In his essay, Jwan Tatar poetically outlines Kurdish identity in a Syria where fear is the link that binds all its residents.

“Today is just like yesterday,” they say. I laugh to myself to hear people criticize the axioms they swear by in the course of their daily lives, those they pass through as though they were softly crumbling walls, like those my grandfather built decades ago in the tumbledown old neighborhood. More often they walk beside these walls, careful not to touch them, afraid that, however soft, those walls might collapse onto them. As for myself, I take refuge in imagination, that powerful instrument that allows me, just one person among thousands inside Syria, to see.

The beginning

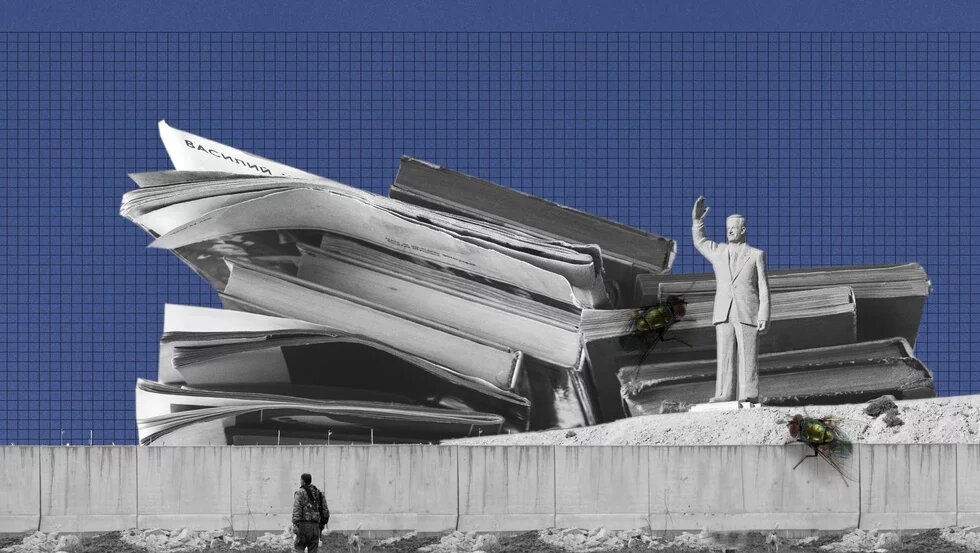

The entrance to the city of Amuda in northern Syria always takes me back to my childhood, which will remain forever suspended in the jaws of the statue that rises from its high concrete plinth as you approach. The statue is the height of ten tall men. It stands with its hands held high, a devilish smile on its face that reminds all who gaze upon it of their lost dignity. That smile also hangs suspended in my memory.

Later, as I grew older, I would see similar stone faces in all the cities I visited, whether in my imagination or in reality: statues of all shapes and sizes, full-length or busts, faces and faces and more faces, each one so like the others that you would think they were made by a single sculptor.

At the margin of the first beginning

I was on my way home after a shopping trip to the marketplace, oppressed by its looming statues. Intellectually, I understood everything that was happening around me even though the body I inhabited was small and frail. I was young, but already a long-suffering reader of the only three newspapers to reach the city, usually aboard a passenger aircraft from Damascus, half a day after they were published. The titles of these papers were etched in the minds of us residents: Al Thawra, Al Baath, Tishreen—Revolution, The Baath Party, October.

On my home, I stopped at the only bookshop in town to enquire if the latest editions had come in from the capital. Instead of answering, the owner flicked his gaze towards the television hanging on the wall behind me. As I’d entered the shop, I hadn’t noticed the voice of the Quran reciter on the broadcast, and I couldn’t understand the significance of this flicked gaze. I turned and looked, then shook my head in bafflement. The owner came over. “Hafez al-Assad is dead!” he whispered. The blood froze in my veins; my whole body went rigid. After a few moments more of his whispered explanation, I felt that fear would swallow me whole. He noticed my shock. He was sorting books on human development, tabloid magazines from Lebanon about celebrity scandals, and I told myself that he was attempting to deal with his fear, to brush away the fat green prison flies that were suddenly buzzing around him, sounding in his ears. Fearful, full of regret at having hissed that heavy, terrifying phrase—“Hafez al-Assad is dead!”—he shooed me out of his shop.

