Since 2010 Fidesz has managed to win all parliamentary by-elections leading up to a resounding victory of Viktor Orbán at the parliamentary elections in April 2014 and easily won municipal elections in October 2014. Recently things have changed dramatically.

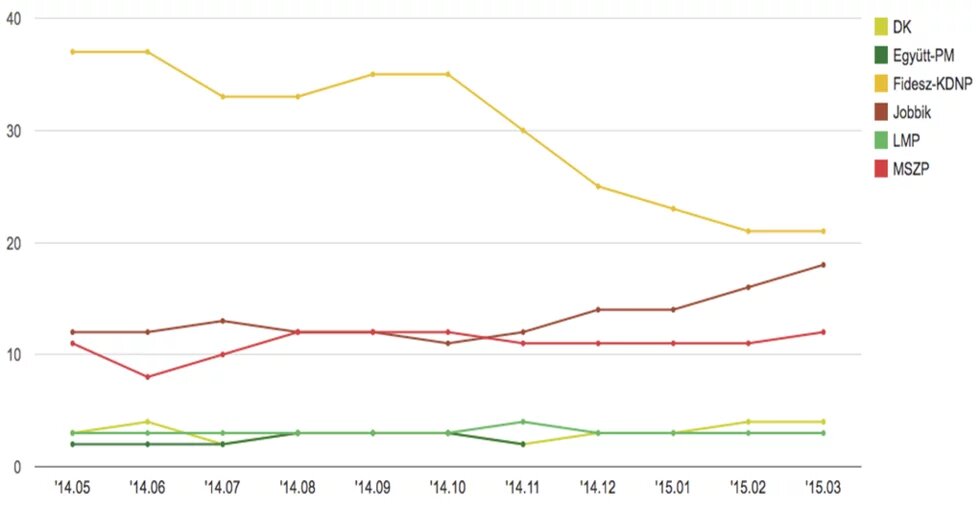

Since November 2014, the right-wing governing party has lost three critical by-elections and has seen its popularity drop from 35 to 25 percent. While such a decline in popularity is not without precedent (see Figure 1), defeat at critical elections is a new experience for Fidesz. Between 2010 and 2014, when the whole institutional system and the tax regime were overhauled, Fidesz managed to win all three parliamentary by-elections organised during the period. Crucially, Viktor Orbán also led his party to a resounding victory at the parliamentary elections in April 2014, and Fidesz easily won the municipal elections in October 2014. Things have changed dramatically since then, however.

In November 2014, the Socialist candidate easily beat his right-wing rival at the by-election organised in Budapest’s Újpest district after the death of the incumbent Socialist MP. Analysts had already noted at the time that Fidesz’s formidable vote-maximising machine appeared to have faltered, but this was attributed to local specificities (e.g. the Socialist Party’s historical embeddedness in this working-class neighbourhood). This assessment had to be revisited, however, after Fidesz’s shock defeat in one of its bastions – the town of Veszprém – at a by-election organised in February 2015 (after the incumbent Fidesz MP was chosen to become Hungary’s next European Commissioner).

The victory of the independent candidate supported by left-wing parties was primarily newsworthy because it stripped Fidesz of its parliamentary supermajority. Analysts, however, were mainly shocked by the scale of the defeat: the Fidesz candidate trailed the winner by 9 percentage points in a traditionally right-leaning district. If we are to believe the accounts of Fidesz activists, many of the party’s core voters who had hitherto exhibited unflinching loyalty, opted to stay at home despite exhortations to vote in order to prevent a left-wing victory. The latest debacle, at the by-election organised on 12 April in nearby Tapolca, confirms that this was not merely a local trend.

The difference in the number of votes received by the candidates standing in the by-election and those who stood for election in the same district in April 2014 reveals that a disproportionate number of Fidesz supporters chose to stay home (18,750 voters had cast their ballots for Jenő Lasztovicza in April 2014, while only 10,093 supported Zoltán Fenyvesi at the by-election). As in Veszprém, Fidesz lost a district where its candidate had won by close to a 20-point margin last spring. Neither the prime minister’s personal appearance in Tapolca, nor hundreds of paid Fidesz activists were able to cajole supporters into making their way to the voting booths. The historic victory by the far-right candidate – who gave Jobbik its first direct mandate – was therefore facilitated by Fidesz’s inability to mobilise its numerically superior support base. As one commentator put it, “A well-organised but soulless army was routed by a highly motivated guerrilla group.”

