Kenya’s growing debt was long seen as a symptom of global financial dependence. But the bigger problem lies at home. Well-connected political elites dominate the domestic debt market and profit from a system they themselves created.

Kenya’s public debt profile is different from that of most fellow African countries in that it borrows more locally than it does abroad. Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs) are the largest bloc among Kenya’s leading domestic creditors, possessing unrestricted ability to influence the government’s borrowing plans.

By April 2025, Kenya’s total public debt was KSh11.49 trillion (US$89 billion), made up of external loans worth KSh5.326 trillion (US$41.286 billion) and KSh6.164 trillion (US$47.782 billion) domestic debt through Treasury Bills and Bonds. Most domestic debt is medium to long term (more than two years) but redemption challenges are apparent. The latest Treasury Medium-Term Debt Strategy report states that 18.6 per cent of the domestic debt fell due in June 2025 – about KSh97 billion (US$7.525 billion). Increasingly, the government is resorting to taking out new loans to repay older ones, both internationally and domestically.

By 2023-24, interest payments on domestic debt were double the interest paid on external loans – taxpayers paid KSh533.689 billion (US$4.13 billion) on domestic debt interest (70 per cent) while interest payments on foreign borrowings were KSh218.594 billion (US$1.6 billion) (30 per cent).

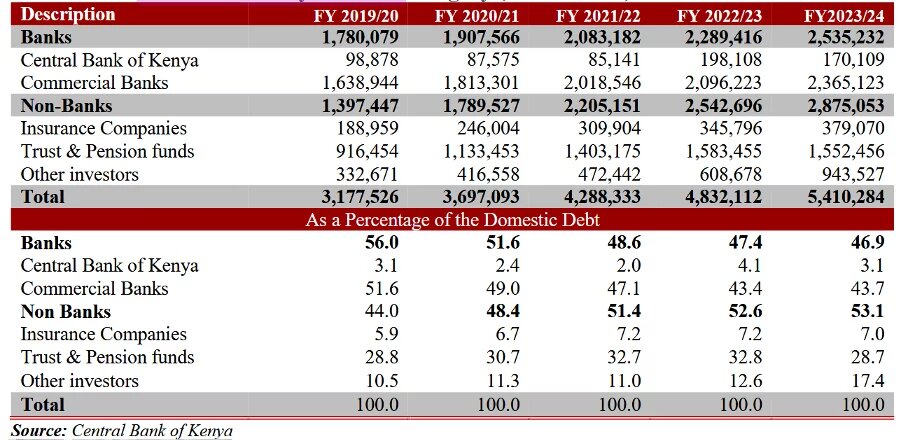

Domestic debt, the larger part of the national debt, is held by local elites through ownership of the banking and insurance sectors. As they hold half the domestic debt, it follows that they hold a quarter of the national debt. A year and a half ago, this was about KSh2.54 trillion (US$19.6 billion), equivalent to 15 per cent of nominal GDP in 2024. By the end of April 2025, domestic debt accounted for 53.6 per cent of the national debt of Kenya, with banks and insurance holding 49.6 per cent of this debt, equivalent to KSh3.06 trillion (US$23.7 billion). Kenya faces local bond maturities of KSh495 billion (US$3.84 billion) this year, rising to KSh822 billion (US$6.37 billion) next year.

Funding government internally is a goal worth pursuing but, in the Kenyan context of corruption and state capture, it is prudent to be inquisitive about who holds one quarter of the entire national debt in the form of government securities such as Treasury bills and bonds. This is particularly so as the official strategy is to increase the gross borrowing share of domestic debt relative to external debt to a ratio of 75:25 by 2028. Unlike the external public debt register where the names of the external creditors lending money to Kenya are disclosed, the identity of the creditors holding domestic government securities is not disclosed, the Central Bank (CBK) only disaggregates by the category to which the creditor belongs. (CBK releases domestic-debt tables every Friday in its weekly bulletin so that analysts can see auctions, maturities, and rollover risks within a week of occurring, but not the creditor’s name.)

