While political and social avenues for free speech are limited and prohibited, Cambodian visual artists find limitless forms of creative expression to critically examine many complex urban, social and environmental concerns.

Art as form of civic engagement

After a new constitution was established in 1993, Cambodia has been witnessing an unprecedented transformation in various fields for such a small country. With an influx of foreign aids and a rebuilding mission, change has been very present and has become somewhat a "normalcy" over the last three decades. Urban, social, and environmental changes have been the recurring issues for critical observations made by Cambodian contemporary artists. Many create artworks as a response because they are directly affected by these changes and/or they feel compelled to express, as the government systematically suppresses the direct avenues for free speech. This political context, in turn, productively challenges the artists to be creative and strategic in their visual language. Operating within a small yet growing circuit and community of contemporary visual art, these artists often do not claim a direct societal or political role in their artworks or of themselves. Their artworks primarily circulate through private and community art galleries and are not usually widely known to the mass Cambodian public. However, this "quiet" form of creative expression is no less civically engaged than a political one.

Khvay Samnang

For example, artist Khvay Samnang from Phnom Penh is among those who critically comment on the city development, which has been happening at a rapid pace with alarming consequences. Samnang boldly speaks on the aggressive city's practice of covering lakes with sand to construct new buildings at the cost of evicting thousands of urban poor and damaging natural ecosystems. In his performance work Untitled (2011), he visits several lakes in Phnom Penh where the sand dumping is taking place or forthcoming. He gets into the water and pours a bucket of sand over his head and half-submerged body, whereas the images in the background show houses being dismantled or flooded. Samnang's performative photographs evoke an emphatic sensory experience to the audience about the lives on and of the lakes being threatened.

Eng Rithchandaneth

While Samnang employs a direct visual critique, some other artists explore metaphor and poetry of their artistic medium. For instance, in an installation work Rooted (2019) by Eng Rithchandaneth, the artist plants grass seeds in a vacant house in a bustling Phnom Penh neighbourhood. Over two weeks, the grass expands all over the house in organic shapes, covering from the floor to the walls and to the ceiling. Daneth refers this rapid spread to the city's chaotic mushrooming of new building constructions erasing its urban history. The artist also introduces this notion of pervasiveness in urban development in her later work Colony (2020), an installation of organic forms of seemingly insect mounts occupying a whole gallery space. Observing a system of organising in an insect world, the artist also hints at the growing systemic power of the state.

