In mid-September, the European Union (EU) Parliamentary resolution called on the international community to stop the construction of the controversial the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) in East Africa. This has been preceded by years of civil society resistance. Too much is at stake for nature and people.

The European Parliament called on the international community to exert maximum pressure on the governments of Uganda and Tanzania to stop the construction of the controversial oil pipeline in a resolution adopted on 15 September 2022. In addition, Parliament is calling on the French company Total Energies to put plans for this mega-project on hold for a year and to look for more environmentally friendly alternatives.[1]

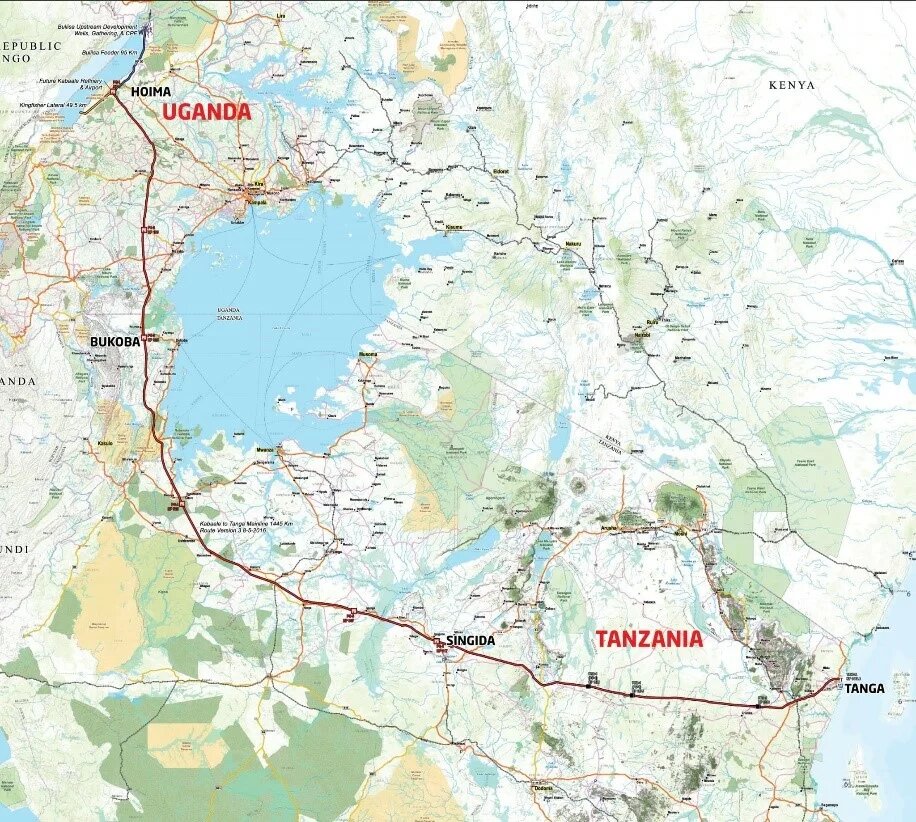

According to Stop EACOP an alliance of organisations and individuals who are against this mega project, this project stretching for nearly 1,445 kilometers would have disastrous consequences for local communities, for wildlife and for the entire planet.

The project threatens to displace over 18,000 households and farmers from their land. Besides, it poses significant risks to water resources and wetlands in Uganda and Tanzania – including the Lake Victoria basin, which over 40 million people rely on it for water, food production and is a key economic component in this region.

The pipeline would rip through numerous sensitive biodiversity hotspots, and risk significantly degrading several nature reserves crucial to the preservation of threatened elephant, lion and chimpanzee species.

There has been human right abuses to the critics of the project. As recently as 2021, Uganda forced 54 independent NGOs working on freedom of expression and human rights to close down and cease their activities.

What does EACOP stand for?

East African Crude Oil Pipeline, or EACOP - These five letters describe a gigantic energy project that will most likely keep East Africa in suspense for decades to come. When oil was discovered sixteen years ago under Lake Albert in Western Uganda, it quickly aroused desires in one of the poorest regions of the world[2] for the rapid development of this fossil wealth. However, this was not without problems and conflicts.