It would be an understatement to call this anything less than a dramatic development. Without the unwavering loyalty of 1.5 million citizens, Viktor Orbán would not have won a two-thirds majority at the parliamentary elections in April 2014. This is because the new electoral regime – adopted by the Fidesz supermajority in 2011 – disproportionately rewards the strongest party. Orbán’s thinly veiled plan to remain in power for two decades ultimately relies on his ability to keep the opposition divided and demobilised, and his fan base united and active. While in the past there has not been a flicker of doubt as to whether these two key conditions would be met, the results of the last three by-elections have raised the possibility – if not the probability – of a Fidesz defeat in 2018. In what follows, I will first analyse the problems plaguing Fidesz, a party which has garnered renown around Europe for its formidable campaign tactics and mobilisation potential. I will then go on to evaluate the predicament of the opposition and to assess in particular whether Jobbik – the only party that has benefited from the rift between Fidesz and popular constituencies – could become Fidesz’s main rival in 2018.

Fidesz as plebeian party: a crumbling myth

Orbán understood as early as 2008 that the fate of the upcoming parliamentary election would hinge on a numerically large portion of the electorate, who – despite feeling alienated from mainstream politics – still took part in the electoral process because they possessed important assets which they did not wish to lose. In order to mount a successful comeback after two unsuccessful parliamentary elections, Orbán reached out to blue-collar workers and small entrepreneurs. Building a coalition with the lower middle class was no easy task for Fidesz, however. Infamously, the party’s then-vice-president, László Kövér, had talked about the Socialist Party’s powerful sway over “block-house prols”.

His comments struck a sensitive chord, hitting the hundreds of thousands of low-income families where it hurt the most: their sense of pride and self-esteem. Luckily for Fidesz, the political alliance between popular constituencies and the Socialists quickly disintegrated amid the global financial and economic crisis. Ferenc Gyurcsány’s government planned to introduce a host of painful austerity measures with a view to balancing the budget. These policies constituted a U-turn on his predecessor’s pledge to bring about “welfare change” one decade following “regime change”, and Orbán seized on this crisis of trust by calling a “social referendum” against the planned introduction of tuition fees in higher education and fees for hospital visits. The government lost the referendum by a wide margin and collapsed a few months later.

In the course of the 2010-2014 parliamentary cycle, Orbán attempted to strike a fine balance between serving the interests of Fidesz’s erstwhile core supporters – the propertied bourgeoisie – and its newfound popular support base. The government’s flagship economic policy – the introduction of a flat income tax – clearly benefited higher income groups and left Fidesz vulnerable to attacks from the Socialist Party and Jobbik, who both vied to present themselves as the defenders of low-income groups.

This goes a long way towards explaining Fidesz’s drop in popularity in 2011 and the party’s inability to attract popular constituencies until the beginning of 2013, when chief strategist Árpád Habony unveiled the secret weapon of utility price cuts. There is a consensus among analysts that this policy initiative contributed decisively to Fidesz’s second two-thirds victory in 2014. However, political developments in the last six months have eroded Fidesz’s carefully crafted image as a plebeian party. It is useful to briefly review the key events that created such a corrosive force.

Problems emerged in the immediate aftermath of the municipal elections in October 2014. On 16 October, a pro-government daily (Napi Gazdaság) reported that the U.S. government had introduced a visa ban on Hungarian tax officials. The paper suggested that the most likely explanation for the ban was that the American government wanted to signal its deep disapproval of investigations launched by the Tax Authority (NAV) against American companies operating in the Hungarian agro-industrial sector.

The story’s publication forced the U.S. embassy to provide an explanation of its own, namely that the visa ban was imposed on six officials (including members of the government) whom the U.S. suspected of involvement in corruption. Both the newly reorganised Foreign Ministry and the Prime Minister’s Office were unprepared for this unusually direct form of criticism from one of Hungary’s key allies, and despite its best efforts the government was unable to refute suspicions that some of its high-ranking members were indeed guilty of corrupt practices. This hurt Fidesz and undermined the prime minister’s image as a leader capable of curbing the appetites of his subordinates.