Kenyans are generally unaware that Treasury bonds are unlawfully being used to finance recurrent government expenditure instead of development or capital expenditure. But, since 2019, there has been a recurring questioning of the identity of the creditors holding domestic debt. Combined with more recent campaigns to challenge the legality of Kenya’s domestic debt, with some going as far as to say that it is odious because the domestic loans are used to finance recurrent expenditure in violation of the law that requires the government to borrow only to finance specified development projects. They argue that Kenyan domestic debt is a decades-long illegal borrowing spree that offends the constitutional principle of intergenerational equity, leading us to this place, where the obvious question must be asked: cui bono?

That Kenyan banks prefer to finance government rather than the private sector is well documented. In 2024–2025, the Parliamentary Budget Office reports that private sector credit contracted (-1.1 per cent), while government borrowing grew (16.6 per cent). Despite a construction boom in and around Nairobi, by 2023, Kenyan banks had only 30,015 active mortgage loans on their books, with an outstanding balance of KSh281.5 billion (US$2.18 billion), a paltry figure considering that Kenyan banks hold government securities worth KSh2.365 trillion (US$18.3 billion).

No discussion about debt relief can be had in relation to Kenya without understanding the political economy of its banking and insurance sectors. At independence, all commercial banks and insurance companies were foreign-owned. Cooperative societies established savings societies before the government established state-owned banks in the 1970s just as it became clear that attempts to Africanise the commercial banking and insurance sector via employment were not successful, as the necessary workforce had yet to be trained.

A Presidential Commission ostensibly studying civil servants’ wages recommended the relaxation of conflict of interest rules to allow civil servants to enter the banking and insurance business, among others. Eponymously named after its chairman, the Head of Public Service, the Ndegwa Report of 1971 argued that the slow pace of Africanisation of the economy eight years after independence was because the best educated Africans were in public service, needlessly restricted from doing business by unsuitable conflict of interest rules. Henceforth, civil servants could do business (even with the government) and keep their public sector jobs.

Immediately, government drivers opened car repair workshops, education inspectors started private schools, doctors established private clinics, pharmacists in government employ began supplying medicine to the government; and senior civil servants in the Treasury, Central Bank and the Ministry of Economic Planning were offered and took up shareholding in the largely foreign commercial banking sector. By the 1980s, many in the last category of finance had incorporated or bought their own banks and insurance companies, even while officially in government as the regulator and policy-maker. After the Ndegwa Report, there was a spate of investor pools formed to buy shares in leading financial sector institutions in which politicians were invited to participate.

Kenya ended up with a domestic debt market that could fall prey to collusion between the policy side and the credit supply side. In a situation where monetary policy and interest rates are being set by a Central Bank whose chairman or governor has investments in commercial banks, Chinese walls become completely theoretical. Without much consequence, it is possible to influence the policy prescriptions and the regime that guides debt contracting at the domestic level. A leading Kenyan economist recently wrote:

“Whereas the bulk of this may be anecdotal, pertinent conclusions can be drawn from the relationships between senior management at the investment entities and the national treasury. Further, beneficial ownership details of these entities seem to reinforce this assertion due to the corresponding close relationship between the owners or at least their representatives and the top leadership of successive regimes over the years. As such, it is possible to plot the emergence of a particular policy in the context of the beneficiation of key investment entities and their big sway on the Kenyan economic landscape over time.”

The Cabinet Secretary for Finance and many other officials within the public finance management world have personal investments in government securities. The incentive to benefit from making certain policy decisions in such circumstances is obvious.

Today, the ownership of the 38 licenced commercial banks and 36 insurance companies is concentrated around a small group of individuals and companies, many of which are related to politically exposed persons, past and present. Publicly traded companies are required to list their top shareholders in annual reports, so it is easy to prove the shareholding of the families or heirs of three of Kenya’s five presidents, several former permanent secretaries of the Treasury, at least two governors of the central bank, the longest serving attorney general, at least three heads of the civil service, CEOs of state-owned enterprises, police and military chiefs, and parliamentarians past and present.

These Kenyan PEPs took control of the banking and insurance sectors long before the term PEP existed. They constitute an obvious starting point for anyone seeking to identify systemic vulnerability to macro-critical corruption.

Share of Domestic Debt held by Banks and Insurance Companies

(US$1 = KSh129)

The views and analyses expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Heinrich Böll Foundation.