Sao Sreymao

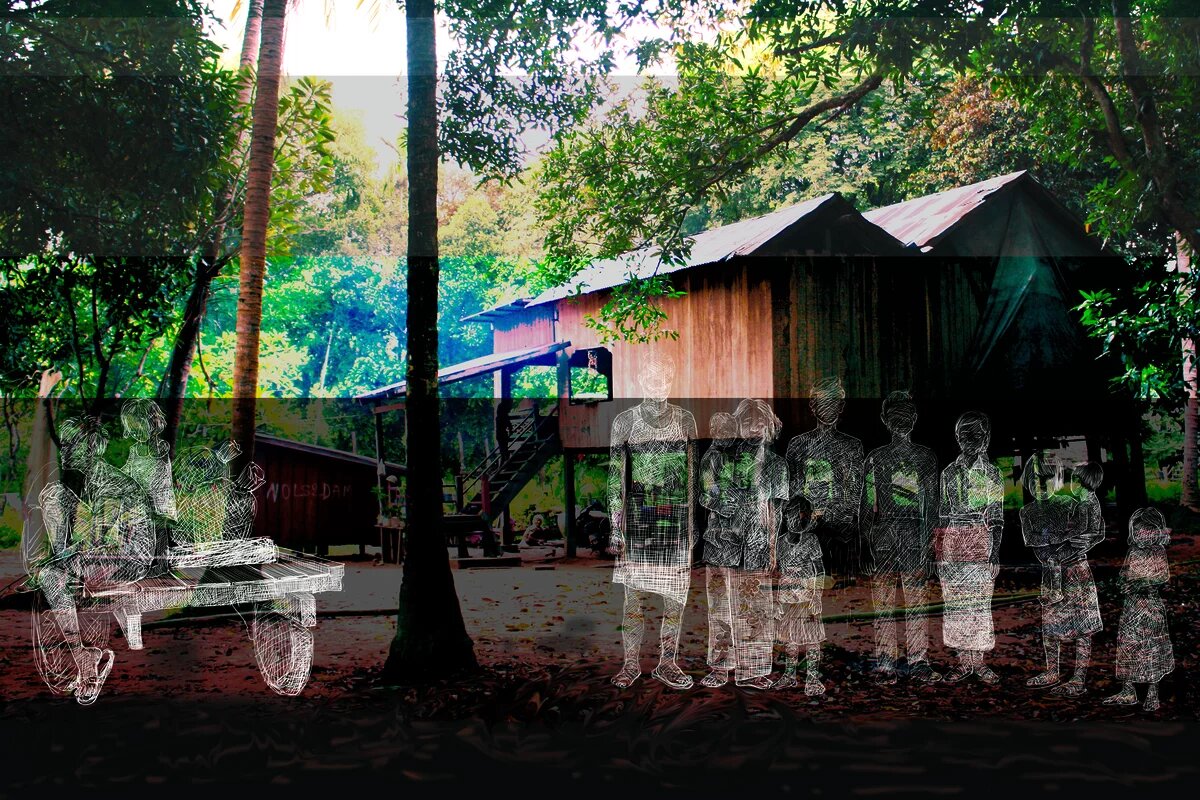

Phnom Penh has been a rich site to inform artistic productions for many artists. However, some artists such as Sao Sreymao go beyond the urban geography to consider what is happening to the Cambodian rural landscapes and communities. Born in Site 2 refugee camp[1] and grown up in northern Cambodia, Sreymao is an environmental educator and an artist. One project that best portrays her endeavour is Under the Water (2018), which consists of a series of photographs overlaid with digital sketches. Poetic and haunting, Sreymao constructs images of changing and disappearing communities along the Mekong River and its tributaries in the northern part of Cambodia affected by human-made environmental degradation, particularly floods caused by dam construction.

By the end of 2017, an entire village in Srekor commune, Strung Treng province, was completely submerged after the newly constructed downstream Lower Sesan 2 Dam closed its gates a few months earlier. As a result, about five thousand people, including many indigenous Bunongs, who lived by the banks of Sesan River for generations, were forced to relocate. Some of her images depict the now desolate houses in Srekor, covered with layers of grimy colour effects and drawings of presumably evicted families and villagers underwater. Some family figures stand in front of their homes as if marking their existence against the water washing. Behind them, the texts written on the houses indicate their protests against the Lower Sesan 2 Dam project. This violent incident is strongly felt in Sreymao's performance-sculpture work of the same project. She creates a miniature village with houses and human figures made of candles and places them on a lying sheet of mirror symbolising water. She then burns the candles and observes the melting and dissolution of the candle village.

Koeurm Kolab

Physical locality is not the only premise in which Cambodian artists situate in creating their artworks. Social and environmental realities at large are also grounds for examination by many. In a painting series titled Anonymous Heirloom (2020), Battambang artist and art teacher Koeurm Kolab presents today's confronting crisis caused by plastic use. She paints alluring and colourful sceneries of a world in which plastic waste from human consumption threatens the well-being and lives of humans, animals, and nature. Our world's plasticity cannot be better represented in one of Kolab's paintings titled "Collection," where reality and illusion conflate. From a distance, the painting seems to render a shoal of colourful, semi-translucent fish gracefully swimming in the peaceful, deep blue water. At a closer look, however, they are actually plastic bags. In another piece from the same series, “Float,” humans, as well as animals, birds, and marine lives, are tied to and suspended by a sheer amount of floating plastic bags filled with black gas blanketing the sky. Kolab's paintings are delightfully captivating yet illusive. They raise questions on whether we want to live and get lost in this colourful plastic world and to whom and how many generations we want to pass on this "heirloom."

