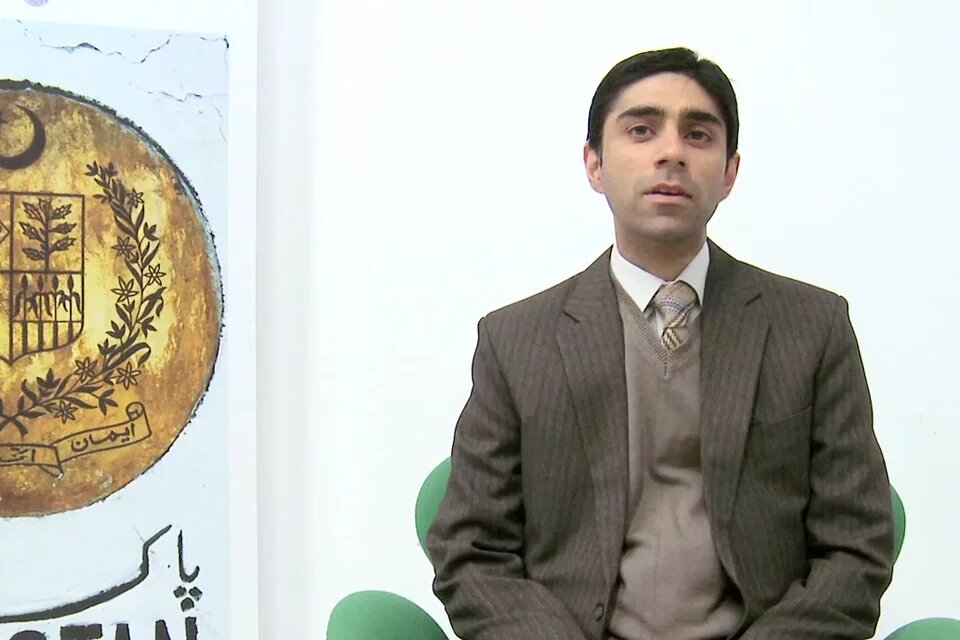

Heinrich Böll Foundation: Mr. Moeed Yusuf, you are the director of the South Asia programs at the U.S. Institute of Peace and have been engaged in expanding the institute’s work on Pakistan/South Asia since 2010. Your current research focuses on youth and democratic institutions in Pakistan, policy options to mitigate militancy in Pakistan and the South Asian region in general, and the U.S. role in South Asian crisis management. And you have been widely published in national and international journals, professional publications and magazines. Today we would especially like to talk about the publication Getting it Right in Afghanistan, in which you were a co-editor. Would you please be so kind and give us a summary introduction?

Moeed Yusuf: It’s a fairly disturbing summary that I am going to give you. Essentially, this book compiles a lot of work from the past 5 or 6 years that the U.S. Institute of Peace has done in Afghanistan and Pakistan on the political settlement in Afghanistan and the regional angle of that settlement. The conclusion we draw, quite honestly, is that even things that were written 5 to 7 years ago remain entirely relevant today. So in some ways, a lot has changed in Afghanistan; in other ways, when it comes to political settlement and the peace process, not much has changed at all. We have put together a host of literature that we produced previously to suggest that reconciliation in the peace process remains difficult, but the solutions are very well known. It’s about trying to make sure that we can get to them and that’s where we have failed so far.

hbs: Why did you and the other authors decide to discuss the political settlement process in this particular way?

Yusuf: We believe that unless you get to a political settlement in Afghanistan, no matter what changes you can bring, peace will still be very tenuous. The elections and the security transition are both crucial elements, but ultimately, unless you get a political peace settlement along with the political transition in the elections, it’s very difficult to see how the insurgency will end and peace will come to Afghanistan.

hbs: Who are the drivers of the insurgency at the regional level?

Yusuf: I think fundamentally, the Afghan insurgency is an internal phenomenon. The regional actors have exacerbated the problem in some ways. Some have tried to mitigate it, given their own interests, but to say that the Afghan insurgency originates outside of Afghanistan is a bit of a stretch. I would argue that countries, all countries, have operated in self-interest. A lot of times they haven’t helped the cause of peace in Afghanistan. You can talk about Pakistan, Iran, the Central Asian republics, virtually all the neighbors, but the real problems lie inside of Afghanistan.

hbs: What could be the drivers of this settlement process?

