The subject of LGBT rights is gaining more and more attention in Tunisia.The number of homophobic statements is reaching record highs, and people continue to be arrested for sodomy. Thanks to the commitment of non-governmental organizations the issue is now being widely discussed in the public and the media.

Although taboo before the Revolution of 2011, the issue is now discussed in public and in the media, largely because of the organizations that openly support the cause. At the same time, the number of homophobic statements is reaching record highs, and people continue to be arrested for sodomy.

The past year was marked by many convictions based on Article 230 of the Tunisian Penal Code that criminalizes homosexual relations. The case of Marwen* and that of six students from Kairouan were widely reported – both in Tunisia and abroad.

In its statement of 29 March 2016, the international human rights organization Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported the testimonies of five of the young men who had been traumatized by their arrests.

Arbitrary convictions and police violence

In September 2015, a young student, Marwen, was arrested during a murder investigation in Sousse. Once suspicions of homicide had been eliminated, the interrogation quickly shifted to the defendant’s sexual orientation and he was accused of having had homosexual relations with the victim.

According to HRW, the boy claimed that police officers subjected him to physical violence and humiliating treatment. They allegedly slapped and threatened him: “We’re going to rape and brutalize you and make you sit on a glass Fanta bottle.” Faced with these threats, Marwen confessed that he had occasionally gone out with the deceased.

The young man was then brought to the hospital for a rectal examination, which he agreed to undergo, hoping to prove his innocence. He described the test as “very difficult”.

On 22 September, Marwen was sentenced to one year in prison, based on Article 230 of the Penal Code, which prohibits sodomy. He was imprisoned until 17 December, when the Sousse Court of Appeal reduced his sentence to two months’ imprisonment (already served) and a fine of 300 dinars.

On 4 December 2015, six students were arrested in their dormitory in the city of Kairouan. They claimed that officers at the police station hit and insulted them, calling them “miboun”, a degrading term for “gay” in the Tunisian dialect. After spending the night in detention, they were brought to the hospital, where they were forced to undergo anal tests, which they bluntly refused. As in Marwen’s case, the test was supposed to prove their “homosexual behaviour”.

“I felt as if they were raping me. I still feel that,” says Amar*, one of the students.

On 10 December, they were sentenced to the maximum term of three years in prison and banished from Kairouan. They were incarcerated for one month before the sentences were reduced to one month (already served) and a fine.

All six students recount having been abused by the guards and other prisoners. Two of the six, Amar and Kais*, told HRW that they were subjected to physical attacks, humiliating treatment and rape every day.

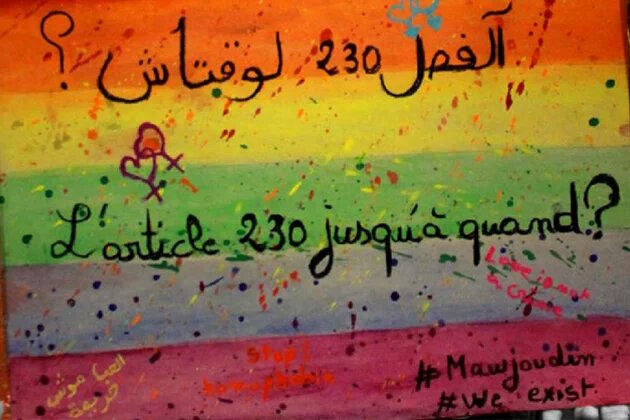

A poster for the campaign to abolish Article 230 of the Penal Code.“The guards forced us to dance like women for them until they got bored. If we refused, they slapped us. They made us go out in handcuffs every day, hit us and rammed their billy clubs into us.”

Support from the organizations and civil society

These two cases provoked a wave of indignation that was relatively new in Tunisia. In social media, members of the public criticized the arbitrary convictions, and especially the rectal examinations, as infringements of the students’ personal freedoms and international conventions. Tunisian human rights organizations such as the Tunisian League of Human Rights and the Tunisian Association of Democratic Women officially called for Article 230 to be scrapped, arguing that it contravenes the new Constitution, which is supposed to guarantee personal freedom and privacy.

Many national and international organizations called for the release of all persons detained under Article 230, the end of prosecutions based on sexual orientation and a ban on forced rectal examinations, noting that the United Nations Convention Against Torture considers the practice to be an attack on an individual’s physical integrity.

This wave of support made it possible for the two cases to get media coverage, and the sentences were reduced on appeal. But even after being released from prison, victims of Article 230 are still in a predicament. Rejected by their families and those close to them, they are often left to their own devices, and are psychologically fragile or in financially precarious situations.

