For thousands of years, rice has been more than food. It has been culture, memory, and survival. In South Korea, a few determined farmers are bringing back native rice varieties lost to history. Their rainbow-colored fields tell a story of resilience, creativity, and a future rooted in the past.

The Grain That Shaped Civilization

For as long as people have tilled the earth, grains have shaped the course of human history. The documentary Rice and Wheat: 20,000 Years of Struggle makes this point clear. Among all grains, rice and wheat have been more than daily nourishment. They were energy for survival, the foundation of civilizations, and pillars of culture.

Today this foundation faces new pressures. Climate change and the degradation of ecosystems place the world’s staple crops in a fragile position. Just as past generations struggled to cultivate and preserve grains, future generations will face new challenges in cultivating the foods that sustain us.

In Korea, rice is the grain most closely tied to daily life. It is called bap and appears on the table at nearly every meal. Yet few pause to consider the story inside each grain.

What Makes Rice “Native”?

How many kinds of rice grow on this planet? Some researchers have identified about 5,000 varieties worldwide. Others suggest that if classified in more detail, the number could reach 100,000.

When people imagine wheat, barley, or rice, the picture is usually a golden field. But those who see a field of Korea’s native rice are often astonished. The grains appear in rainbow-like colors and shapes, each with its own distinct taste. In Korea, farmers are working to revive varieties that disappeared during the Japanese colonial era. They call native rice “an old future.”

The grains appear in rainbow-like colors and shapes, each with its own distinct taste.

Back in the 1910s, when Korea was under colonial rule, officials surveyed rice across the peninsula. In two years they collected nearly 4,000 samples and documented more than 1,400 native kinds in the Comprehensive List of Korean Rice Varieties.

But what does “native” really mean? A 2016 report from Korea’s Rural Development Administration gave a simple definition: plants that either grew naturally in Korea or had been cultivated here for generations. For rice, this meant varieties not imported or genetically engineered, but those that gradually adapted to local soils and climates.

Farmer LEE Geun-i of Woobo Farm, one of the leaders of the revival, explains it more personally: native rice is “rooted in the history of rice cultivation on the Korean peninsula, carrying its own locality, ecology, culture, and history.”

Seeds with Stories

Korea’s native rice often grows taller than hybrids, its husks bristling with fine hairs called kkarak, and it resists pests with surprising strength. Above all, it carries vitality and diversity that set it apart.

The names themselves are stories. Noin-dadagi, like an elder’s white hair. Hwado, glowing red like fire. Metdoechi-chal, as coarse as wild boar bristles. Black Sesame Rice, dotted like sesame seeds. Soemeori-jijang Rice, pink and shaped like a cow’s head. Willow Rice, slender as a tree. Barley Rice, bearing the likeness of barley. Joljjang Rice, short and compact. Gawi-chal, once eaten during the Chuseok festival.

One variety carries a legend of its own. Jodongji was so prized for taste that it was once promoted as a recommended cultivar under colonial rule. Its story begins with JO Joong-sik, a farmer in Yeoju. He noticed a single stalk that looked different, saved its seeds, and found they grew fast, yielded well, and tasted superb. The variety spread quickly across central Korea. Out of respect, neighbors added the honorary title dongji (同知; meaning “assistant magistrate”) to JO’s name, and it became the variety’s name. Today, both the city and local farmers are working to have Jodongji recognized as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

From Decline to Revival

Despite such richness, native rice nearly disappeared. Only small amounts survive, and many Koreans do not even know it exists. The decline began under colonial rule, when self-sufficient farming was dismantled and Japanese varieties, higher-yield and easier to mill, replaced native ones. After liberation, development-focused policies continued the trend, leaving little room for older seeds.

Yet the story has not ended. In recent decades, farmers began questioning this loss. Small groups started saving seeds, planting again, and teaching others. Their work shows that what was nearly forgotten can return. A grain is more than food; it holds history and culture. The revival of native rice is proof that both can be planted again.

Farming is also about culture and creativity.

Farmers as Guardians

Although native rice has nearly vanished, some farmers are determined to bring it back. At the center is the National Native Rice Farmers’ Association, led by figures like LEE Geun-i of Woobo Farm. For nearly fifteen years, he has worked as a guardian of native rice.