Yusuf: There are a number of them. There is governance; bad governance is certainly one. The fact that the Taliban feel that they are part of the political process in Afghanistan rather than an insurgent force is another. Then there are spoilers, the extremists, Al-Qaida, other Central Asian actors that are present in the Pakistani bordering regions and in Afghanistan. They are certainly a problem. And then some would argue that foreign troop presence has in some ways caused the insurgency to flourish even more and the extremists to use that messaging to push the government in Kabul further through violence. So there are a number of external drivers, but they are primarily internal.

hbs: How are the regional or neighboring countries involved in this process and what role do their particular agendas toward Afghanistan play?

Yusuf: I think Afghanistan, unfortunately for years, has been the proxy battle ground for its neighbors; not only its near neighbors, but also its far neighbors. There was the Soviet invasion and what played out in the 80s, and over the past 10-12 years, I think all the South Asian countries, Central Asian countries, and Iran, have all operated in self-interest. Sometimes they’ve helped the cause of democracy in Afghanistan, like the Bonn Agreement and Iran’s help in the beginning and Pakistan’s support to President Karzai through this process. On the other hand we have the sanctuaries in Pakistan, the alleged Iranian support to the Taliban, and the Central Asian republics playing their northern favorites over the southern ones. Everybody has really played their own game in Afghanistan, to Afghanistan’s detriment at the end of the day. Even if they have helped in some cases, I think it is a net negative at the end of the day for Afghanistan.

hbs: Speaking of the role of Pakistan towards Afghanistan, how are the relations between the two countries?

Yusuf: It’s schizophrenic. For years, Pakistan’s people to people relationship with Afghanistan has been very good, especially with the Pashtuns of Afghanistan. Remember that Pakistan has more Pashtuns than Afghanistan does, and Pashtuns are known to be in the majority in Afghanistan even though there has not been a census in a long time. So the people to people relationship has been very good, but the state-level relationship has always been dicey because Afghanistan was the last state to recognize Pakistan in the U.N. when Pakistan became independent. It still claims part of Pakistani territory in northwestern Pakistan. So there are a number of problems at the state-level, but ultimately, given the geography and the ethnic composition, there’s no way that these two countries can work without each other.

hbs: What are the changes that have taken place in Pakistan’s and Afghanistan’s relationship since the international intervention in Afghanistan?

Yusuf: A lot. Sometimes we don’t give credit to how much have changed, at least in urban Afghanistan. There has been a ton of development; a lot of work has gone in that is in my mind irreversible. The Afghans are not going to give that up just because somebody wants them to. In the Pakistan-Afghanistan relationship, unfortunately there has been a lot of tension because Pakistan has been seen, sometimes unfairly, as the cause of all ills in Afghanistan. This is certainly an exaggeration, but the Kabul-Islamabad relationship has been very tense. It was quite a hostile relationship some years ago, and although it has improved, tensions still remain.

hbs: Coming back to the times since the elections in Pakistan in 2013 and the Nawaz government taking charge, what has changed since then?

Yusuf: I think nothing was changed by the change of government in Pakistan, but given the circumstances in Afghanistan, I feel that Kabul, Islamabad and the Western countries are now coming closer to each other’s view point. The view point is that no military victory is possible in Afghanistan, so political reconciliation is crucial. The elections and a smooth transition are crucial and the ANSF funding remains very crucial for the future of Afghanistan. Finally, Pakistan has now formally said that it does not want America and NATO troops to pull out completely and leave Afghanistan behind. So I think at the broad level, there is convergence that you’ll have to find all these compromises. The problem is that I don’t think anybody knows how to make that happen. That’s where the real problem lies right now.

hbs: What policy interest does and should Pakistan have?

Yusuf: The bottom line, despite all the troubles that Pakistan and Afghanistan have had, is that they understand that they are locked in at the hip. The geography does not allow them to operate separately. Afghanistan is land locked. I’ve already talked about the Pashtun element. So the fall out of any real instability in Afghanistan, will land on Pakistan. Where they come together completely on the policy issue is that Afghanistan must stabilize. Pakistan has no appetite for fresh inflows of Afghan refugees as it did in the 80s. The economic costs were very high then and they’ll be higher now. Ultimately, both of them know that they have to get Afghanistan to peace. The problem is how Pakistan thinks it should get there has not been the same as how Kabul and the international community think they should get there.

hbs: What are the differences on how Pakistan and the international community look on this?

Yusuf: Well, Pakistan has been much more focused on this reconciliation piece. Because of the sanctuaries in Pakistan, Pakistan’s number one effort has been to get the Taliban back into Afghanistan through a political deal. I think the international community and definitely actors in Kabul were very hesitant about letting that happen, until very recently when it became clear that the international community is pulling out and a military victory has not come about. The idea of the troop surge was ultimately to degrade the Taliban. Pakistan was never on board with this. It wanted a political reconciliation without pushing the surge to the point where military victory would take place because this might mean the Taliban would actually not go back to Afghanistan and this would hurt Pakistan’s goal of taking on its own Taliban factions and daming them ultimately.

hbs: How do those interest match with the Afghan government’s interests and expectations towards Pakistan?

