Morocco’s elections in October 2016 were a test for the democratic transition that was promised by the monarchy in the context of the 2011 upheavals. However, the national poll showed indices of undemocratic practices.

Morocco's 10th parliamentary elections were held on October 7, 2016 and were the second national poll to be organized since the adoption of the new constitution in 2011. In terms of their effective implementation and institutionalization, these elections have been perceived as providing an opportunity to put to the test the new constitutional provisions. They were more importantly viewed as a trial to the Monarchy's willingness to effectively continue on a proclaimed path of ‘democratization’.

Indeed, since the ascension to power of King Mohammed VI in 1999, different measures were undertaken to enlarge the spheres of political participation and public liberties. Elections held under his rule have been considered to be the most transparent in the history of Moroccan elections. Following the 2011 constitution, the powers of the parliament and the government were reinforced and the justice was given some independence. More spaces were created by the regime to provide ordinary citizens with channels to voice their opinions or to influence legislation and policies.

The 2016 contest is also a test to the capacity of political parties to mobilize the citizenry around their programs and to reconcile them with electoral politics. Since 2007, voter turnout has been very low. Different studies have demonstrated that political apathy and mistrust vis-à-vis politicians and political institutions are the main reasons behind abstention. In addition, a significant segment of Moroccan society in urban centers is aware of the unequal relationships of power between the ‘representatives’ of the people and a dominant monarchic institution, and is therefore reluctant to vote for a parliament where real power does not reside.

High number of nonvoters

The results of 2016 legislative elections show that abstention is becoming a persistent pattern of voting behavior with 57 percent of registered voters who turned their back to the polls. The political environment preceding the elections was that of cynicism and disenchantment with the political offer. Political party campaigning was very heated especially between the ruling Party of Justice and Development (PJD) and the Authenticity and Modernity (PAM), a party close to the palace circle and supported in various ways by the Ministry of the Interior.

Rather than a debate on programs and policies, campaigning was characterized by empty anti-Islamist slogans on the part of the PAM and personal quarrels between political leaders. Different political parties denounced the support of the Ministry of the Interior to the candidates of the PAM. This kind of behavior on the part of the state has reminded Moroccans of the days when elections were held under King's Hassan rule and orchestrated by his Minister of Interior Driss Basri.

For many, these elections constituted a step backward in the process of ensuring transparent and fair elections which initially started with the new reign. The ways in which the 2016 elections were managed contradict the spirit and principles of the 2011 constitution and constitute a threat to the ‘path of democratization’ that the monarchy claims to follow.

Elections and the Dynamics of Party Politics: A Constructed Bipolarization

The 2016 legislative elections were to fill for a five year term the 395 seats of the lower house of Morocco's bicameral legislature. Candidates from 24 political parties and coalitions run for the elections. In Morocco, the partisan landscape is largely divided. The centrality of the monarchy and its capacity of manipulation have played a fundamental role in the fragmentation and weakening of political parties. Despite this plethora of political parties, effective competition was limited to eight main political parties: the so called parties of the national movement that is the Party of Independence (PI- established in 1944), the Socialist Union of Popular Forces (USFP-1974) and the Party of Progress and Socialism (PPS-1943); pro-royalist parties: the Popular Movement (MP-1957), the National Rally of Independents (RNI-1978), the Constitutional Union (UC-1983) and the Party of Authenticity and Modernity (PAM-2008) ; finally the ruling Islamist Party of Justice and Development (PJD-1996).

Under the reign of Hassan II, alliances or splits within parties were 'made up' according to the stakes of the moment. To maintain its control of the political scene, the regime has also opted for the creation of pro-royalist parties usually referred to as "partis de l'administration". Over the years, the monarchy has managed to create a clientelist system where the safeguarding of personal interests has become a common value of the partisan elites. The inability of parties of the national movement, mainly the Istiqlal party (PI) and the National Union of Popular Forces (UNFP, later USFP), to manage their conflicts has also contributed to the fragmentation of the partisan sphere.

The long tradition of multiparty politics has not led to the rationalization of the partisan sphere nor to the establishment of a democratic culture among its elites. Indeed, power relations are based more on patronage and nepotism. Despite the recently adopted party bill, there is a trend towards the erosion rather than the union or fusion between parties. Organized around issues related to environment, liberalism and Islamism, 23 political parties were created during the past 15 years. In Morocco, the multiparty system translates a simple plurality in the number of political parties and not a plurality of ideologies, a situation that played favorably in the hand of the monarchy.

The creation of the Authenticity and Modernity Party

The recent elections in Morocco indicate that the regime continues to manage and control the partisan sphere. The creation of the Authenticity and Modernity Party (PAM) by a close friend of Mohammed VI, Fouad Ali El Himma, in 2008 was a clear sign of this kind of attitudes on the part of the regime. Initially established to limit the rising influence of the Islamist party, the PAM has inadvertently contributed to the weakening of other political parties, notably the PI, the USFP and the MP. The proximity of El Himma to the king had attracted a number of opportunist politicians to leave their own parties and join the PAM, highlighting for many Moroccans the unprincipled and clientelist nature of political parties in Morocco.

