Domestic violence and hegemonic masuclinity are deeply entwined in China – they reinforce and stabilize each other, to the detriment of women. Our author pleads for an alternative thinking about masculinity in general – drawn from pre-modern concepts and Bruce Lee.

Pretext

“Have you stopped beating your wife?” is a classic example in Linguistics or Logics textbooks to show how a loaded question looks. I found it funny when I read it in my master’s program. Only years later did I realize how dark this humor is.

Domestic Violence and Hegemonic Masculinity

Apparently, the wife-beating phenomenon was taken for granted so much that the presumption – the interlocutor is known to have been beating his wife non-stop for a certain amount of time – could appear in classrooms unproblematically. In the West, it was not until the 1970s that the term “wife-battering” was coined to recognize the abnormality of such behavior. Afterwards, feminists more prominently used “domestic violence” to bring a private issue into public discourse. In China, the Marriage Law in 1950 had prohibited “the abuse and abandonment of women”, but it was not until the 1990s, during the NGO-ization of feminism, that “domestic violence” was translated into Mandarin. In 2015, domestic violence became illegal with the issuing of the Anti-Domestic Violence Law.

In China, the Marriage Law in 1950 had prohibited “the abuse and abandonment of women”, but it was not until the 1990s, during the NGO-ization of feminism, that “domestic violence” was translated into Mandarin.

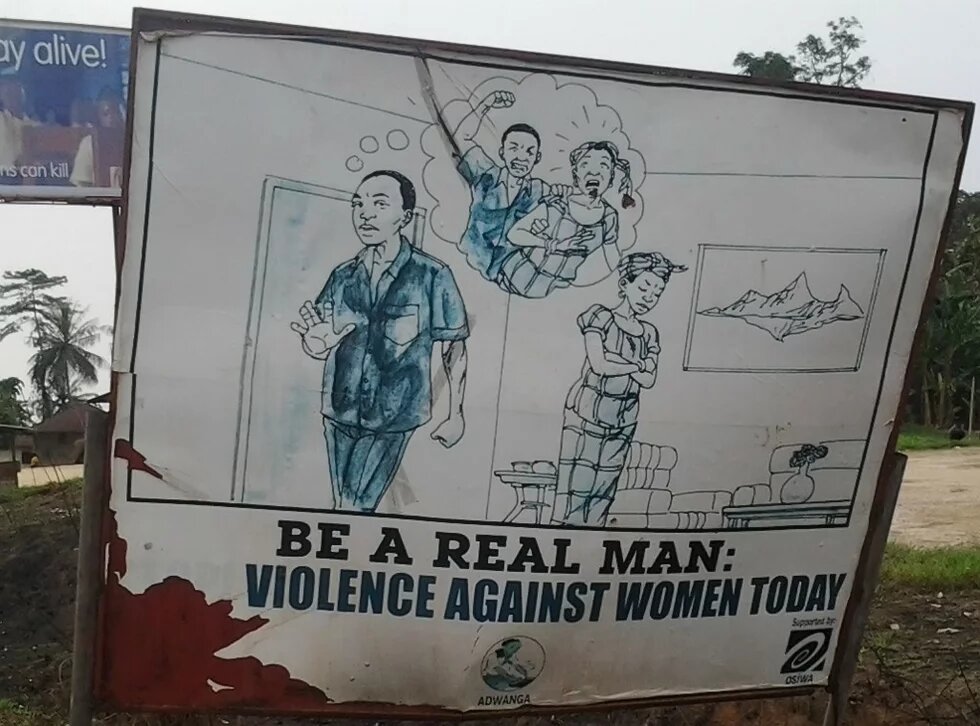

Regarding the mechanisms behind domestic violence, “masculinity” provides a key clue. In the social world, “masculinity” answers “what is an ideal man?” and describes the roles, behaviors and attributes expected from a male person. According to R.W. Connell, “hegemonic masculinity” sets the standard against which other forms of masculinity (and femininity) are judged, often marginalizing men who don’t conform and reinforcing male superiority. In many societies, traits such as control, strength, dominance over others (especially women) form a core part of this ideal. Domestic violence, particularly against women, can be both a product and a tool of hegemonic masculinity. Men who adhere to or feel pressured to perform this dominant form of masculinity may use violence to assert power, maintain control, or respond to perceived threats to their authority within intimate relationships. The maintenance of the hegemony, however, could also be in the form of anti-violence campaigns.