Yusuf: As far as stability is concerned, they are on the same page. How to get there is the question. One of the Pakistan’s policy flaws over the years in Afghanistan is that it has been narrowly focused on picking favorites within the Pashtuns of Afghanistan. This policy hasn’t been broadened to non-Pashtun elements, the erstwhile Northern Alliance. A lot of the government in Kabul has actors that belong to the erstwhile Northern Alliance, so that tension has remained. Pakistan has reached out over the past year or two, but the steps taken have been very modest. So I think that is one level of tension. Second, if I may say so, I think there has been a fare bit of conscious and deliberate effort on the part of actors in Kabul to portray Pakistan as the number one reason for problems in Afghanistan, which I think is factually incorrect. Pakistan definitely has not done enough to tame the presence and inflow of insurgents from its territory into Afghanistan, but if somebody were to say that if Pakistan stopped this, then Afghanistan would become peaceful, I think that is going too far.

hbs: How far were the real issues of conflict actually addressed in the recent talks between the two countries’ elected leadership?

Yusuf: I think the focus recently has been on two transitions: the political transition and the security transition. Politically, Pakistan wants the elections to go well so that Afghanistan does not fall into chaos. It wants to help in the peace process following that, although I will say that I think we often exaggerate the influence that Pakistan has on the Taliban. I don’t know how much it will be able to do but it wants to try. And then it’s also desperate to make sure that the international community continues to put in resources, material resources into Afghanistan because we saw the Najibullah government fall as soon as the Soviets pulled out their financial support and nobody wants to see that happen again.

hbs: What are the institutional arrangements made in both countries - or particularly in Pakistan - to bring forward political discussions and negotiations about economic development?

Yusuf: Well, they have trade agreements of course. They now also have a transit trade agreement, which is not very functional right now because Pakistan is hesitant to let overland rights be given to India. There is the Afghan transit trade, which has stayed on for a long time. Afghanistan is now Pakistan’s third largest export destination, so a lot of things have moved on the economic front. The problem is that as soon as the security aspect comes into it, the economic ones get wiped away because the tensions rise again over the Taliban and the insurgency. Where I think they really need to focus now, more than trade, is investment and energy. The real potential is collaboration on energy for regional benefits, be it through pipelines, be it through electricity transmission, or through any other means, but energy to me has a real potential to tying these countries together in a way that they cannot afford to have tense relations in the future.

hbs: Could you elaborate a little bit more on the energy sector and also on the meaning of the water management in the region?

Yusuf: On energy, there are a number of plans: you have the CASA-1000, a plan for electricity transmission lines to be laid, which is happening as we speak. There is the TAPI pipeline, the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India Pipeline, and there are a number of other thoughts on trying to flow energy through Central Asia into Afghanistan and into Pakistan. All of these I think are great ideas. How do you make them operational? The number one problem there, even more so than investment, is security. Unless Afghanistan achieves some level of stability, and as long as Pakistan’s Balochistan is in a state of unrest, it will be very difficult to get these very massive pipelines coming through. I think this is futuristic, but if you were to find a silver bullet for these two countries to get along well and for the region to prosper, I think absolutely it would be energy.

In terms of the water treaty, my own view is that I think water is an issue, but it’s not nearly as big of an issue as it has been made out to be. I think in the future both countries are going to be water stressed, the whole region is going to be water stressed. I’m all for the treaty, but to say that this should now become the mainstay to show that Pakistan and Afghan relations are now improving is not enough. We need to go to larger investment issues, to energy issues and to other bigger problems.

hbs: Is there any chance for a win-win situation for both countries?

Yusuf: I think this year is crucial. If you can find political, economic and security transitions in Afghanistan that keep the country peaceful, that keep the country from falling into chaos, I think you’ve got a real opportunity there. If things start going wrong in Afghanistan, then you will find much more hedging from Pakistan, much more support to the actors it prefers, much less willingness to take Afghan refugees and all sorts of tensions that come with it. So really right now, all the eggs are in the basket of the Afghan transitions and I’m cautiously optimistic because Pakistan, Afghanistan, the U.S., and the international community seem to be on the same page on what they want. Whether they can pull it off, whether the Taliban can be persuaded to join the political process remains to be seen.