High debt and climate vulnerability reinforce each other. Yet with targeted relief and reforms, Africa could break this vicious cycle and enter a positive cycle of green growth.

Africa holds extraordinary promise for sustainable development. With 60 per cent of global solar potential, 30 per cent of transition mineral reserves, and vast wind energy capacity, the continent could lead the global green transition. Its young, rapidly growing population – expected to reach 2.5 billion by 2050 – adds further momentum. Yet this promise is under threat.

The continent is on the frontline of the climate crisis. Seventeen of the twenty most climate-vulnerable countries are African, despite contributing less than 4 per cent of global emissions. Floods in Kinshasa and Cape Town, heatwaves in South Sudan, and prolonged droughts in the Horn of Africa show that climate change is no longer a distant risk but a present emergency.

At the same time, unsustainable debt is draining African budgets. Public external debt has more than tripled since 2008, with a growing share owed to private bondholders. Rising global borrowing costs and weakening African currencies against the US dollar have increased the burden. Between 2021 and 2023, sub-Saharan African countries paid over twice as much in external debt service as they received in climate finance. Actual climate finance inflows – just US$35 million – remain far below the US$143 million required annually to meet adaptation and resilience goals. In 2024, interest payments consumed more than 10 per cent of government revenues in 27 African countries, exceeding spending on health or education. This imbalance fuels a vicious cycle: climate shocks undermine growth, debt service drains public resources, and too little remains for urgently needed climate adaptation and resilience.

The pain of this debt burden has been worsened by increases in global borrowing costs and a continued decline in African currencies against the US dollar. Between 2021 and 2023, countries in Sub-Saharan Africa paid more than twice as much in external debt service as they received in climate finance during the same period. This is despite the fact that actual climate finance inflows, at US$35 million, fall far short of the actual annual requirement of US$143 million needed to meet adaptation and resilience targets. In 27 countries on the continent interest payments exceeded 10 per cent of government revenues in 2024, leading them to spend more on interest payments than on health or education. This imbalance creates a vicious cycle: climate shocks undermine growth, debt service consumes scarce resources, and little remains for investing in climate adaptation and resilience.

Structural inequities and external pressures

Africa’s debt dilemma is not just the result of fiscal mismanagement. It is also rooted in structural inequities in the global financial system. Sovereign borrowers across the continent face an “Africa premium”: paying far higher interest rates than countries with similar or worse credit histories. This persists despite Africa’s relatively low default rates. Financial flows are perversely reversed; according to the African Development Bank, more money is flowing out of African economies than coming in.

Borrowing is often unavoidable. Kenya, Malawi, and Mozambique have been forced to take on debt to rebuild after devastating floods and cyclones. Island nations like Mauritius must borrow simply to survive rising sea levels. Global shocks – from COVID-19 to inflation and soaring food and energy prices – have only deepened these vulnerabilities.

Cuts to foreign aid threaten to undermine essential services and slow recovery.

External pressures add further strain. Cuts to foreign aid threaten to undermine essential services and slow recovery. At the same time, new US tariffs imposed on African countries with trade surpluses risk slashing export revenues just when foreign exchange is most needed for debt repayments.

A growing call for change

Across Africa, leaders and experts are demanding a reset. At the 79th UN General Assembly in 2024, Nigeria’s President Bola Tinubu urged “comprehensive debt relief measures, to enable sustainable financing for development”, warning that without concessions, “meaningful economic progress in developing nations will remain a distant dream”. Kenya’s President William Ruto has called the global financial system “unjust” and in need of a complete overhaul.

Former Kenyan central bank governor Patrick Njoroge was even more direct in a recent interview: “The debtors and the creditors need to get together and come up with a sort of debt relief arrangement for the highly indebted countries. Otherwise, the downward spiral will only continue.”

Former African heads of state have launched the African Leaders Debt Relief Initiative (ALDRI), backed by South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa, demanding large-scale relief with participation from all creditors and lower borrowing costs. Pope Francis’s Jubilee Commission adds moral weight, calling for a new beginning for countries suffocated by debt.