At the margin of the second beginning

My mother was raised in the countryside and lived her whole life in the company of injustice and fear. She would tell us that when my grandfather left Turkey, he had abandoned his plot of land and fled, along with many other Kurds, from the brutality of the Ottomans to settle in Syria, and that Syria had become the place he called home. She would talk to us about the bountiful village orchards on the Syrian side of the border, about the heavy rains that fell like a gift and a blessing on that remote area. My mother never knew but one leader, one president; she never realized that the police could be anything other than demons who sprang from the ground in the dark of night, figures who could help her cow little boys when the devil was in them: “Sit still and behave or the police will come!” “Calm down or I’ll throw you to the cops!” It was how she understood things: the police are demons.

That afternoon, the day that would become the first pushback against fear, my mother was quietly cleaning the courtyard of our large house when I rushed in, announcing in a loud voice, “Mother! Hafez al-Assad’s dead!” She trembled and rushed towards me, outstretched hand ahead of her, clamping it over my mouth as though trying to suffocate me: “Lower your voice, child!”

The multiple journeys of the beginning

They’re lucky, those who were not raised with fear: fear of statues, fear of the supreme leader’s endless portraits. They are lucky, those who have never seen state security headquarters and their multiple branches spread out through the arteries and veins of a city. And how wretched are those who have seen: the scar is there in their soul and will never fade. These security stations, each one papered by informers’ reports, their authors experts in concocting accusations and goading their agents to shoot: reports on a person’s Kurdishness, about the charge of reading in Kurdish (the only dignity left to us), accusing him of singing in a language that has been deliberately purged from its people’s lives.

Reports and accusations.

Those from my generation had already read accounts of the torture orgies in the supreme leader’s prisons, and so we were afraid: either staying silent or running straight into the arms of imagination in order to feel safe. But the humiliations never seemed to end, not even when the leader’s young son appeared. The fear was still there, rooted in our souls. The young man’s name was the alpha and omega: he was the leader’s son and what had been the leader’s was now his.

The story

It’s said that fear cannot be eradicated, that it just sleeps or dozes; that when it wakes it does so lazily, giving delusion the chance to intervene. The delusion that the fear has left you. Except that it is still there inside, inhabiting the most beautiful part of a person’s being, which is their mind. It sprawls like a king on his couch, sometimes lolling, sometimes slumbering, but able to wake any time it chooses. Fear does this for years. It has many stories, each different in form, but all with the same starting point. Fear forces you to come to terms with it, to surrender, so that when it does leave you, it feels as though you are missing something. You need fear every day of your life; surrendered, unresisting, you come to rely on it. It jumps out at you from the khaki uniforms of the police at checkpoints and leans its head out when you apply for a job at a government agency or university and have to bring a piece of paper stamped with “No criminal record”—a document that says you are innocent of the terror of the cells and the torture; innocent, and loyal to the Baath and the supreme leader and the state security branches and the statues of the leader that stretch from one side of the land to the other.

This is the story:

That you live without a shred of dignity; without knowing what dignity is, because dignity is a synonym for prison or torture or murder or any one of the quotidian humiliations of your life. The story is that to live means being without dignity, even if a policeman slaps you or abuses you, your ID card in his hand, while he demands you explain what your Kurdish name means in Arabic, then mocks the lot—you and the name and what it means—in an attempt to bring you down in the eyes of your terrified fellow passengers. And he might turn and slap the passenger next to you, the one who is laughing along with his mockery, so that hatred can start a new story between the passengers themselves. It is to fear your Kurdish name on the highway to Damascus, to hate the thought of the security officer taking your ID, of him making a joke of it, of him reveling in your humiliation.

The stories of dignity branch out and tangle, but those of fear describe a future based on the past. The future may look different, but it is a prisoner: a prisoner of the fear and terror of the past.