The PAM has created a political atmosphere where politics is devoid of any moral and ideological substance. In the 2015 local elections, the PAM has managed to win mainly in rural areas not because of any coherent party program or ideology but primarily as a result of the classic role that the local notabilities play in terms of bribes and attracting the votes of a segment of rural society that is typically poor, depoliticized, and uneducated. This phenomenon has remained part of the October 2016 elections.

On the other hand, the PJD, once considered by many analysts as an “outsider” and an organized opposition party, has managed to become an “insider,” and to “normalize” its presence in the Moroccan political scene. From one election to the other, the PJD was able to increase its seats both at the local and national levels. The PJD won the parliamentary 2011 elections with 107 seats, scored very high in practically all major cities in the 2015 local elections and won the majority of seats in the 2016 legislative elections (125 seats).

The 2016 electoral contest was dominated by fierce competition between the PJD and the PAM to the level that the media spoke about the polarization of the partisan scene in Morocco. It is too early to say whether these elections mark the emergence of a bipolar partisan spectrum. During electoral campaigning, the parties’ stance on issues was not clear. In general, there were no real debates about issues and problems that Moroccan society is faced with. Rather personal accusations and quarrels characterized much of the debates. Whatever political opening or reforms that took place in Morocco under Mohamed VI seem to be constantly contradicted by the political practices that are reminiscent of the autocratic nature of rule that the regime is not yet willing to detach itself from.

Electoral Participation: A Persistent Pattern of Abstention

Since the 2007 legislative elections, the discourse on the importance of electoral participation became more and more pronounced. Aware of the importance of citizens’ votes, the monarchy mobilized various political actors (the Ministry of Interior, political parties, and civil society organizations) in order to convince a large number of Moroccans to register on electoral lists and to go to the polls. The act of voting was referred to as part of “national” and “citizen’s” civic duties. To convey their messages, the Ministry of Interior and most political parties contracted with communication companies for assistance with the conception of their marketing strategies.

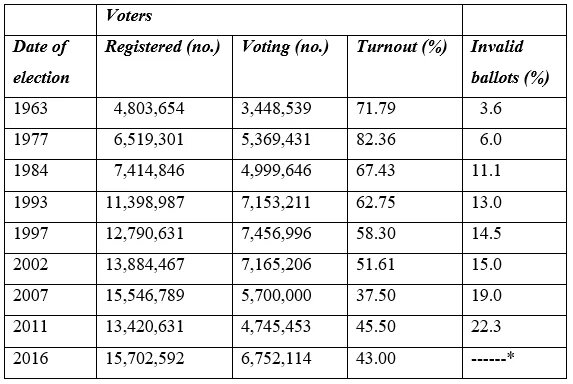

Despite these measures, it seems that Morocco’s limited political liberalization has depressed electoral participation. Since 1997, Moroccan elections have been marked by low turnout (see Table 1). The marketing of the 2007 legislative elections had a very limited impact: only 37 percent of registered voters went to the polls. Voter turnout witnessed a relative increase in the 2011 legislative elections (45.5%). However, it is important to mention that eligible voters numbered more than twenty million, thirteen million of them were registered on the electoral lists and only six million voters actually cast their ballots. With the 2016 parliamentary elections, 43% of registered voters went to the polls. Voter's turnout indicates that people's trust in the country's politicians and parties continues to be weak and that political apathy is still predominant. It is also clear that the awareness campaigns of diverse political actors had little influence on the decision to participate in the elections. Moreover, with all the efforts and the mobilization of resources by parties such as the PJD and the PAM, it still remains difficult to mobilize more Moroccans to go the polls.

Voter turnout in legislative elections since 1963

Abstention is not the only growing tendency in Moroccan electoral politics: the number of invalid ballots is also getting higher. During the 2007 legislative elections, 19 percent of voters cast blank ballots. It has increased to 22.3 percent in the 2011 parliamentary elections. While abstention reflects people’s growing awareness of a political game that no longer deserves their involvement, it seems safe to speculate that blank ballots are a form of political protest. They express mainly the disenchantment of the youth and the educated about electoral politics. Blank Ballots could also correspond to the fact that people are not familiar with the technicalities of the voting system especially the elderly and the uneducated.

Does the 2016 election matter?

Morocco is a constitutional monarchy in which the king has ultimate authority. While the regime has kept up with a seemingly democratic procedure of holding elections, it seems clear that the electoral process is regularly held under the effective control and orchestration of an undemocratic state. The 2016 contest shows that the state still intervenes in various ways to manipulate the partisan scene and the process of elections. Different political parties denounced the irregularities and state support to the PAM. Moreover, critical voices say there is no guarantee of transparency of elections that are organized under the auspices of the Ministry of Interior. Thus, the neutrality of the state and the transparency of the elections are still challenges to be dealt with. What is clear is that the Moroccan political scene continues to provide us with a peculiar context whereby techniques and procedures associated with democracy help sustain an undemocratic system of rule.

The long-term success of the PJD Islamists in the Moroccan political scene will depend first on their ability to make things change for Moroccans as far as social and economic realities are concerned. Ultimately, their success will strongly depend on their ability to carve out an independent political space vis-à-vis palace politics and the makhzen (deep state), where the power and decision making are really centered. This is unlikely to happen as the regime seems resilient in terms of introducing meaningful political changes. In this context, elections will continue to be instances to perform the democratic play in Morocco.