Orbán had previously managed to avoid having to wage simultaneous struggles on both the domestic and foreign policy fronts, but his famous political nose had led him astray this time. On 21 October, in the midst of the NAV scandal, news emerged that the government was planning to tax internet use. Although the levy was substantial in its own right (0.5 EUR per gigabyte), the fact that Fidesz was borrowing a tool from Putin’s toolkit cast a dark shadow over the proposal, powerfully suggesting that Orbán had been serious about moving closer to illiberal rule.

Five days later, an unprecedented number of citizens poured onto the streets of Budapest to demonstrate against the government. In the last days of October, demonstrations were held in towns that generally see very little political activity outside election periods: Szombathely, Eger and Békéscsaba. Leading Fidesz politicians were not only alarmed by the size and geographical scope of the demonstrations, but also by the type of people participating in the rallies: polls revealed that a significant proportion of those present were Fidesz supporters.

Orbán paid a heavy price for his media war

Pressured by his base, the prime minister quickly decided to scrap the internet tax. While this decisive move put an end to the wave of demonstrations, further confidence-building measures would have been necessary to reassure supporters and to quell discontent within the ranks of the governing party. Investigative journalists examining internal conflicts and divisions had signalled that the relationship between the prime minister and Lajos Simicska, Fidesz’s former treasurer and the head of the country’s most powerful business lobby, had deteriorated significantly after Fidesz’s victory in April 2014. Simicska controlled key positions in the state apparatus, and the rumour was that Orbán wanted to use his second mandate to curb Simicska’s influence. These allegations received indirect confirmation in November 2014 when Simicska announced that he was contemplating a run in the Veszprém by-election.

With hindsight, it is clear that at this point Orbán still could have prevented a falling out with the second most powerful man in Fidesz, affording himself room to reassure disgruntled supporters. Instead of heeding calls for “consolidation”, however, Orbán picked up the gauntlet that Simicska had thrown down and called in his troops to do battle with the tycoon. At stake in this war – which will likely go down in Hungarian political history as the period of the “second media war” – is control of key positions in the telecommunications sector.

Orbán’s initial plan was to increase his influence over RTL Klub (owned by the Bertelsmann group) and to force Simicska to relinquish control over his own media empire (comprised of a TV station, a daily, a weekly, and two radio stations). In exchange for greater influence over of the media landscape, Orbán appears to have offered a long-term guarantee of profitability, hoping that this would be enough to persuade both players. This was a miscalculation, however. Instead of bowing under the pressure, RTL responded by striking key Fidesz leaders where it hurt the most: by reporting on the dubious personal finances of key ministers and the Orbán family. As for Simicska, he responded with an attack on Orbán’s charisma by publically calling him “geci” and claiming that Orbán had reported on him to the Communist authorities during their military service together in the 1980s.

The prime minister paid a heavy price for his media war, which turned Simicska’s right-wing media empire against the government, creating confusion within Fidesz’s support base. This contributed greatly to the Fidesz losses in the Veszprém and Tapolca by-elections along with the loss of its parliamentary supermajority. Although Orbán has enough money and time to build a brand new media empire, it is doubtful whether he will be able to reclaim the hundreds of thousands of supporters who have now joined the camp of disillusioned unaffiliated voters or the rival right-wing party, Jobbik. If Simicska is skilful, he will continue to spur division and disorientation on the political right or even contribute to the emergence of a new centre-right narrative upon which a new party could be built in future.

While the war with Simicska threatens to sow divisions within the right-wing camp, it has not harmed the prime minister’s carefully crafted image as a man seeking to work for the benefit of average Hungarians. Nevertheless, the scandals surrounding the personal finances of Fidesz’s top leaders and the NAV affair have cast a dark shadow over Orbán’s pledge to govern not only in the name of but also for the benefit of the people. The cumulative effect of these separate wars of manoeuvre has been to erode Fidesz’s image as a plebeian party and Orbán’s personal image as a leader capable of bringing mutually antagonistic forces in line with the national interest. Considering the degree to which his personal reputation has been soiled, we have good reason to believe that Orbán will not be able to cast himself into the role of the father figure which he (following Putin and Erdoğan) has dreamt of becoming.

A significant new development: voters adapt to the new electoral system

It would, of course, be premature to surmise that Orbán’s demise is imminent. The next election is three years from now and the prime minister continues to hold key cards: a lot of money, total control of the state apparatus, and powerful influence over his remaining supporters. It is also important to keep in mind that Fidesz managed to rebound after a similarly troubling dip in popularity in 2013.