Time loops back on itself. They say that history repeats itself and they’re right, but though fear remains fear, it takes on different forms: a war here, an occupation there, and now here I am, in the present moment, fighting to suppress fear renewed once again.

Dignity’s door left ajar

For those like me, the daily scenes we witness are experienced like a film reel, our past reality projected over the present. The difference between the two is clear. Yesterday—almost literally yesterday—I was, like many of my peers, in flight from my mother tongue. Then we decided that it made no difference. Running away, I mean. It made no difference whether we ran or not, because time was always changing and would return everything to its place: paper back to logs, logs back to trees, and so on.

Now, through the eyes of my imagination, I see a far-flung landscape, stretching all the way to the void in the north: to Turkey’s fragile border fence. In the years before the war, young men would play football there, kicking up dust that settled on their bodies as they sprinted after the leather ball, while Turkish soldiers stared astonished at their litheness. Later, it would become a staging post for smugglers, for smuggling people out into God’s wide world and away from indignity, away from the daily humiliation that went everywhere with them. But the Turkish soldiers, as they’ve done since time immemorial, soon brought them face to face with their indignity again.

Dignity now

The screaming, swearing regime checkpoints vanished, but were soon replaced by others. These were manned by Kurdish forces, and these worked against the past: there was no swearing here; it was as though the checkpoints were saying, “We are here to protect you. To ensure your dignity is not offended.”

In his khaki uniform, clutching the Kalashnikov that is the only weapon he owns, eyes full of the memories of his martyred son, the sixty-year-old man trots over to ask you for your ID. He reads out the Kurdish name, then smiles and hands back the card. It is the same ID that the Syrian security agent mocked. Just a piece of card, with the names of your mother and father, the old family name.

The family: betrayed by fate and brought to live on a patch of earth about which the kindest thing that can be said is “surreal.” The same national identity card that bears your picture, that carries your dignity and your name, might be the cause of your humiliation by a Syrian security officer or bring a smile to a Kurdish soldier’s face as he brandishes it in the air and declares his desertion. And in the same way, when people took to the streets for dignity, many were deserters from the Syrian army and would brandish their ID cards to prove it. Inside government-controlled territory, the ID is used to show one’s name and ethnicity. But outside this territory, outside Syria, it is used to elicit pity. As if to say: who I am is the reason for the state I am in.

“Look at my ID. My ethnicity. Look what has happened to me… and help me.”

Memory

In my dreams, I hear the Syrians chanting for their dignity. Awake, I’ve often seen the crowds demanding it. I try searching my memories for this dignity, and when I see how things are now, what has happened to us, I admit failure: diaspora after diaspora, while those who remain behind spend their days chasing after a crust of bread.

I wonder, are these chants themselves a prisoner of the past? This is the question we face today. And there’s no answer… none.

Where I live in Syria, I almost never hear the word, though just a few years ago it was in every TV news report, in headline font across every front page: “Syria of Dignity!” “The Dignity of Syria!” There’s nothing like that now. Now, Syrians are trying to make it through the day. For them, dignity means not being hungry or cold; it means their children not having to comb through the garbage in search of something to eat, or their landlord not throwing them out to live in the street. Dignity means not ploughing through heavy seas only to end up in the belly of a whale.

There were so many whales. Whales that swallowed dignity. Whales that swallowed Syrians. Politicians and soldiers. The men of state security and state security branches still treat people like whales, their bodies and minds never tiring of the constant back-and-forth of interrogation. This is what Syrians have reaped, not because they are weak, but because the agencies of the state are genetically programmed to humiliate: behaviors passed down endlessly from generation to generation.

The Syrian is a number

They numbered the dead from one to a hundred. They couldn’t decide who should go first into the grave. Some impersonated the dead in order to become a number; some volunteered to carry the coffins after each new death; some, after long years of carefully picking their way along, decided not to wait at the checkpoint, and ran.

The dead spent their lives holding their ID cards up to the faces of soldiers and the world. Numbers… numbers… They don’t carry knives or bullets or guns, but documents for embassies and reservations at mean little hotels. “They took our children from us,” they say, “and threw them to the hungry sea.”

