From freedom struggle to today’s politics, the story of India is also a story of men, power, and women’s rights.

In 1947 India became independent after 200 years of British rule. The freedom was hard-won: hundreds of thousands of women and men across the country fought at different levels to ensure the end of British rule. The promise independent India held for its people was one of equality of genders, classes, castes, religions.

A significant part of the battle for independence was fought on issues to do with women and women’s bodies. For the British, the fact that India had several customs, practices, traditions that were in their eyes discriminatory towards women (such as child marriage, a ban on widow remarriage and so on) became an excuse for targeting Indian men as ‘effeminate’ and ‘emasculated’ and ‘not man enough’ to rule their country.

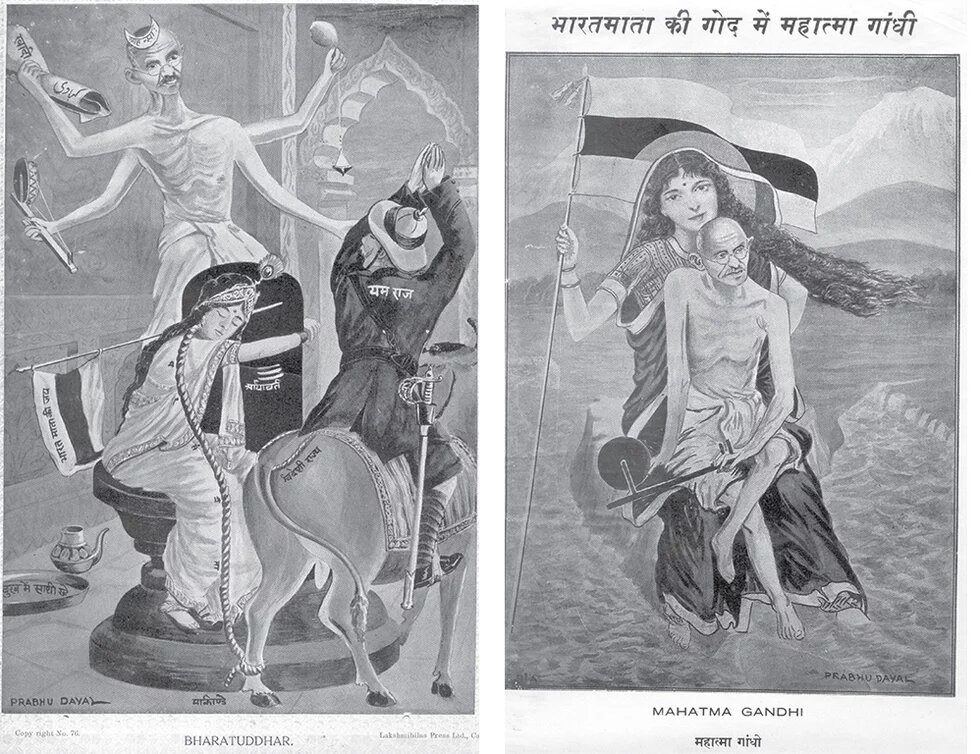

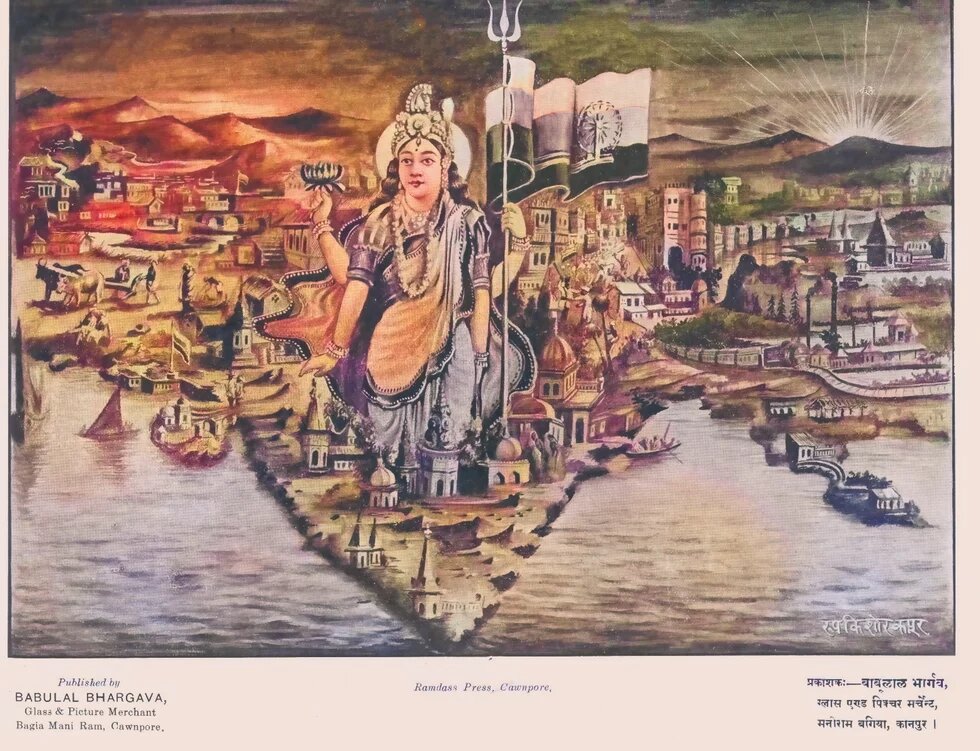

The Nation as Mother: Protectors and Worshippers

Indian men responded to these assumptions in different ways: one of these was to demonstrate how valued women, femininity, motherhood, were in India. Thus, the nation was imagined as the mother, to be worshipped as pure in body and soul, and to be protected from defilation and desecration by the foreign ruler. It was therefore the Indian man’s familial and national duty to protect not only Mother India but all women, mothers, sisters, daughters. Protection needed strength, of character and body. This discourse found powerful resonance in popular understanding and the image of the mother as goddess, mapped onto the country became commonplace.