Nonetheless, it is clear that a large number (up to one-third) of Fidesz’s core supporters have lost their faith in the party and/or have joined the ranks of the opposition. This spells trouble, but the majoritarian element of the new electoral regime (notably, the first past-the-post rule introduced in the 106 electoral districts where the majority of parliamentary mandates are distributed) could still ensure a Fidesz victory if the governing party retains a lead over rivals and the opposition remains split between supporters of left-wing parties and Jobbik.

The latest by-elections have shown that opposition parties, especially Jobbik, have not only caught up with but surpassed Fidesz in terms of mobilisation potential. As was revealed in Tapolca, this can tilt the balance of forces towards the opposition even in electoral districts where Fidesz has more supporters than its rivals do. The real headache for Fidesz, however, is the fact that members of the opposition are beginning to change their behaviour as a way of adapting to an electoral regime that was designed to benefit Fidesz. Supporters of the Socialist Party and Jobbik have recently demonstrated an unprecedented degree of willingness to unite behind the strongest opposition candidate with a view to defeating the governing party. The municipal elections in October 2014 provided the clearest indication of this new trend, but the results of the Veszprém and Tapolca by-elections offer additional confirmation that tactical voting has taken place. This spells trouble for Fidesz, because there are many electoral districts where support for Jobbik and the Socialist Party together exceeds support for the governing party and where one of the two opposition forces clearly enjoys an advantage over the other.

It is still very much an open question as to how the opposition parties will respond to such a situation. The electoral regime which preceded the one that was unilaterally adopted by Fidesz in 2011 provided an opportunity for political parties to weigh their forces in a first electoral round and to bargain with potential partners (e.g. by offering to withdraw candidates in one district in exchange for a reciprocal move by the partner in another district) before the second round of elections. If this regime was still in place, it could allow for some form of cooperation between Fidesz and the Socialist Party against Jobbik, much in the same way that France’s Socialist Party and Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) have supported each other’s candidates to keep the National Front at bay. In fact, under the previous system Fidesz would have had two weeks to try to reverse the Jobbik tide and bridge the 300 votes separating it from Jobbik in the Tapolca by-election by convincing Socialist supporters to back its candidate.

Such a strategy is not an option under the new electoral regime, however, which is comprised of only one electoral round. Under the current rules, the dominant forces of the left and the right – the Socialists and Fidesz – would have to agree on the mutual withdrawal of candidates before the elections. This is not a highly realistic option. Fidesz deliberately created the new electoral regime to avoid having to cooperate with rivals. Moreover, cooperation with the Socialists is also impossible because right-wing politicians have blamed them for most of the banes plaguing Hungary. If Fidesz still had a two-thirds parliamentary majority, it could unilaterally tinker with the electoral system to its own benefit, but since its defeat in Veszprém Fidesz no longer possesses a supermajority in parliament.

In the light of these considerations, it is possible that the Socialist Party and Jobbik will concentrate their energies on winnable districts and tacitly abandon other seats which they stand little chance of taking, thereby indirectly supporting the bid of their main rival against Fidesz (in practice this could involve the Socialists abandoning supporters in predominantly rural districts – where Jobbik could beat Fidesz – and Jobbik abandoning supporters in larger cities – where the Socialists could beat Fidesz). If the balance of forces does not change substantially by 2018 – and this is big “if” – such competitive cooperation could result in a hung parliament where Fidesz would have to cooperate with either Jobbik or the left to pass legislation.

While historically entrenched differences in geographical embeddedness between the centre-left and the far-right favour the stabilisation of a three-tier political system, popularity trends revealed by opinion polls point to the possibility (if not the probability) of Jobbik emerging as Fidesz’s main rival in 2018. Figure 1 provides a clear indication that Jobbik is the only party that was able to capitalise on Fidesz’s decline in popularity, and that the balance of forces between the centre-left and the far-right is shifting towards Jobbik. In the remainder of this article, I will attempt to explain why Jobbik has been the main beneficiary of the troubles plaguing Fidesz.