Plans call for the oil pipeline to run over or under the land of an estimated 60,000-117,000 people, who have so far received only little or inadequate compensation.[3]

So far, approxomately 7,000 people have already been resettled in preparation for the construction of this colossal oil pipeline. In the event of an oil leak, the livelihoods of four million people who rely on Lake Victoria as a fishing ground would be threatened.[4] The risk of such water pollution from an oil leak is also present because the oil pipeline runs along tectonic cracks in an earthquake zone.[5]

An oil project in a national park

The site of the oil discovery is located at Lake Albert directly on the border of Uganda to the D.R. Congo in the Murchison Falls National Park. This would make EACOP not only the first oil project in a nature reserve in East Africa,[6] but also one of the most biodiverse regions in Africa, home to more endangered and endemic species than anywhere else on the continent.[7] As a landlocked country, Uganda has no direct access to the sea, which is why the crude oil has to be transported 1,444 kilometres to Tanga at the Tanzanian coast in order to be sold on the world market. Since the crude oil contains little sulphur, it is very viscous and must therefore be heated constantly to 50 degrees Celsius in order to be transported.

"Energy integration" instead of energy transition

Due to this complexity of the project, experts consider EACOP to be one of the last large oil projects of its kind before the global energy transition gains full momentum.[8] However, the Ugandan government does not want to speak of an energy transition, but rather of an "energy integration" with oil and gas as well as an additionally planned nuclear power plant in the Buyende district in eastern Uganda.[9]

Proponents of the oil project promise up to 100,000 new jobs and a projected growth of the Ugandan economy.[10] Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni pointed out in a much-quoted piece in the British Telegraph that all countries of the world would remain dependent on oil and gas for the "foreseeable future" and that it was an injustice that countries like the US or the UK would increase their production of fossil fuels in the face of the war in Ukraine, but a country like Uganda would be barred from doing so.[11] In these times, it would be easier for Western leaders to impose ambitious climate protection targets in the Global South than at home.[12] Others state that energy poverty on the African continent would lead to increased deforestation and environmental degradation, which is why oil extraction as a transition to a sustainable economy would actually end up benefiting the environment.[13]

It is true that Africa’s energy demand is projected to be 30 per cent higher in 2040 than it is today, compared to a global increase of only 10 per cent.[14] Moreover, Africa's share of the world's population is about 15 per cent, but its share of global Co2 emissions is only four per cent.[15] Nonetheless, it cannot be ignored that EACOP would multiply Uganda's annual emissions by a factor of seven, meaning that the East African country would produce about as much CO2 as Denmark.[16]

Is this not corporate colonialism?

But EACOP is not entirely an East African project. Uganda and Tanzania each hold only 15 percent of the shares in the planned oil project. 62 percent of EACOP are in the hands of the French oil company Total Energies and eight percent are in ownership of the Chinese state-owned company China National Offshore Oil (CNOOC).[17] In addition, Total will be granted a tax exemption for ten years from the first day of oil extraction.[18] Indeed, most of the contracts for this multi-billion dollar project went to foreign companies, as a result, local companies in Uganda and Tanzania will only have a supporting role in the construction and operation of the oil pipeline.[19]

Consequently, estimates now suggest that instead of the tens of thousands of new jobs announced; only 3,500 will probably remain at the end of the construction work.[20]

The oil is destined for sale on the world market. However, proponents promise the construction of a refinery costing four billion US dollars, which will be marketed in East African. However, according to news reports, the Ugandan government is having great difficulty securing the funding for a local refinery - and now had to admit that such a refinery project could not be realised before 2027.[21] Critics of EACOP therefore fear that this oil oil production in Uganda could have similar consequences as in Nigeria.[22]

The West African country has unfortunately become an example of the so-called cursed resource: When oil wealth rather than prosperity causes rampant corruption and, as a result, even more poverty.[23] Due to decades of massive pollution from oil production, the average life expectancy in the Niger Delta is now only 41 years.[24] Corruption, poverty, environmental degradation has become the norm. As a result the despite touted as a blessing, oil has become a curse to Africa's largest and the world's sixth-largest export nation of crude oil. Since 1980, most countries on the African continent have become more prosperous and peaceful; but only those without oil resources.[25]

