Does the future of French agriculture lie in agroecology? Long shaped by a productivist model that has eroded jobs and destroyed biodiversity and the climate, farming now faces a dual challenge: preserving the environment while creating rewarding, sustainable employment. Between broken promises of modernization and the rise of greener practices, this article explores how the agroecological transition could also become an economic and social lifeline for rural territories.

Conventional farming has enjoyed the support of French governments for decades, often at the expense of small farmers’ livelihoods and of consumers’ health. It builds on a promise: making food accessible for everybody (“feeding the world”) while ending rural poverty and modernizing farm jobs by making them less physical. For the most part, France and Europe have failed to deliver on this promise. This is why, in order to pave the way for more viable alternatives, a number of farmers are now engaging in agroecological practices. The environmental benefits of agroecology are unquestionable, but what about its socioeconomic benefits? Can it really create and maintain sustainable and rewarding jobs, both on and around the farm?

Infinite Growth and Easy Jobs: The False Promise of Conventional Agriculture

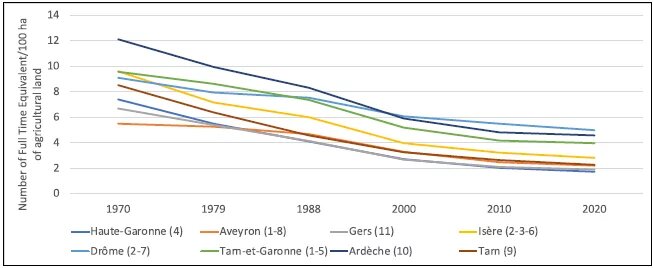

In the aftermath of the Second World War, European governments implemented a new agricultural model whose goal was to secure access to food for all Europeans. Farm work was also to become less physically exhausting thanks to modern machinery mostly coming from the other side of the Atlantic. In line with the new economic model of rapid productivity and growth, agriculture, too, was expected to constantly improve its productivity, e.g. by mechanizing farm work. The search for more yield and short-term profitability led farmers to specialize in one or a few production types. In the French Limousine Mountains for instance, cattle breeding developed quickly in the 1980s because it was less work-intensive than sheep breeding. Specializing in cattle breeding helped simplify farming methods and make cattle farms larger, leaving many peatlands unused. Moreover, since cattle breeding was less work-intensive and more productive and farms were getting bigger and bigger, on-farm job numbers declined: today in France, only eight percent of the number of farmers of 1950 remain. This phenomenon is now acknowledged as one of the main reasons for rural decline, both in terms of social life and of employment opportunities: people living in rural areas tend to move to cities in search for better living conditions.

According to official data, one in three farms and 80 000 farm jobs disappeared between 2000 and 2020 while the mean size of farms doubled within 30 years. In France, large farms (136 ha or more) are the only farm type whose number increased in the last decades. More worryingly, France is also seeing big companies – with business activities not necessarily related to farming – buy extensive farm plots, some of which thousands of hectares large. Their purchasing power is much larger than that of small farmers, which pushes up land prices dramatically. And so the vicious circle starts: the larger the farm, the more expensive and less accessible it becomes to a small-scale farmer wishing to set up in business.

Last, but not least, as conventional agriculture strongly relies on synthetic pesticides, fertilizers, and hedge cuts in order to expand farm slots, it seriously jeopardizes biodiversity and climate. In turn, extreme events such as droughts and floods, which are only getting worse due to climate change, have extremely negative impacts on yield and thus on (current and future) jobs. As agricultural production today already tends to stagnate, prospects in the mid- to long term are bleak.

Agroecology: A Promising Alternative to Conventional Farming

Despite European governments’ recent tendency to cut off support to the Green transition, the demand for more environmentally friendly food products remains strong, creating promising market for agroecological products. However, this cannot occur without real support from policymakers. Contrary to popular belief, the benefits are not only environmental – the positive economic impacts can be numerous, too.

First, the strong reliance of conventional agriculture on agrochemicals as well as on high-tech material has a cost. Small-scale farmers find themselves – willingly or not – caught in a spiral that is increasingly hard to escape: as others invest in better machinery and chemical inputs (whose prices are tied to the volatility of international markets), they are forced to follow suit in order to remain competitive, which often means sinking deeper into debt. By contrast, agroecology requires no agrochemicals and no high-tech machinery: shifting towards it would hence reduce farmers’ dependency on agribusiness and potentially improve their livelihoods.

While over 80 recent studies demonstrate that ecological transitions offer more agricultural jobs per unit and require more workload than conventional farming, empirical evidence also highlights agroecology’s benefits on sustaining rural jobs.