The chances of Jobbik emerging as Fidesz’s main challenger in 2018

Fidesz’s strategy of ruling over a divided opposition was based on the premise that Jobbik would remain in quasi-quarantine. Right-wing strategists believed that Jobbik would continue to be perceived by a majority of voters as a party indelibly tainted by racism and led by radicals who cannot be trusted with the reins of power. This was not merely a miscalculation as it turns out, but a case of self-delusion as well. While Jobbik has greatly benefited from the mistakes of the Fidesz government and the powerlessness of the left-wing opposition, Fidesz also bears direct responsibility for the rise of the far-right. Instead of opting for a strategy of containment based on a clarification of the differences separating the right from the far-right, Fidesz’s leaders chose to adopt Jobbik’s key policies (e.g. utility price cuts, conversion of foreign currency loans, granting citizenship to Hungarians living outside the country’s borders, an Eastern opening towards Russia and Turkey, etc.) in hopes that this would weaken the far-right party.

Thus, in order to preserve their hegemony, they were willing to displace Fidesz’s centre of gravity to the right. This calculation was not wholly unfounded; indeed, the skilful manipulation of public opinion through the right-wing media in the run-up to the last two parliamentary elections allowed Fidesz to substantially weaken Jobbik. This strategy had a side effect, however, the severity of which became apparent only after Fidesz’s nosedive. By adopting Jobbik’s key policies, Fidesz undermined the boundary between the moderate and far-right lifeworlds, thereby destroying the walls of the quarantine that had constrained Jobbik’s ability to grow. Had Fidesz policed the boundary that separated it from the far-right, it may have limited Jobbik’s rise and perhaps prevented a far-right victory in Tapolca.

In order to reach out to new – mostly middle-class – constituencies, Jobbik obviously had to do its own homework.

One of the most surprising lessons of the last year is the swiftness with which party leader Gábor Vona managed to implement the same de-stigmatisation strategy that France’s National Front has been pursuing for years now under Marine Le Pen’s leadership. Vona has so far managed to strike a delicate balance between distancing himself from the party’s extremist past and keeping the party’s core hard-line supporters within his camp. His successful bid to hold the increasingly heterogeneous far-right camp together was greatly helped by the spread of anti-Fidesz sentiment and persistent negative feelings vis-à-vis the Socialist Party. Yet while anti-establishment sentiment and the convergence between the two mainstream parties have clearly expanded Jobbik’s manoeuvring room, it would be wrong to attribute the party’s rise solely to these factors.

My own research into the tactics developed by Jobbik to build a bastion in a town not far from Tapolca revealed that Jobbik has invested a great amount of thought and effort into building bridges with local communities and creating a network of motivated activists and donors who can be mobilised to support local campaigns. On the ideological level, the national leadership’s key achievement was understanding that they had to stress Jobbik’s ability to take up the baton from Fidesz by presenting itself as a clean ultranationalist force determined to implement Viktor Orbán’s unfulfilled promise to bring about “real regime change”. Jobbik used the symbolic capital it acquired during the course of its conversion from an extremist to an ultranationalist party to attract local opinion-leaders, and subsequently relied on these legitimisers to expand its local networks and to build local party chapters in areas which had previously been off-limits for the party. This painstaking local work boosted Jobbik’s image as a plebeian party seeking to bring prosperity to a countryside abandoned by elites. Jobbik’s grassroots approach further differentiated the party from its mainstream rivals – especially Fidesz, whose leaders had taken on an arrogant tone which had undermined the party’s newly acquired plebeian image.

I find it important to stress that Jobbik’s ongoing conversion to a mainstream political force poses a danger not only to Fidesz, but in equal measure to the centre-left. The quasi-quarantine in which Jobbik was trapped until 2014 limited movement between the Jobbik and Socialist support bases (this can be explained through the logic of stigmatisation, which reinforces symbolic boundaries and in-group identity). The de-stigmatisation of the far-right may now allow for a swing from the left to the far-right because the most powerful bond linking the left and its voters – namely, anti-fascism – has been powerfully undermined by the erasure of the fascist stigma. Jobbik’s resounding victories in municipal elections in former left-wing bastions such as Ózd and Devecser have shown that such a swing is no longer simply a theoretical possibility.