Maybe I wasn’t paying attention, or perhaps I was pretending to be grief stricken in order to get myself a number of my own. Or maybe I was given a number, and they took the pen the way they do with everyone else and wrote four digits in the four boxes on my forehead.

The whole world has seen them naked, and I have, too. There’s no one who hasn’t seen them in the photographs, stretched out murdered in prison or with their blood running in the streets. But we stanched the wound in our hearts then bolted the gates, and they died.

In my imagination I make them cleaners in threadbare red caps, chewing over the idleness of the night before and rubbing the darkness from their eyes. They eat breakfast beneath an imaginary tree in the courtyard of an imaginary building, kissing their children who are late to join them. They look up at the buildings looming over their souls: high as heaven itself, the buildings pressing down. Their clothes are filthy and they show their ID cards to the governor, saying, “What can we do with this piece of card? The information here isn’t ours our ghosts are free now. Now we flow in life’s veins.” One day, they believe, the narrative will do them justice; that it will arrange neat rooms for them in imagination, and fulfil the promise made. By the gates they notice ripped books, broken pens, photographs of the graves and plastic containers. “Souls imprisoned in bags tied tight so the smells can’t escape.” So they speculate beneath a searing morning sun. One of them sings mournfully from a dampened song sheet: “My children are abroad. My children are within the books.”

The current reading

When we were young (and we still are young) we read Riyad al-Saleh al-Hussein, who once wrote: “O Syria, wretched as a bone between a dog’s teeth.” We never saw the Syria where we lived or which we imagined, but we saw the dog. We saw and met many dogs, sprawled motionless on the pavements, idly watching passersby, while others worried and gnawed at hope, bit women and children and old people, their howls describing a future of war and hatred.

My ID card is on the table in front of me. I am looking at it and thinking about saying to my infant son, “Take it. Throw it to the dogs, down a well, so that you, the next generation, can see how our dignity and daily lives were lost to us. These numbers beneath the eagle of state the eagle from which we became, perhaps always were, estranged betrayed us. Take it, my son, and tell your children what it’s good for now: not good enough to buy you a scrap of bread or a single dose of medicine.”

Author: Jwan Tatar (*1984 in Amude, Syria) is a Kurdish-Syrian poet and translator. He lives in Syria. He has already received numerous writing grants and prizes, including the 2022 Mediterranean Poetry Prize and the 2010 Prize of the Second Forum for Proselyrics in Cairo. Through the Goethe-Institut and Ettijahat Independent Culture he received a writing grant for his prose volume ila al-`alam dur (English: eyes to the flag!)

Translation from Arabic: Alice Guthrie is a freelance translator, writer, editor, and researcher. Her translations have appeared in a broad range of international venues and publications since 2008, recognized with various grants and honors—most recently the Jules Chametzky Translation Prize 2019. Among her ongoing projects is the translation of Moroccan feminist Malika Moustadraf’s complete works. As a commissioning editor she is currently compiling the first ever anthology of queer Arabic writing, set to appear in parallel Arabic and English editions in 2021.

Curation: Sandra Hetzl (* 1980 in Munich) translates literary texts from Arabic, among others by Rasha Abbas, Mohammad Al Attar, Kadhem Khanjar, Bushra al-Maktari, Aref Hamza, Aboud Saeed, Assaf Alassaf and Raif Badawi, and sometimes she writes too. She holds a Masters in Visual Culture Studies from the University of the Arts in Berlin, is the founder of the literary collective 10/11 for contemporary Arabic literature and the mini literature festival Downtown Spandau Medina.

This essay is part of our series "Reminiscence of the future". To commemorate ten years of revolution in North Africa and West Asia, the authors share their hopes, dreams, questions and doubts. The essays indicate how important such personal engagement is in developing political alternatives and what has been achieved despite the violent setbacks.

In addition to the series we also address the ongoing struggle against authoritarian regimes, for human dignity and political reforms in various multimedia projects: For example, our digital scroll story "Giving up has no future" presents three activists from Egypt, Tunisia and Syria who show that the revolutions are going on