rating agencies, which would increase the cost of borrowing, has been cited. This illustrates the importance of reforming the international financial system to tackle both odious debt and the financial governance architecture that co-creates unsustainable debt burdens. This requires reassessing the role of the IMF and the World Bank.

Colonial continuities of Bretton Woods institutions

The Bretton Woods institutions share a colonial legacy; it is not a coincidence that they arose in a post-war context that was marked by huge transfers from the colonies to the metropoles that helped stabilize the economies of the Western allies, notably including during the post-war reconstruction era. They were built atop of an extractive colonial economic system in which colonies were expected to finance the oppressive, coercive and extractive policies inflicted on them by generating surpluses through extraction.

Power imbalances within the membership of the IMF and the World Bank allow countries with the most influence and shares to determine the organizations’ policies and payouts. This became apparent once more in 2021, when the financial strain on budgets caused by the pandemic motivated IMF members to pursue an allocation of their shares in the IMF – their special drawing rights (SDR). The US, Canada and European countries – which hold the largest share of drawing rights in the IMF – were able to use them to receive 70 per cent of the 650 billion dollar emission without taking on new debt or credit.

This same mechanism needs to be unlocked to transcend the cycle of debt – beginning with odious debt but expanding it to unsustainable debt. As Europe finds itself increasingly marginalized in a more transactional world of big power players, such a move would provide credibility to forge the new partnerships it needs to act on the global stage.

Ties that unbind: From odious creditors to partners in reconstruction

The historical record and the SDR payout mechanism described above demonstrate both the necessity and a pathway to addressing the debt crisis more fundamentally, justly, and sustainably. The 2021 SDR allocation shows that this can be achieved without straining European budgets. If Europe is serious about forging new relationships with the Global South, as key European representatives have repeatedly suggested (see e.g. German foreign minister Wadephul’s 2025 UN general assembly speech), the debt crisis presents an opportunity. The ongoing global realignment is reshaping the geopolitical landscape, offering the EU a chance to adopt the emerging AU Common African Position on Debt (CAP). African countries are consolidating their positions, with key aspects already clear; they advocate for SDR allocations to facilitate debt relief and for a reformulation of the SDR quota system to increase their payout beyond the 5 per cent received in 2021. SDR allocations should be rechannelled to the African Development Bank Group (AfDB) as a designated holding institution for regional and national priorities.

Another key pillar in the AU’s CAP is the establishment of an African Rating Agency for unbiased assessment of countries’ creditworthiness. Europe should indeed support this, having recently accredited its own European rating agency, German-based Scope Ratings, to address the prior monopoly of US-based agencies. These shared experiences that have given rise to the EU accrediting a new agency with regional expertise and the AU demanding the same for Africa could actually provide the ties that unbind from biases in the status quo of the rating agency architecture and its key role in determining the cost of debt.

Constructive first steps such as these would offer opportunities to forge a new relationship in a shifting geopolitical reality. Just as the Global South cannot afford odious and unsustainable debts, the West, particularly Europe, can no longer afford to be – or to abet – odious creditors.

The views and analyses expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Heinrich Böll Foundation.