The most likely scenario

It would be premature to bury the Socialist Party, of course, or to rule out the possibility of a new credible force emerging on the left, but the chances of a left-wing renewal appear bleak at the moment. In the run-up to the parliamentary elections in April 2014, commentators were primarily concerned with dissecting the rivalry between the forces that constituted the Alliance formed by the Socialist Party, the Democratic Coalition and the Together-PM alliance. Fragmentation, however, is not the main problem faced by the left, in my view. The main obstacles, as I see them, are a lack of credibility and an aching lack of ideas about what the left stands for and what it has to offer. The dominant force of this electoral coalition – the Socialist Party – is most significantly affected by an acute shortage of creativity and credibility. Between 2010 and 2014, the party did not table a single proposal that voters would have remembered when entering the voting booths in April 2014. Although former party leader Attila Mesterházy distanced himself from the Blairite heritage of the Gyurcsány years, he did not spell out in any clear way what he would actually do were he to become the next prime minister. Although his successor, József Tóbiás, appears to be more serious about working out new ideas and proposals, the persistent presence of unpopular leaders undermines the credibility of efforts to renew the party from the bottom up.

Due to a lack of space, I will not provide an overview of the other left-of-centre forces here. Suffice to say that these actors are also hindered by serious difficulties. The Democratic Coalition is hampered by Party President Ferenc Gyurcsány’s persistent unpopularity. The two newly founded parties – Together and PM – enjoy a much higher degree of credibility, but their lack of resources undermines attempts to extend their influence beyond the capital city. The green party (LMP) is severely limited by a political strategy that rules out any cooperation with the left, and therefore undermines the party’s ability to reach out to disillusioned left-wing voters who make up a sizable chunk of the wavering electorate. As for the politically unaffiliated activists who have organised most of the demonstrations against the government during the last twelve months, their lack of vision and strategy prevents them from building an organisation and sustaining their momentum.

Taking all of the above into consideration, it is plausible to claim that Jobbik is much better positioned than its left-wing rivals to mount a serious challenge to Fidesz. If it manages to defend its image as a clean plebeian party and if the centre-left cannot extricate itself from its current hibernation, there is a good chance that Jobbik will manage to attract a sizable number of voters who previously supported the left. In this case, the Hungarian political system would move towards the same bipolar structure that first emerged at the end of 1930s, when the Social Democratic Party lost its rural voters to the Arrow Cross Party, allowing the latter to challenge the rule of the authoritarian nationalist right-wing regime. I am not suggesting that this is the most plausible scenario, but it can no longer be ruled out.

The alternative, in the absence of any sign of renewal on the left, is for Fidesz to rebuild the electoral alliance that allowed it to win two consecutive parliamentary elections. This time, however, it will certainly require substantially more than a secret weapon to remedy the breach of trust between Fidesz and its heterogeneous and now fragmented voter base. What is required is nothing less than a shift in political strategy involving: some degree of consolidation, that is, an end to the symbolic war against internal enemies; material reassurances for low-income groups without placing a heavy burden on economic growth or the middle class; and a clear demarcation from Jobbik, most notably with regard to foreign policy and social policy.

Based on Viktor Orbán’s governmental record, it is highly doubtful that he is willing (or able) to implement such a decisive break with his earlier strategy. Since his departure from the helm of his party is also inconceivable at the moment, the most likely scenario is that the prime minister will attempt to check Jobbik’s rise without radically changing his strategy. What we are therefore likely to see is an orchestrated character assassination attempt, whereby Fidesz will strive to portray Jobbik as an extremist force that has only changed its appearance, and as a party that is financed by Russia. On my estimation, the odds of this strategy succeeding are no better than fifty percent. First, it is doubtful whether negative propaganda will be able to overpower Jobbik’s grassroots efforts, most notably its positive record in municipal governance. Second, Fidesz is not in the best position to criticise Jobbik’s connections to Russia.

After all, Orbán is the one who recently welcomed Vladimir Putin in Budapest in order to sign a major deal on building two nuclear reactors in Paks. Finally, it is difficult to run a negative campaign from the position of a governing force. There is always the well-founded suspicion that negative campaigns are only designed to conceal governmental failures – an assumption that does not appear to be unfounded in our case. Nonetheless, there is a chance that Orbán will manage to weaken Jobbik and perhaps even to sow divisions within the ranks of the far-right party by fuelling an internal power struggle between radicals and moderates. If, in the meantime, he provides a bit of breathing space for the left, this may just be enough to reinstate the balance of power between the far-right and the left-wing opposition. Were Orbán to manage such a political stunt and pull his regime back from the brink, he is certain to go down in history as one of the most ingenious tacticians of the last hundred years. If he fails, he is likely to be blamed for helping history repeat itself by opening the door to the far-right.