It has become so quotidian as to be second-nature: walking down a city street, something captures your eye – a piece of art, a street protest, the sunlight through the trees. You pull your smartphone from your pocket, snap a photo or short video, and open your social media platform of choice and send it to “the cloud.” The content is whisked away, and in an instant it is available for others to see and experience, comment on and recirculate. It happens in the blink of an eye, in an ethereal, disembodied flow that seems to belie any material or human intervention whatsoever.

You are at home, surfing your favorite social media platforms, catching up on posts from friends and looking at the latest videos uploaded by users known and unknown to you. Suddenly, you find yourself witnessing a video of a violent act being perpetrated on what appears to be a child. The video starts playing as soon as you scroll to it. You are shocked, taken aback, and you quickly look around to make sure your young son is not in the room with you. You rush to find the button to stop the playback, even though you’ve seen and heard enough to disturb you for the rest of the night. You find a place where you can “flag” the content and you are taken into a reporting window, where you navigate a series of menus allowing you to report the video as problematic. Once you do so, you are reassured that it will be reviewed, somehow, and you return to your surfing. The video is gone, but your feelings of unease remain. What have you just witnessed, and why?

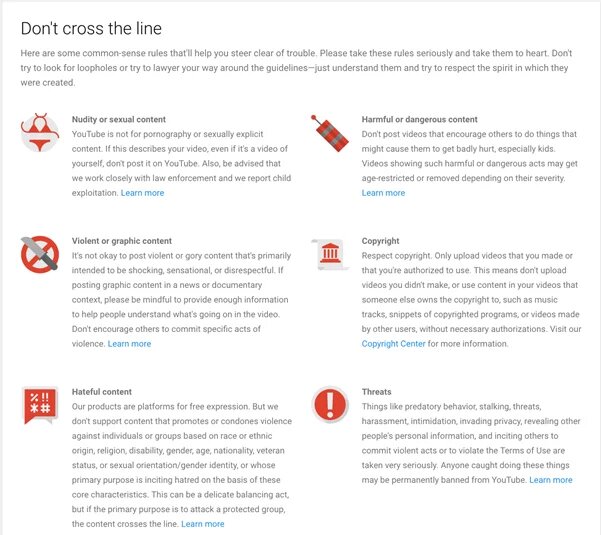

A few days after you captured that street protest, a political street demo in which anti-immigrant protestors shouted epithets at a crowd, you receive a notice in your email of a “takedown.” It explains to you that your videos or images have violated site policy and have been determined to be inappropriate. You realize that you never before had reviewed these policies, but you follow a link that explains that nudity, hate speech and violence are not allowed. Who made the complaint? And who judged your uploads against these criteria? Just what constitutes hate speech, anyway, and does it differ whether you are in Berlin or Boston?

Welcome to the world of commercial content moderation, or CCM, one of the thorniest, most complex and most controversial aspects of today’s social media ecosystem. Despite its centrality to ongoing maintenance of social media platforms and sites, CCM is one of the most unknown and little understood implications of the widespread global adoption of social media platforms as a part of everyday life. While the major social media firms of Silicon Valley have gone to great pains to paint engagement with social media platforms as fun, leisurely, harmless and without material or human consequence, CCM is a process that is almost completely reliant on the computational engine of the human mind – one that, at this time, cannot be adequately replicated by machines or algorithms at any kind of large scale or in a cost-effective means. While some of the more simple-to-find violations can be automated (think: racist slurs in a text comment or copyright material that can be matched, bit for bit, to a copy in a library for this purpose), typically it falls to human eyes and minds to complete these tasks. Yet if one stops at all to think about the process of how photos, videos and comments (“user-generated content,” or UGC, in industry parlance) are circulated around the globe at all, one is more likely suspect that any processes involved are mechanized, computerized and likely driven by algorithms and not real people, dispersed around the world. And because of the sheer amount of material uploaded to platforms and sites each minute, hour and day, most material that enters a CCM worker’s queue is there because a user – someone like you or me – has alerted the platform to a problem after viewing or experiencing the image or video.

In the course of CCM work, the moderators who undertake it look at thousands of images, videos, profiles and comments day in and day out, adjudicating them against the community standards and user policies of a site, as well as local pertinent regulations and laws that govern what is or is not acceptable. They also are called upon to invoke their own sense of taste, to the extent that they match that standard as set by the firm for which they are moderating. They perform these complex tasks in a matter of seconds, during which they are exposed to the same kind of content that might shock, disturb, frighten or sicken the average social media user.

Unlike the coders and engineers who are often imagined when the general public thinks about social media workers, CCM workers’ conditions are often much less glamorous. Distributed around the globe, both in order to manage the 24/7/365 nature of social media platforms, as well as to take advantage of less expensive labor markets in certain regions and countries, CCM workers often work at arm’s length from the platforms for which they moderate. Even when CCM workers are located onsite at the headquarters of a platform in Silicon Valley, those workers are likely contractors, working for a third-party company at one to several levels removed from the platform itself. In this way, the status of the workers and the work they do is less valued (literally, in terms of remuneration, and figuratively, in terms of status accorded it) than those of their peers in the social media industry. In the US, in particular, this can have serious repercussions, as access to adequate health and medical care is often directly tied to employment, and contracting companies may elect to not offer it to their employees – who are exposed to graphic content as a direct function of their job duties - at all.