And yet, because the freedom struggle, led by Gandhi, had been fought on the principle of non-violence, the expression of masculinity remained somewhat ‘quiet’. But across India, another kind of masculinity was brewing. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, a deeply conservative, right wing organization, rejected Gandhi’s non-violent doctrine and began to train their members to guard and protect the motherland, and to use violence to do so if needed. A new masculinity, fuelled by strict discipline, and rigorous training, began to take shape. In this, men were strong, warriors, the guardians of Mother India and its daughters, wives, sisters.

This burgeoning masculinist nationalist discourse faced a severe challenge at the very moment it was in the ascendant as the British administered what came to be known as their ‘parting kick’ – dividing India into two countries, India and Pakistan, on the basis of religion. Pakistan became the country for Muslims and India, supposedly for all religions but in effect largely Hindu because of its majority Hindu population.

Violence and Women’s Bodies: What Price Masculinity?

The Partition, as it came to be known, was characterized by unprecedented violence as people, who had thus far lived in relative peace, albeit with their differences, began to flee to places where they felt they would be safer with their own kind. Almost overnight, Hindus, Muslims and others were forced to abandon homes they had lived in for generations and to flee, sometimes with only the clothes on their backs, to the ‘new’ country, leaving behind properties, friends, connections. Arson, loot, murder, rape, became the order of the day.

Women were particularly vulnerable and some 100,000 of them are believed to have been raped, often abducted, some sold into slavery and some coercively married, by men of the other religion and sometimes, using the mayhem of the moment, even by men of their own religion.

A New Enemy: The Discourse Shifts

The masculinist discourse began to shift. The British had gone, Indian men could no longer claim they were protecting Mother India. The country was theirs, and yet, women were still being violated. Now, the enemy became the ‘other’, the Muslim male, and the Hindu male once again had to prove his masculinity. Muslim men began to be seen as the aggressors, predatory males on the lookout for vulnerable Hindu women, ready to lure them into all kinds of false relationships. Their so-called ‘aggression’ was linked to what was said to be Muslim men’s insatiable sex-drive, their libido, and to the fact that they ate meat, in particular beef. A new national enemy began to take shape.

Women Take the Initiative

Even as this was happening, India’s women were working hard to secure rights for women in the new India – they sought not protection, but rights, citizenship, opportunities. They formed their own organizations, they helped shape the framing of the Indian Constitution, they created institutions, they fought against rising prices and at all times they foregrounded the Indian woman as a rights bearing citizen with agency.

As a result of their efforts new laws were put in place, more and more women began to step out to vote – such that today in India the number of women voters slightly exceeds that of men – a dynamic women’s movement took to the streets to hold the State to account on its promises. For a while then, the assertion of nationalist masculinities seemed to take a backseat although it never really disappeared.

The Politicization of Religion

From the nineteen eighties on, a series of political developments resulted in foregrounding, once again, the Hindu-Muslim divide, and right-wing political parties began to make their mark on the political horizon. Hindu-Muslim tensions surfaced, Muslims again became the target of violence, attack, accusation. And the full-blown assertion of Hindu masculinity began to be visible with the decisive victory of the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP), a far-right party that holds power to this day and whose vision of India sees the country not as a modern, secular nation but as a Hindu nation. The party’s linking of masculinity to the nation came full circle when they chose the god Ram, generally seen as a man torn between love for his wife and duty towards his subjects, as their symbol and recast him into a warrior.

…And the Return of Protection

The discourse on the protection of women returned and this time, it entered the private sphere too. Hindu-Muslim marriages began to be viewed with suspicion. No matter that the two people within a marriage were adults and had chosen to be in a relationship, they were coercively separated, often by vigilante groups who saw themselves as the guardians of the morality of their women and the nation.

Muslim men were accused of ‘love jihad’ – a move designed to seduce ‘innocent’ Hindu women and lure them into relationships on the pretext of offering love and marriage. In one place women drinking in a bar with their friends were pulled out and beaten by ‘Hindu’ groups who accused them of being women of loose morals and therefore ‘un-Indian’. The legitimizing of this discourse that infantilized women and refused to recognize them as equal citizens, occurred at every level.

In different parts of the country, political leaders rolled out ‘welfare’ schemes and sops for women: soft loans, gas connections, help with housing, free toilets. While all of this did make some difference to women’s lives, it was also something that once again reduced them to being recipients of male largesse, rather than equal citizens in a free country.

Rights, Agency, Hope and the Horizon for Change

Against this context, the battle for women’s rights has become harder. It does not make it any easier to know that this isn’t a development that is limited to India: across the world toxic masculinity is very much on display, whether it is in Russia’s attack on Ukraine. Israel’s genocide in Gaza, America’s assertion of its power and so on. Power, and male power, lie at the heart of this assertion and the dislodging of it will not be easy.

Where, then, does hope lie? in India, in recent years, queer and trans voices have become increasingly articulate and the community much more visible. The legal criminalization of aspects of their existence has been done away with. Queer communities no longer need to hide and pretend to be someone else, as the law recognizes their existence as legitimate and legal. Among them are also trans people, now recognized as the ‘third’ gender in India.

This opening up has led to the growth of a healthy literary and political culture in which discussions on masculinities and femininities occupy much more public space. With gender itself being destabilized, and with the coming in of the concept of the fluidity of gender identities, the needle has begun to shift. Moving between an ascribed identity and a chosen one has allowed for discussions on what masculinity means and why its toxic assertion is even necessary. Perhaps it is here that hope for change lies.