The various organizations do their best to support them. Damj, for example, which officially was founded in 2011 but had already been operating during Ben Ali’s dictatorship, watches out for some 85 young people in LGBT community welcome centers where they can discuss their anxieties. The organization specifically looks out for people who are in precarious situations because of their sexual orientation. Mawjoudin offers psychological support to victims of discrimination and physical attacks.

Other groups choose to participate in the public debate. Since being legalized in May 2015, Shams has received a lot of attention, particularly in the media, because it is the only organization that demands respect for the rights of sexual minorities in its founding principles. Shams created a head-on debate about homosexuality by participating in televised debates and holding public meetings.

Shams’ media visibility has, however, also worked to its disadvantage: On 12 December 2015, its vice president, Hedi Sahly, had to flee the country because of numerous death threats. On 4 January 2016, the organization was notified that the state was suspending its activity for 30 days on the grounds that it was violating the association law. Shams immediately appealed the decision.

According to Ahmed Ben Amor, another Shams vice president, the order was “political”. It was taken after MP Abdellatif Mekki of the Islamist Ennahdha Party sharply criticized the existence of an association defending homosexual rights. Mekki declared that “these (homosexual) practices are illegal” and authorizing the organization “constituted a threat to social harmony”. He also threw in random comments about the divorce rate, domestic violence and drug use.

On 24 February 2016, the Court finally ruled in favor of Shams, which was allowed to resume its activities. “Shams praised the law for taking a fair and neutral position,” declared Ahmed Ben Amor to Inkyfada. “It was normal for the court to rule in our favor because the grounds for the complaint were totally unfounded. Shams is a perfectly legal association.”

Some days later, the association – supported by many artists and activists –launched a TV commercial demanding repeal of Article 230.

A sharp increase in homophobic reactions

Opening the discussion on sexual orientation has, however, also led to more homophobic speech. On 16 March 2016, on the set of Tunisna TV, actress Aïcha Attia declared, “I am against homosexuality and its encouragement. But I am very tolerant.” Internet users pointed out how contradictory her remark was, and she became the laughing stock of social networks.

Barely a month later, actor Ahmed Landolsi made a vicious statement on the “Klem Ennes” TV program, stating that “homosexuality is a disease” that has no place in a society where Islam is the official religion. The actor’s supporters defended his freedom of speech, while LGBT sympathizers demanded that he furnish a public apology. Ahmed Landolsi refused.

The following week, Ahmed Ben Amor of Shams appeared on the same program. But, the activist lamented, what was supposed to be his right to respond to the actor’s remarks turned into a “sterile” debate full of “clichés” about homosexuals. “I was only supposed to be addressing one person. I pointed out how homophobic and misogynistic Ahmed Landolsi’s comments were and was confronted with questions like: ‘In a gay couple, who plays the woman and wears the bikini at the beach?’”

Following his television appearance, the activist received nearly 500 death threats – on the phone, in social media and even in the street.

A lack of political will

Even if the debate about LGBT rights has burst into the public sphere and media in Tunisia, few politicians comment favorably about them. One of the few reactions of note came from Mohamed Salah Ben Aïssa, then justice minister, following Marwen’s conviction. On 28 September 2015, on Shems FM, he called for repealing Article 230, which he views as contrary to the new Tunisian Constitution: “Violating personal freedoms and privacy is no longer allowed.”

The following week, his remarks were repudiated by Tunisia’s President Béji Caïd Essebsi who declared to Egyptian television that repeal of the law “will not happen” and the justice minister was “only speaking for himself”. On 20 October, the latter was booted out of office – officially because of litigation regarding the Higher Council of Magistrates.

The same story was heard within the Islamist Ennahda Party. In an interview with France 24 on 8 October 2015, its leader Rached Ghannouchi approved the president’s action and said he was “against repealing Law 230 – while respecting everyone’s personal freedom”.

Despite the debate within Tunisian society, the government does not seem to want to deal with the issue or even consider repealing Article 230, claiming that it is not a priority. Many organizations have criticized the lack of political support and the trivialization of homophobic remarks.

“The government is not reacting,” comments Ahmed Ben Amor. “When I wanted to file a complaint because of all the threats I get, the police told me that they are defending the country against terrorists – not protecting ‘faggots’. Homosexuals are simply second-class citizens in Tunisia.”

Author's note

* First names have been changed to preserve the witnesses’ anonymity. Last year, we showed that the organizations that defend LGBT rights were expressing themselves openly. Now we want to report about how the debate on the subject is evolving.