According to its mission statement, Trafó House of Contemporary Arts in Budapest is a receptive venue unique to Hungary, embedded in the international contemporary scene, where various genres – theatre, dance, new circus, music and other visual arts – are presented in an individual and authentic manner. An Interview with Managing Director György Szabó.

Mr Szabó, what is TRAFÓ for you?

It is my child, as I founded it myself in 1998. It is an educational centre in which I try to let people discover the world and find their own answers in it. He who was born blind only knows the colour black. Yet even in order to interpret what black is, you need to see the colour white too.

Is TRAFÓ a theatre?

Well, formally yes. This is what the city of Budapest wanted, despite my original idea of creating an innovative arts centre. Innovation does not like such fixed frameworks.

The performances we host come from a very broad range of genres. In the beginning, we mainly solicited contemporary dance productions. Then somehow contemporary dance became so popular in Budapest and internationally too that we had to think of different forms of performing arts – such as theatre and circus – always on the move and open to new ideas and interdisciplinary solutions.

Where would you place TRAFÓ within the Hungarian theatre world?

Outside of it, due to its innovative nature. Thinking of the independent arts world, TRAFÓ is the “kindergarten” of creative artists, a place for playing, renewing and experimenting; state theatre is the adult world then.

Considering the financial difficulties which are especially tangible in the cultural sphere, how can you manage TRAFÓ?

We do get state funding, so we are in a better situation than the independent theatres, as we know the budget we can count on each year. Our goal is to make the most of this public money – to give the floor to Hungarian creative artists and to inspire Hungarian audiences with international performances.

The cultural industry has been turned completely upside down; the supply is way larger than the demand, which, of course, obliges our management style to change all the time. Thanks to dancer-choreographer Pál Frenák and his company, we launched an introductory programme for schools in 2002. Since then, we have been communicating constantly with our audience, making family members of them.

How does current Hungarian politics influence TRAFÓ’s daily work?

We do not host any explicitly political events; however, politics is a part of everything. There are some artists, such as Árpád Schilling from Krétakör, who are extremely direct, such as in their piece Loser, which visitors to the Contemporary Drama Festival can watch in its recorded version. Generally, the independent theatre scene is more outspoken than the traditional state theatre world, although recently the latter has become blunter too.

There is no censorship in Hungarian culture. Cultural politics has subtler methods to decide what should flourish and what should slowly die out. How paranoid the government in power is can be measured by whether they see an enemy in artistic performances which do reach a certain part of society.

What is the current funding system like?

The corporate tax support system known in Hungarian as “TAO” was introduced at the end of the previous decade by the social democratic government. This means that companies, instead of paying their taxes to the state, can pay a certain amount to cultural institutions. Theatres can thus receive a grant based on audience size and ticket prices – up to 80% of their ticket-based income. This grant was intended to be an extra source of financial support in addition to the state subsidy; however, starting in 2011 the current government reduced state support by the amount of TAO the institutions receive. Moreover, they included sports in the possible areas of corporate tax support, which many companies find more attractive than supporting cultural institutions. Consequently, it has become even more difficult for the latter to find financial resources.

How do you see the future of experimental theatres in the light of this?

TAO pushes the system towards commercialisation: using clichés which attract audiences and going for small productions. Since funding is based on audience size and ticket prices, independent as well as state or municipal theatre productions want to know for sure that they will attract audiences; it encourages market-oriented thinking.

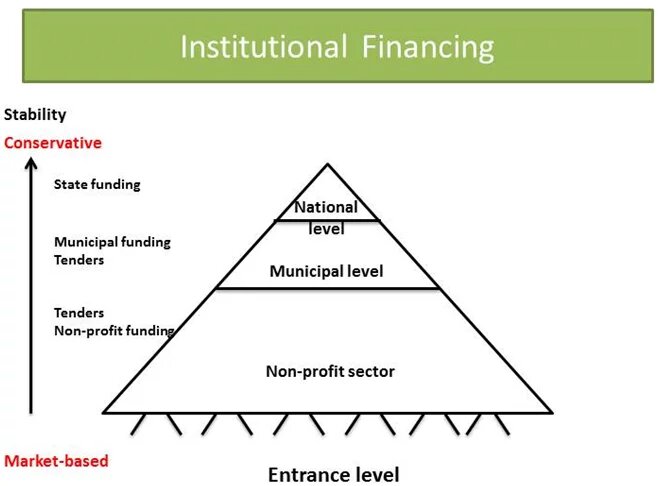

One needs to be highly determined about one’s artistic ideas and participate in international networks and co-operations to find funding for quality art. Krétakör and Workshop Foundation are such models, for example, which have managed to create something out of nothing. The problem is that these small initiatives coming from the non-profit sector are not encouraged by our current cultural funding system to step up to higher levels – to municipal and state funding. As a result, critical, independent voices are seriously discouraged in the end.