In general, the French mountains are less suitable to conventional agriculture because they offer less space for big farms, and the harsh climate conditions demand more workload per hectare. Hence, in many mountainous landscapes, small-scale agriculture has remained the norm, maintaining more farm jobs than elsewhere, but also favoring the rise of sustainable tourism, which in turn has created and diversified local jobs.

Not to mention that these jobs are the opposite of what anthropologist David Graeber framed as “bullshit jobs”: although working on ecological farms is often more time-intensive, it is also more rewarding. Indeed, knowing they are valued by, and directly connected to, local consumers can greatly improve farmers’ mental well-being. At the same time, closer ties with farmers help restore respect for their profession – people know where their food comes from and feel reassured about its positive impact on their health and the environment.

In this sense, agroecology offers a more humane, inter-relational alternative in which farmers, but also rural residents and consumers regain their power from agribusiness companies like Bayer and Yara. By improving the connection between producers and consumers through shorter food chains, agroecology creates a multiplicity of fair and local markets, involving direct, but also indirect “farmer-to-eater” exchanges through the development of regional businesses that sell agroecological food and derivatives. In this way, it offers hope and a viable future to rural areas often neglected by public authorities, while tangibly strengthening local communities.

The EU Agrifood Sector Is in Desperate Need of a Radical Shift

Why, then, aren’t we all massively shifting towards agroecology? As in so many other cases, the answer lies in a bunch of four words: lack of political will. The agrifood system is quite complex, hence a radical paradigm shift is needed in order to achieve a really green and fair transition.

Here are a few important measures that France and Europe should implement in order to bring about the much-needed change.

Reform the CAP

The EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) subsidizes farms according to their size: the larger the farm, the more subsidies it receives. Although agroecological farms tend to have higher employment rates and higher crop yield per hectare, they are also usually smaller; hence, they get less subsidies than big conventional farms. For years now, many NGOs, farmers and experts have been demanding a broad CAP reform so that farms that create more jobs per hectare get more support from the EU. Redirecting and increasing subsidies towards agroecological farms would also help offset the increase in labor costs, as the work would be better compensated. At present, the prices of goods produced through agroecological practices are higher than conventional ones, but not high enough to offset the additional labor required on these farms.

Increase Financial Support for Sustainable Farming Practices and Healthy Food

The main challenge is therefore the following: how can we guarantee that jobs in the agroecological sector are truly well paid and rewarding, while making sure that food prices remain accessible for everyone? It is crucial to bear in mind that farmers have the right to a decent income, farmworkers have the right to decent wages, and consumers have the right to adequate food. Agroecology offers the potential to combine all three, but only if policymakers and retailers agree to do their part.

First and foremost, it is France’s and the EU’s duty to guarantee these fundamental rights and they can do so by better subsidizing people’s access to agroecological food, thereby simultaneously securing market opportunities for local farmers. Many local initiatives, often led collectively by civil society and green or left-wing politicians, show the way forward. In Montpellier, the Food Social Security (Sécurité sociale de l’alimentation), and in many Green cities, the provision of local, organic and vegetarian menus in school canteens, all have a very positive impact in that regard.

Secondly, if we want to make agriculture work more attractive, farmers’ incomes and farmworkers’ wages should definitely be decent, i.e. much higher than today. In order to ensure that this change does not negatively affect the middle and lower classes’ purchasing power, the additional cost should primarily be borne by processors and retailers, whose profits have reached record highs in recent years. Farmers should be able to sign fair contracts with the agro-industry, based on actual on-farm expenses. What is more, our policy-makers should help them achieve this.

More Support to Research

In its current state, research shows rather positive outcomes, both quantitatively and qualitatively, for employment on agroecological farms. However, empirical evidence for whether and how agroecology improves labor conditions is scarce, and for now, the findings are ambivalent. Among other things, academic research is lacking about health, including mental health impacts of working on agroecological farms. Moreover, though farmers and farmworkers generally experience working on agroecological farms as more meaningful than on conventional farms, labor there is often underpaid and working conditions are not always good – these farms partly rely on international volunteers or migrant workers with poor legal protection. These situations are in no way viable if we want to attract farmers in the long term.

Sustainable Agriculture Is a Matter of Choice

While agroecology has a lot of potential to improve employment rates, working conditions and health, its actual benefits mostly depend on the support it gets or doesn’t get from those in a position of economic or political power. At the end of the day, it is a matter of choice: if we want agriculture and food to be good for our planet, for our farmers and for ourselves, rather than for a handful of agribusiness billionaires, we had better fight for it collectively.