Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi decided to stake everything on the referendum: his personal credibility and his political legitimacy. His failure leads us to the question what kind of change Renzi was actually representing.

On 4th December, for the third time in the history of the Italian Republic, Italian citizens were asked to bring out their vote on a constitutional reform. For the second time, their response was negative. Nevertheless, last Sunday’s referendum was fundamentally different from the previous ones, for several reasons, which makes the analysis rather complex.

First of all, with 68,48 percent the participation rate was astonishingly high, both with respect to previous constitutional referendums (34,05 percent in 2001 and 52,46 percent in 2006) and also compared to the recent European election in 2014 (58,69 percent). This is surely an important signal for the ‘health’ of our democracy, which had been eroded by an alternation of ‘technical governments’ and government reshufflings. It underlines the desire of people to be part of the political debate, especially when relevant topics such as the constitution are on the table.

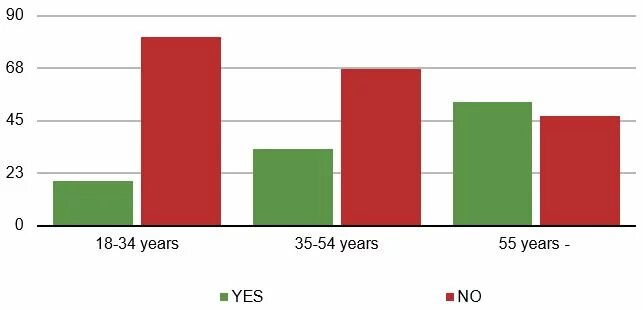

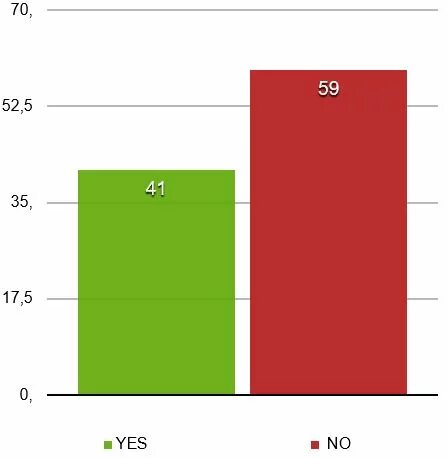

Secondly, there is the result itself: 59,11 percent of Italians voted ‘No’ against 40,89 percent voting ‘yes’ ─ so, clearly, the difference of almost 19 percentage points does not leave space for any doubts or second thoughts.

Thirdly, what cannot be underestimated is the heterogeneity within the two different camps. Indeed, during the last months we were spectators of many debates on public media, which often turned into battles between the ‘new and the old’, ‘movement’ and ‘immobility’, ‘the future’ and ‘the past’.

On the one hand, there was Renzi and his coalition of centre-left and centre-right parties; on the other hand, a diverse group made up of antifascist partisans, trade unions, constitutionalists, radical left movements, Lega, Forza Italia and the 5 Star Movement. The convergence of extremely different political positions and the temporary closeness of various political groups on this topic was something completely new for the country. Obviously, behind this ‘muddle’, as the opposition was contemptuously named by Renzi, there were noble and less noble political motives An example for the latter is, typically, Berlusconi who became a ‘No’ supporter after having signed an agreement on structural reforms (Patto of Nazareno) with Renzi in 2014.

However, among the common people, the so called silent majority of the country, there was a vital desire to discuss about the reform and to clearly understand what the possible changes would mean. In this sense, the last weeks were a prolific and vivid period, not remotely resembling the dangerous upsurge of populism envisaged by national and international media. Civil society was able to reconquer its own space, through the organisation of public events, seminars at schools and universities, or simply through discussions at work, on the streets and with friends.

Renzi and the failure of the politics of sloganeering

Renzi’s reform proposal with its modification of 43 articles stood for a radical change of the constitution. Among the most controversial points, there was the new composition of the Senate, where 95 mayors and regional councilors should replace the 315 senators directly elected by citizens, increasing the risk of conflicts of competences between State, regions and parliamentary bodies; the centralization of power with respect to local autonomies; an increase of the number of legislative procedures and the rise of the threshold of numbers of signatures needed in order to hold a referendum to approve a law proposed by citizens.

Moreover, the idea of combining a new electoral law, ‘Italicum’, and a constitutional reform was considered by many as an authoritative imposition, even if covered with the veil of a ‘necessary change’. In fact, the electoral law, approved by the Parliament in May 2015 and now under examination by the Constitutional Court because of elements of potential unconstitutionality, was already assuming the constitutional reform to be aproved.

As soon as the consensus on the referendum shrank, Renzi decided to stake everything on the referendum: his personal credibility and his political legitimacy. He attempted to put the alleged stability of his government and the core norms of a nation on the same level. This was probably his biggest mistake. Renzi thought he could impose his personal vision of the country and tried to exploit the widespread sense of stagnation and disaffection with politics.