Momentum is also evident institutionally. The African Union’s first continental Conference on Debt in May 2025 called for a UN Framework Convention on Sovereign Debt, climate-sensitive debt assessments, and expansion of the Common Framework.

Making debt work: A shared responsibility

While the global financial system must change, African countries also need to strengthen debt management, improve transparency, and mobilise more domestic resources. Debt relief will only be credible if the freed fiscal space is directed toward climate adaptation, education, health, and inclusive growth.

While the global financial system must change, African countries also need to strengthen debt management, improve transparency, and mobilise more domestic resources.

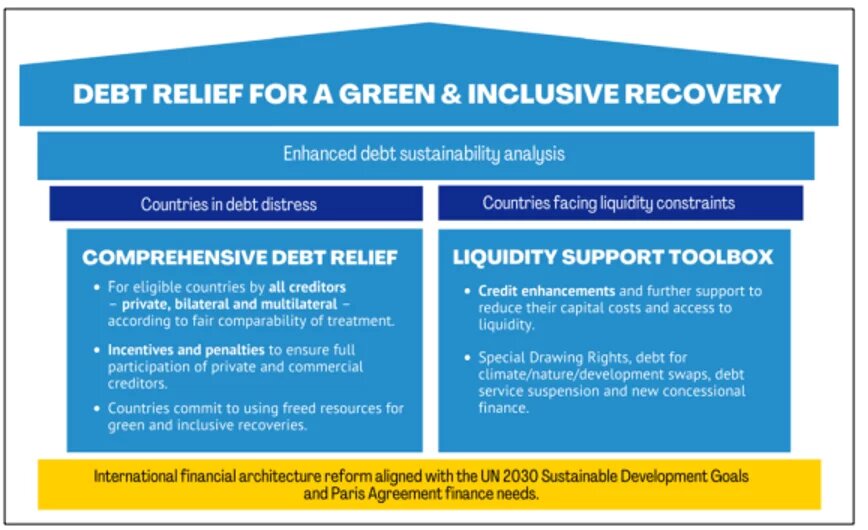

The Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) proposal provides a roadmap. Its bedrock is a comprehensive and speedy reform of the debt sustainability analysis to incorporate climate risks and critical investment needs for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and climate targets, as shown in Figure 1. For distressed countries, it calls for comprehensive restructuring, with all creditors at the table based on fair comparability of treatment rules. In return, countries must commit to utilising the freed fiscal resources for green and inclusive development and adhere to enhanced public debt standards. For countries facing liquidity pressures, it recommends concessional finance, debt-for-climate swaps, and credit enhancements.

Figure 1: Two pillars for debt relief for a green and inclusive recovery

Source: Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (2025)

From Vicious cycle to positive green growth

High debt and climate vulnerability currently reinforce each other in a downward spiral. But with meaningful relief and reform, Africa could instead enter a positive cycle of green growth: freed fiscal space would finance resilience and clean energy, boosting growth, strengthening debt sustainability, and attracting new investment.

Figure 2: The positive cycle of green growth

Source: Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (2024)

As Joyce Banda, former President of Malawi and member of ALDRI, put it: “What is being sought is debt relief, not charity… A strong Africa means a stronger world. Unlocking Africa’s economic potential will drive global growth, strengthen supply chains, and accelerate the green transition.”

To start, the G20 should agree on measures such as automatic debt standstills during restructuring, expansion of the Common Framework to middle-income countries, and debt sustainability assessments that fully account for climate risks and development needs.

The choice is stark. Africa’s debt and climate crises are inseparable. Tackling them together through ambitious relief, systemic reform, and stronger governance at home is not charity – it is an investment in global stability and green growth. Failure to act will trap millions in poverty and weaken the world’s fight against climate change.

Sarah Ribbert writes regularly for the Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) project. More of her work can be found here.