The Cans and Cant's of the Law

Since the passage of the Anti-Domestic-Violence-Law, explicit progress has been made. As one of the most fundamental infrastructures, the issue of the Protection Order – an order issued by the court upon the application by the victim to protect them from potential harm, such as domestic violence or stalking – has been increasing annually: from 680 in 2016 to 5596 in 2024. Nevertheless, considering the frequency of domestic violence, it is hard to be optimistic. According to the Third Survey on Social Status of Women in China (2010), 25% of married women had encountered different kinds of domestic violence (physical and verbal insult, financial control, forced sex); in 2016, the Status Quo of Domestic Violence indicates a rise to 30%. Strangely enough, in the Fourth Survey on Social Status of Women (2021), a comparable data is missing.

Moreover, the implementation of Law meets multiple structural problems. Wei Ping (“For Equality”), one of the organizations for women’s empowerment, published a monitoring report in 2025 that lists six barriers: the imbalance in the capacity of different agencies in different regions, especially the frontliners; campaigns against domestic violence are monotonous and sporadic; the lack of transparency in information and statistics; the insecurity of funding; the precarious operation of women’s shelters; “social force” is limited.

Men will be men?

Although many of these issues seem to be institutional, behind the institutions are human beings entrusted with the capacity to do justice to victims. However, in reading cases in the report, I am bewildered by the absurdity.

In one case, Ms. Chen filed for divorce on the grounds of having suffered from multiple domestic abuse throughout her 20-year marriage to Mr. Li and was denied by the primary court, because “Chen failed to provide sufficient evidence that the marital relationship had broken down … Considering also that Mr. Li is opposed to the divorce”. Discontent, she then filed an appeal with an intermediate court. Right before the second hearing, Mr. Li, agitated by Chen’s insistence on divorce, put Chen on his shoulder and rushed out of the courtroom, with his “wife” screaming in fright. The judge and police stopped him and “criticized” him. In the end, after the compulsory judicial mediation, Chen agreed to “give Li another chance”. What was eventually fulfilled was Li’s original wish of not divorcing.

Although many of these issues seem to be institutional, behind the institutions are human beings entrusted with the capacity to do justice to victims.

The reason for the denial of Chen’s first request, the indulgence of the judge towards Li’s open despise before the Court, as well as Chen’s final forgiveness for Li’s abuse, make one wonder, why everything in the end works to the favor of a person with violent behaviors, disrespect to law and extreme emotional instability?

We can only speculate, that even the judges, although supposedly with an interest in justice, do not live in a void free from androcentric conventions according to which “men will be men”. And this applies beyond Court. In the “twin” studies on the Law’s implementation, focusing on police officers, a team found that legislation, organizational support and training have not directly translated into punitive actions from the police. One of the variables is their attitudes towards gender roles: officers who endorse that male family members shall have more dominant place compared to female ones showed a higher level of tolerance for Intimate Partner Violence”.

Hegemonic masculinity and the tolerance of it must be unlearned. The question is, could there be alternative “learning materials” than “Have you stopped beating your wife”?

Inspiration from pre-modern China

The delegitimation of alternative forms of masculinity is partially how hegemony is maintained. Consequently, reimagining masculinities is a necessary step to resistance, thus also a step to rein back domestic violence. However, alternatives are not offered. We need to construct it ourselves.

That patriarchy comes in different forms has long been suggested by feminist scholars. According to Kam Louie, China has long established its own system of masculinities, which was distorted by the Western model after the colonization in early 20th century.

In the first comprehensive analysis of Chinese masculinity, he proposed the Wén - Wǔ dyad to understand masculinity of Chinese men across different periods. Unlike in the West, where masculinity and femininity come in a dichotomy, in China, masculinity is defined in relation not to women, but to men – women were excluded from the system of power and signification.

While 文 (wén) refers to a scholarly disposition of cultural attainment, reflecting sentiments, reason and civility, 武 (wǔ) points to the military temperament of martial valor, relating to bravery and strength. In general, Wén is valued more than Wǔ, but both are commendable. Most importantly, a mix of both is always deemed the most respectable.

Unlike in the West, where masculinity and femininity come in a dichotomy, in China, masculinity is defined in relation not to women, but to men – women were excluded from the system of power and signification.

Interestingly, Wén figures could appear effeminate. A typical wén man is Jia Baoyu, the main character in the 18th century Qing dynasty novel Dream of the Red Chamber, who exhibits the extreme sentimentality to the universe, the profound attachment to nature, and the admiration and even jealousy of women. Yet in traditional China, Baoyu was not deemed as less of a man. Typical wǔ traits are found in the heroes of the Chinese Ming dynasty novel Water Margin, which tells the story of 108 men gathering and rebelling against the government. One of them, Wu Song, of immense strength, is depicted to have bare-handedly beaten a man-eating tiger to death.