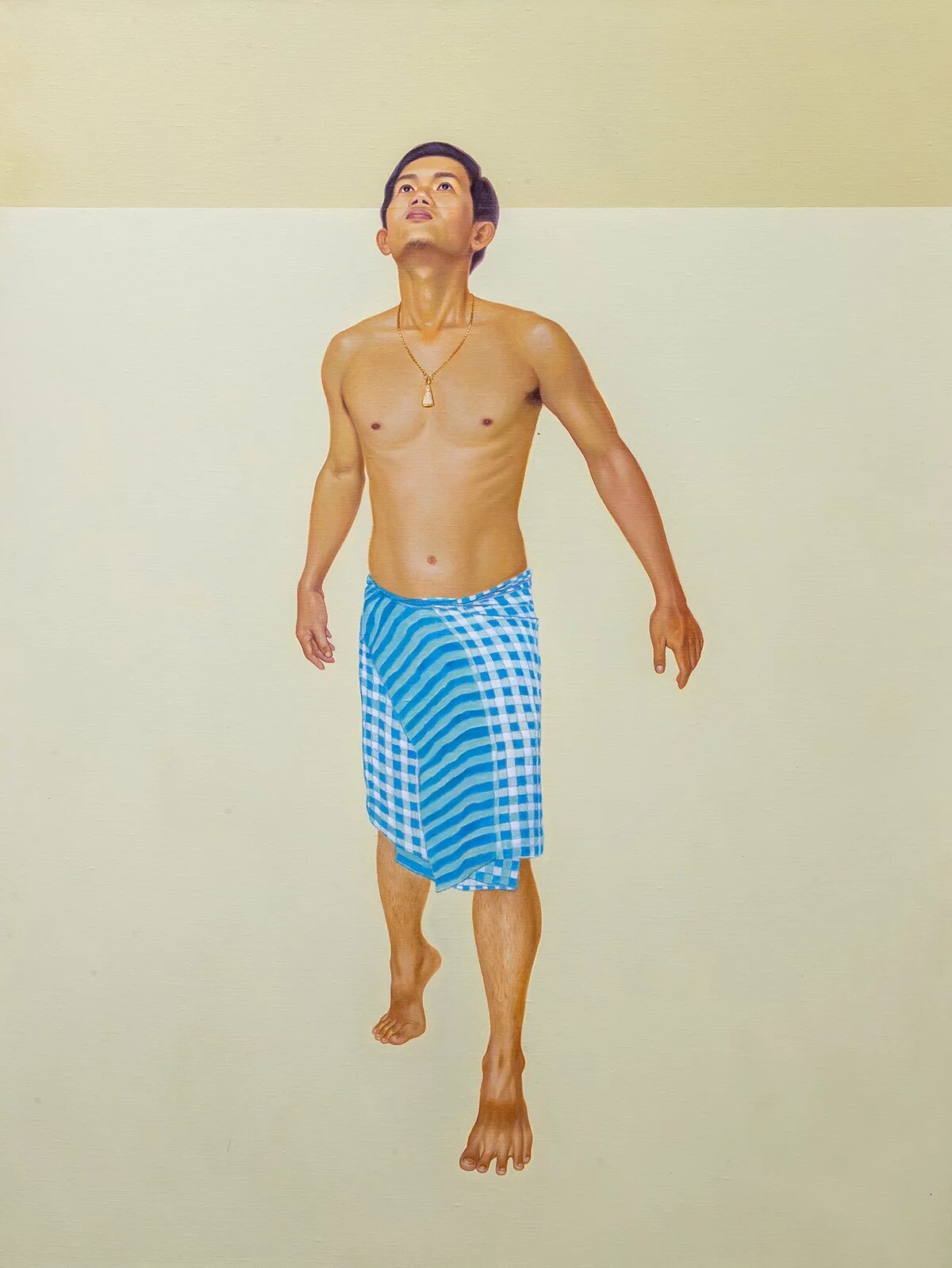

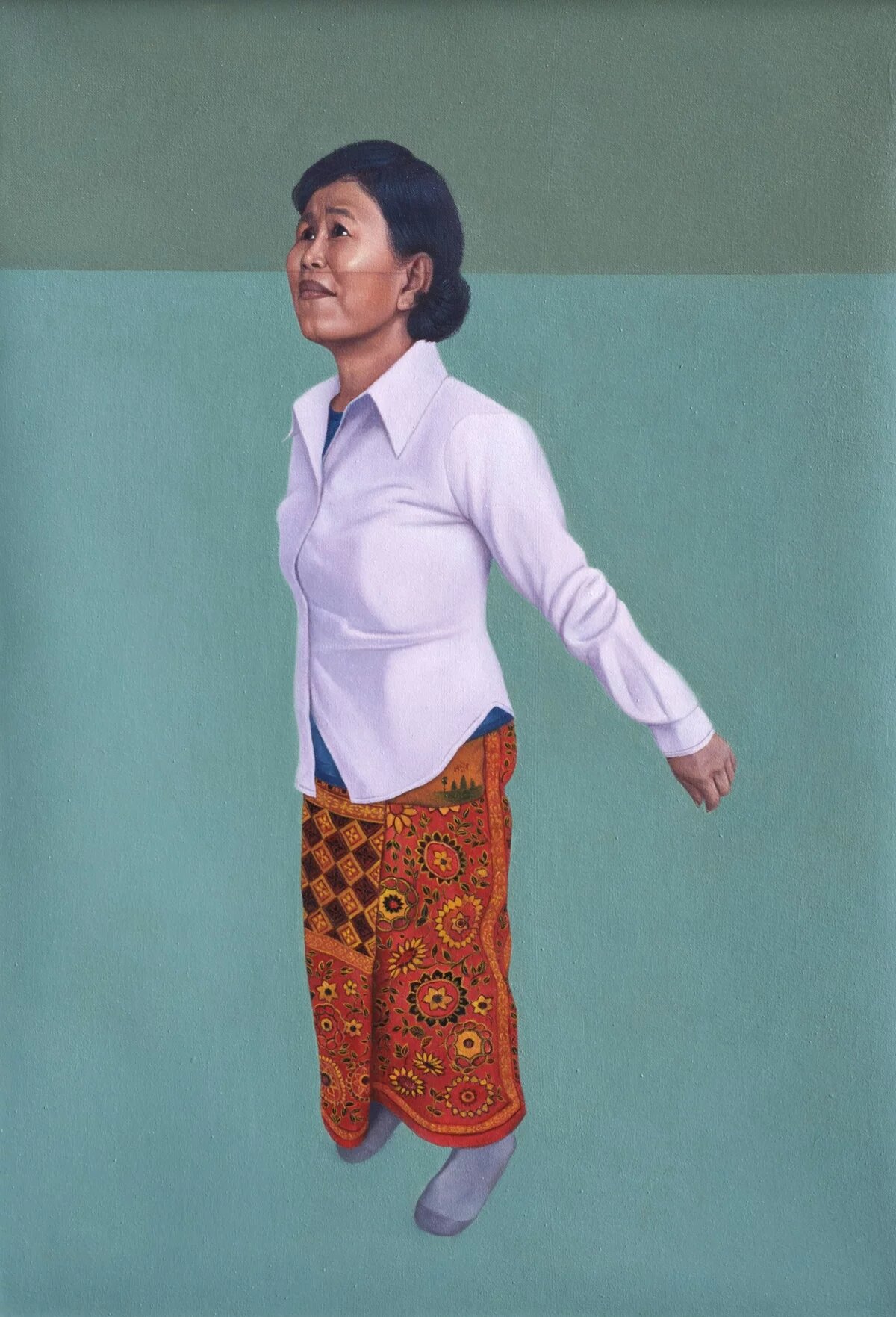

Chov Theanly

A sense of the struggle of human conditions in making it just above the water is dramatically illustrated in Chov Theanly's painting series The Rise (2019) and its preceding work. The self-taught artist introduces portraits of Cambodian people from various walks of life across ages, mainly those from low to average in their social and financial status. Among them, we see an Achar (elder man who assists in Buddhist ceremonies), an aunty, a female student, a young man wearing Krama (Cambodian scarf), a bride, and a Buddhist monk. Most of them stand on their toes and raise their heads. Behind them is a monochromatic background divided into two colour shades by a horizontal line cutting right just underneath the figures' noses. This minimalist representation speaks volumes to the humans' bare and most straightforward conditions. Nevertheless, these people do not appear to be drowning but instead propelling and rising up. Theanly's calm and chiefly executed paintings reflect a quiet tension between the graceful human agency amidst a pressing force.

Samnang, whose earlier work considers implications of urban development, goes on to observe the human, natural and spiritual world in another part of the country under threats of capitalist extraction. In Preah Kunlong (The Way of Spirit) (2016-2017), he produces a performance video and photographic work in collaboration with dancer Nget Rady. The project takes place in Areng Valley, in southern part of Cambodia, known as country’s contentious zone and one of Southeast Asia's last rich forest ecology. Preah Kunlong depicts a human body wearing various mask headdresses of endangered animals made of a local vine and performing in a lush natural landscape. The human body seems to morph with the heads of the animals transcending into another being. Here, human, animal, spirit, and nature are essentially merging and becoming into one. They breathe, squeak, chatter, roar, and weep, while dancing, combating, and moving between places as if claiming their territories. In Preah Kunlong, the artists transmit the concerns and the resilience of the indigenous communities in Areng, whose centuries of livelihood deeply connect with the forest and their protective spirits.

While political and social avenues for free speech are limited and prohibited, Cambodian visual artists find limitless forms of creative expression to critically examine many complex urban, social and environmental concerns. They move between conveying the direct and poetic messages in their artistic actions and visual language, enriching the audience's understanding of contemporary Cambodia. They also point to Cambodia's creative and resilient communities with rich indigenous knowledge and tactics that reflect, respond, and exercise their civic agency, even though their artistic engagement appears "quiet" to the large public.

[1] Site 2 refugee camp was the largest refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodian border and, for several years, the largest refugee camp in Southeast Asia. It was established in 1985 and closed in 1993.