In other cases, CCM workers might be many thousands of miles and culturally far removed from the users whose material they screen. CCM work is undertaken in many sites around the globe, from Romania to Ireland to India to the Philippines, as well as in places like Iowa in the Midwest of the United States. Wherever they are located, CCM workers are trained by companies must to embody the values, tastes and judgments of the audience they imagine they are serving. In some cases, this can lead to significant gaffes, such as numerous takedown on Facebook of breastfeeding mothers or one recent case of a father cradling his sick son in the shower that Facebook also removed. Meanwhile, Facebook has vacillated on its policy towards other kinds of clearly violent content, such as videos of beheadings, but typically errs on the side of allowing such material when it believes it serves a newsworthy purpose. This issue has come to the fore as platforms such as Facebook and others have begun auto-playing videos, leading to many users being horrified by being exposed to the graphic murder of another human being without having been asked to make a choice and when images of loving parents, such as breastfeeding mothers, are removed.

Most major social media sites and platforms view CCM work as a critical function of the social media production process. Not only might the circulation of a shocking video cause widespread user discontent and complaints, but it could, in some cases, expose the firms to liability for having hosted it. In spite of this, CCM workers tend to be out of sight, precluded from talking about their work by non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), and poorly paid relative to others in the industry. It is the unglamorous underbelly of social media sharing. Few firms will discuss the existence of these workers openly, and certainly will not expound upon their conditions and worklives.

My own research with CCM workers began in 2012, when I started interviewing and studying the worklives of CCM workers at a number of different sites and on a number of different platforms, with great difficulty, due to the secrecy that surrounds CCM practices. I have subsequently interviewed CCM workers in Silicon Valley at a major headquarters of one of the most important global internet and social media firms, content moderators on digital newspaper sites in the US, and CCM workers contracting in Manila, the Philippines, for a major dating app and site. While each situation and case varied, this highly diverse group of workers shared a number of features in common, including their desire to use the CCM job as a stepping stone out of what one described as the “cesspool” of the internet and into better work, their relatively paltry pay as compared to others in the tech industry and vis-à-vis the conditions and content to which they were exposed on a daily basis, their sense of altruism in that they felt they were sparing others from seeing the material that they had to see – and often could not unsee, and their sophistication and understanding of the importance of the work they did and the lack of value assigned to it. Most recently, Berlin-based theater director and documentary film producer Moritz Riesewieck has followed this thread, traveling to Manila to track down and document the stories of CCM workers there, most of whom wanted to appear in the shadows in order to protect their anonymity and to describe their experiences viewing horrible content.

In the meantime, the social media industry faces a growing problem. The amount of content posted to social media platforms and sites shows no sign of abating. Billions of users now sign on to platforms and sites each day, and this ease of participation is facilitated by the proliferation of smartphones, which provide extremely powerful cameras and the means to which to distribute their outputs. Meanwhile, governments are demanding more of the social media platforms that frequently operate on a borderless model and yet follow both the laws and social mores that may not be globally translatable. In Germany, politicians are wrestling with stringent anti-xenophobia laws that prohibit hate speech targeting ethnic minorities and other groups, and have attempted to enlist the cooperation of a number of major U.S.-based platforms, such as Facebook, Google and Twitter. As much of the efforts are concentrated towards eliminating this hate speech, illegal under German law and a particularly sensitive topic in the German context, as it manifests online, the solution (so to speak) is clear: it will fall to the efforts of CCM workers who are steeped in the particulars of the German context to manage digital content that flows from all corners of the world into German territory. The problem will be highly labor-intensive, expensive and technologically challenging for the firms to address. And to date, it is not immediately clear whether the actions the firms have already taken have been adequate, despite commitments from Facebook CEO to tackle the issue by opening a Facebook office in Berlin in early 2016.

Even if firms managed to completely cull their sites of violent videos and racist, xenophobic hate speech, the issue does not stop there. Free speech advocates, such as the Pirate Party, complain that efforts to curb such speech amounts to little more than censorship, and their libertarian ethos puts them at odds with such efforts. And the removal of such content does very little to address what, to me, seems like a much more significant and compelling problem: the impetus to create and then circulate images and videos that showcase harm to others. Despite the best efforts of CCM workers, they will be the first to tell you that the flow of content for them to remove has not slowed down. That is the fact that may be the most disturbing of all.

To learn more about CCM:

See the videos of Mortiz Riesewieck, Sarah T. Roberts and others at Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung performing a creative piece about and discussing CCM.

Part 1: Die Müllabfuhr im Internet - Lecture Performance

Part 2: Die Müllabfuhr im Internet - Vortrag & Diskussion