Renzi was able to do what even right wing governments were unable to achieve

He eventually turned the referendum into a judgment on his government, believing this would help him to win. Indeed, if there was a judgment on his work, this was certainly not positive. Consistent with his intention, Renzi declared his will to resign as soon as the results were official, but fact is that his government will remain in charge until the approval of the budget law, as requested by the President of Republic on December 5th.

If we look at the regional distribution of the votes, it is interesting to see that ‘Yes’ reached the majority only in Emilia Romagna, Toscana and Trentino Alto Adige, whereas ’No’ won in all the southern regions and also reached the 63,32 percent of votes in Lazio. Particularly interesting is the result in the southern regions (all governed by Renzi’s Democratic Party), where Renzi attempted to collect votes and gain support through several visits during the last weeks. Moreover, if we link the regional outcomes with the first provisional data on the age composition of the vote, we get further interesting insights. It shows that young people, the ones who should represent the ‘new’ according to the rhetoric of Renzi, have been the strongest opponents of the reform.

This leads us to the question what kind of change and innovation Renzi was actually proposing and representing. To start with his labour market reform, the so called Jobs Act: here Renzi was able to do what even right wing governments were unable to achieve: the abolition of the right of new workers to be reintegrated in case of unfair firing (the so called Art. 18 of Statuto dei Lavoratori). At the same time, a system of fiscal incentives was established in order to encourage firms to hire new workers.

‘Hourly labour costs below the eurozone average’

However, it turned out that many firms were actually converting old temporary works into new ‘permanent’ jobs in order to get the incentives, with the result that the net effect on employment growth was rather insignificant. A further deregulation in the labour market was introduced by this government with the liberalization of the voucher payment system. Initially created to regulate seasonal jobs and to fight the black labour market, vouchers are now massively used for a wide range of jobs and have significantly increased labour precarization.

Another milestone for Renzi’s government was the school reform, strongly contested by trade unions, teachers and students. Indeed, the so called ‘Buona Scuola’ reform, is now producing its effects in terms of chaotic misallocation of teachers across schools all over the country and obscure models of ‘dual education’, where the alternation of study and job experience for high school students has been introduced without the definition of the actual value of such experience. To illustrate this with an example: the Minister of Education recently signed an agreement with Mc Donald’s.

Even regarding universities and research, the government was not able to be the innovative force it pretended to be. A characteristic episode in this respect was the statement of the Minister of Labour Poletti, whose answer to researchers and PhD students asking for unemployment subsidies, that research does not constitute a job.

Consistent with this view, the guide ‘Why invest in Italy’ on the website of the Minister of Economic Development, states that one of the advantages of investing in our country is the presence of ‘hourly labour costs below the eurozone average’. What the pamphlet does not mention is that the source of this ‘cheap labour’ is not high productivity growth or technological investment, but essentially stagnant wages.

These examples show that Renzi, the leader of the biggest left-wing party of the country, was (and formally still is) running a government which embraces a neoliberal ideology, even if pretending to act for the wellbeing of the nation.

Very clearly, the dominant thought behind Renzi’s constitutional reform was to stress the necessity of ensuring higher levels of efficiency and flexibility of norms in order to guarantee quick decisions and a high reaction response to change. Many of these positions were echoing the words of J.P. Morgan, who in 2013 complained about the features of southern countries political systems such as ‘weak central states relative to regions; constitutional protection of labour rights;(….); and the right to protest if unwelcome changes are made to the political status quo.’

What the outcome of this referendum has shown is that the definition of rules and principles of coexistence and identity of a country cannot be based on a supposed criterion of efficiency.

The potential risks frightened the rest of the world much more than Italy itself

The Italian referendum was followed closely everywhere in Europe (and elsewhere) and the fear of a potential Italian exit from Europe or the eurozone was palpable. Yet, this scenario was and is unlikely. The fear of political instability of the government in case of a referendum rejection, and the potential risk for the stability of financial markets, which turned out to be highly overestimated, frightened the rest of the world much more than Italy itself.

What we Italians have learned from the fall of the Berlusconi government and the succession of the three governments Monti-Letta-Renzi, is that the choices in terms of the political economy were all consistent and aligned with the agenda set at the European level. In 2012, the fiscal compact was approved by the Italian Parliament with a vast majority and both pension and labour reforms have been introduced in line with the European requests.

The example of the Greek referendum on the bailout and the impossibility for Tsipras to avoid many of the fiscal cuts imposed by Europe, shows how strict the European rules are and how difficult it is to imagine a reversal in the economic policy at national level without a strong consensus of different European actors on issues regarding fiscal policies. Even the 5 Stars Movement, which intends to rule the country, will lose its credibility as political actor if it does not take these constraints into account.