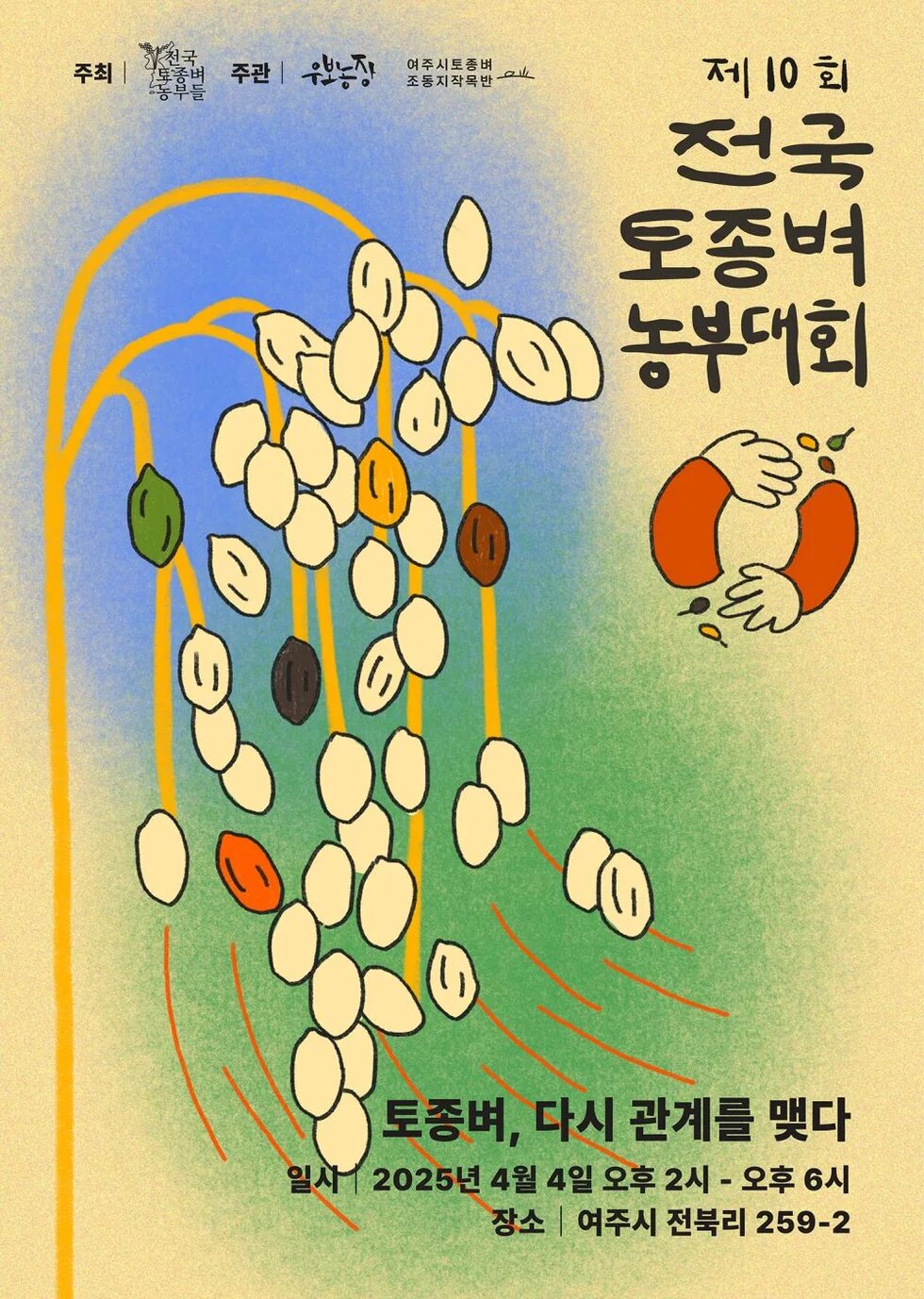

Each spring, before planting, the association holds the National Native Rice Festival. Farmers exchange seeds and present products made from native rice: makgeolli, beer, ice cream, chocolate, sweets, and syrup. Visitors enjoy music, crafts, and community. These gatherings remind people that farming is also about culture and creativity.

LEE recalls that in late Joseon times, nearly every village brewed its own liquor. Change the rice, and the yeast changed; change the water, and the taste changed. Around 1910, Korea had more than 375,000 taverns, each with its own flavor. That tradition faded with colonial rule and industrialization. LEE dreams of reviving it, not as nostalgia, but as a modern culture of diversity and pride.

In 2025, he launched two projects. The Self-Sufficiency Rice Plot lets city dwellers join in a full cycle of farming—sowing, transplanting, harvesting, milling—and learn the value of food they grew themselves. The 108 Taverns Project invites people to brew traditional liquor, aiming to restore identity and community. That same year, Woobo Farm also began the Rice Flower Tour, where families walk through fields in bloom and feel the quiet joy of rice swaying like dancers in the wind.

Rainbow Fields Across Korea

Beyond Woobo Farm, others are protecting native rice. In Changwon, beside Junam Reservoir—famous for migratory birds—stands Junami Farm, run by WOO Bong-hee and his wife, JUNG Sun-hye. They have long cultivated native rice on the fertile Gimhae Plain, where the Nakdong River meets the sea.

WOO is clear about his choices:

“First, they must not fall. Second, they must taste good. Third, the yield must be steady.”

He now farms about 33 hectares, with native rice making up 30 to 40 percent. He focuses on southern varieties like Hwado, Gwido, Red Chanarak, Jinan-do, and Metdoechi-chal.

For WOO, native rice is never fixed. “Hwado used to be deep red, but now its awns have turned white, likely adapting to local soil and climate.” Not all varieties thrive everywhere. “Bukheukjo from the north does not suit Changwon.”

One of his paddies was once a lotus pond. Now rice grows there, with lotus leaves rising among the stalks. He also farms near Gimhae Airport, aiming to use part of the harvest as feed for migratory birds in winter. Such ecological farming, he believes, needs support from both citizens and policymakers.

Further south in Jeollanam-do, farmer KIM Young-dae runs Maktong Rice Mill. The name Maktong means “clear poop,” a playful reminder that clean food leads to a clean body. KIM avoids heavy machinery, farms by hand, and distributes diverse native rice varieties. Some call him eccentric, but for KIM, conviction matters more than convention.

Beyond Farming: Culture, Community, and Art

The farmers who revive native rice have hands that are rough and strong. What they cultivate is not just old rice. It is memory restored, cultural diversity held in grain, and a way of reinterpreting the world through the taste of a meal. Red, black, brown, golden, white, and even pink—together they form rainbow fields, each with its own flavor, aroma, and texture. These fields no longer belong to farmers alone. They are shared landscapes of culture and imagination.

Rice is more than food. It is a platform, a language, a world where ecology, art, and identity meet.