Legitimised destruction of biodiversity

In response to this criticism, the French company Total wants to ensure that "nature will be in a better situation than before the oil project".[26] Total intends to achieve a so-called "net biodiversity gain".[27] Total promises to minimise the impact of construction work and drilling on the Murchison Falls National Park and to protect nature elsewhere, so that the bottom line is a "net zero gain". For example, Total wants to reduce "human pressure" on the national park, employ 50 per cent more park rangers and also support a project to reintroduce the endangered black rhino in cooperation with the Uganda Wildlife Authority.[28] In addition, pumping equipment for the oil pipeline shall be powered by solar energy and further destruction of biodiversity shall be prevented by discouraging local people from local land use.

The idea behind this construct of "biodiversity offsetting", which has become increasingly popular in recent decades, is that every piece of nature destroyed by an industrial enterprise must be protected or even restored elsewhere.[29] However, "biodiversity offset" promises have an infamous history in Uganda. For example, as compensation for the controversial construction of the Bujagali Hydropower Dam, promises were made to protect "comparably important" waterfalls and riverbanks elsewhere, only to build another dam at that site a few years later.[30]

Moreover, scientific studies have found that the effectiveness of so-called "no net loss biodiversity policies" has not been proven and could not lead to any noticeable success, especially in forested ecosystems.[31] Instead, the promised compensation for the loss of biodiversity would allow for the destruction of the same, especially in designated nature reserves.[32]

Since being renamed Total Energies, Total has presented itself as a modern company that wants to achieve ambitious climate protection goals. For example, the oil company wants to achieve "net zero emissions" by 2050.[33] However, many view these statements with great scepticism. For instance, according to a new study by three renowned universities, Total is aware of the consequences of climate change since 1971, and as a result began to deliberately fuel doubts among the public about the scientific consensus on the causes of global warming from the 1980s onwards.[34]

Forces of civil society

Therefore, the StopEACOP campaign has received a lot of attention in recent months.[35] Through public pressure, local activists in Uganda and Tanzania, but also young people from Fridays For Future or other international organisations, have succeeded in getting twenty major international banks to publicly declare their opposition to supporting EACOP.[36] For example, Deutsche Bank, which has financed Total Energies with billions of dollars in the past, has announced that it will not participate in EACOP after protests by activists from Uganda and Germany.[37] If one also considers that, not least due to the war in Ukraine, the cost of the oil pipeline has recently risen by 30 per cent to over five billion dollars,[38] it becomes clear that the StopEACOP campaign certainly has a chance of success in times of the Paris Climate Agreement.[39]

However, supporters of the EACOP project have pinpointed the interference of American and European environmental protection organisations on this cause.[40] But as the pipeline's sponsors are scattered all over the world, EACOP is particularly well suited for an international campaign, not only factually but also practically.[41] For instance, young climate activists are protesting against Total Energies in France[42] or speaking to Pope Francis in the Vatican[43].

At the UN Climate Summit 2021 (COP26), countries such as Germany, France, the UK or the USA promised to stop direct public support for international fossil energy projects by the end of 2022.[44] Therefore, in a world where the largest economies have pledged to reduce their emissions in the face of the climate crisis, the East African Crude Oil Pipeline has become a litmus test for the exploration of large oil resources in the age of Net Zero.[45]

The EU Parliament is now calling for a one-year pause in construction to seek a more environmentally friendly route for the oil pipeline.[46] But even then, critics and protesters would not go quiet. Even if the pipeline was to take a different route, the main problem of this multi-billion dollar project would not be solved. As Kenyan environmental activist Omar Elmawi keeps pointing out, "EACOP looks more and more like corporate colonialism.".[47]

About the author: Adrian Amann is a Heinrich-Böll-Foundation scholarship recipient and is studying law in Berlin. During his semester abroad in Nairobi, he worked intensively on the East African Crude Oil Pipeline.

[2] Uganda: 41 percent of the population live on less than 1.90 US dollars a day: https://data.worldbank.org/country/uganda

[18] Please see page 53 of the EACOP Special Provisions Act 2021.