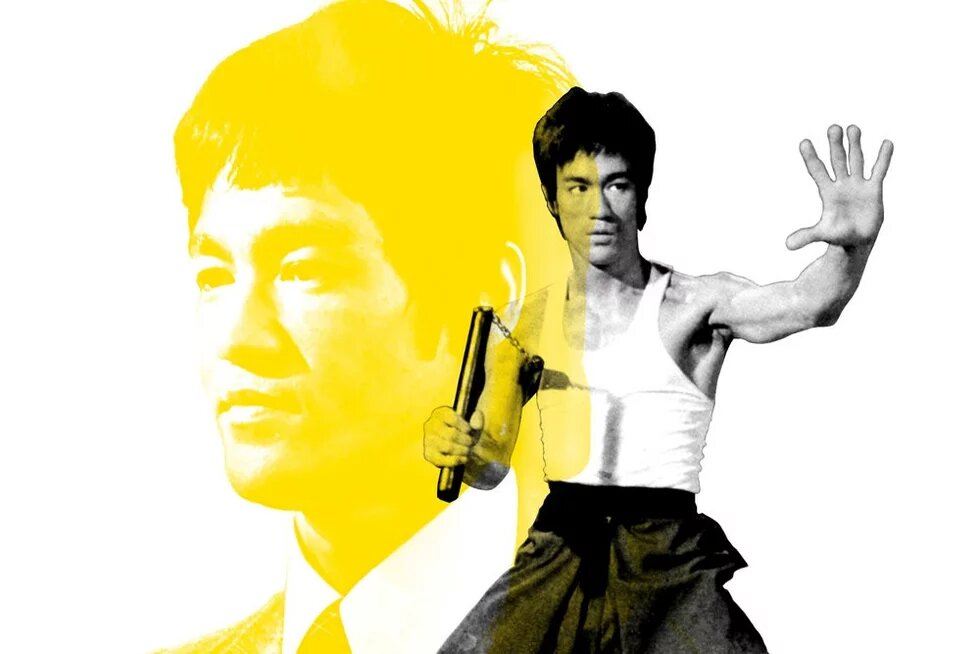

Both are praised, yet exhibiting only one side, neither would be reckoned as superior. To Western readers, perhaps the most familiar figure carrying both is Bruce Lee in real life.

Many know Bruce through kung fu films and remember him as a martial artist, thus a typical Wǔ figure, but it is less known that he studied philosophy at university and was influenced by Taoism and Buddhism which underlied his fighting philosophy. Moreover, he was also versed in poetry. In the collection Bruce Lee: Letters of the Dragon, a poem titled Who Am I? reveals his reflection on his own masculinity.

Who am I?

Am I a giant among men,

Master of all I survey,

Or an ineffectual pygmy

Who clumsily blocks his way?

Am I the self-assured gentleman

With a winning style,

The natural born leader

Who makes friends instantly,

Or the frightened heart

Tiptoeing among strangers,

Who, behind a frozen smile, trembles

Like a little boy lost in a dark forest?

Most of us yearn to be one,

But fear we are the other.

Decisive and accurate in his kicking, yet sensitive and vulnerable in his writing, Bruce Lee seems like a master of pens and fists, or Wén and Wǔ (文武双全).

Ending Remark

How can we imagine an alternative to hegemonic masculinity from the above account? Can Wén and Wǔ be stripped off from the dominant dynamic that they were born in?

At the end of his monograph, Louie acutely sensed that Wén and Wǔ have gained their trans-gender, trans-class, and even trans-cultural life in today’s world. Moreover, Song Geng suggests the resemblance of traditional Chinese masculinity to what radical feminists imagine as androgynous, which is in consistence with many western health promotion programs. Finally, the discourse of Wén – Wǔ is more accessible as an advocative resource in China. “文武双全” has already become idioms to encourage citizens to be both civilly polite, respectful and physically healthy and acute. This sounds more effective than importing gender discourse from the West.

Therefore, the Wén – Wǔ discourse seems to hold a seed for what Connell called “positive hegemony” – a version of masculinity open to equality to women, which is a key strategy for contemporary reforms. With the Anti-Domestic-Violence-Law as well as the ascending grassroots feminism, this dyad sounds like a promising addition to the current anti-domestic violence efforts.