Each summer, a 20,000-square-kilometer dead zone forms in the Gulf of Mexico. The cause of the lifeless water lies not in the gulf itself but on dry land, 2,000 kilometers upriver.

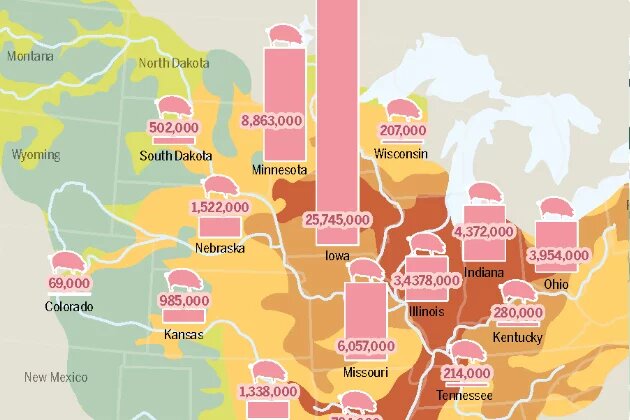

There, southwest of the Great Lakes, lies the Corn Belt, where most of the USA’s soy and corn are grown. Incredible amounts of artificial fertilizer and pig manure are used to fertilize these commercial crops. The region is also the heart of US pork production, with vast industrialized pig farms. All this industrialized agriculture produces massive amounts of waste products, including nitrates and phosphates. They contaminate the groundwater and then flow into the world’s fourth-longest river system, the Mississippi-Missouri, which ends in the Gulf of Mexico south of New Orleans. There they overfertilize the sea, causing the formation of huge oxygen-starved areas devoid of life.

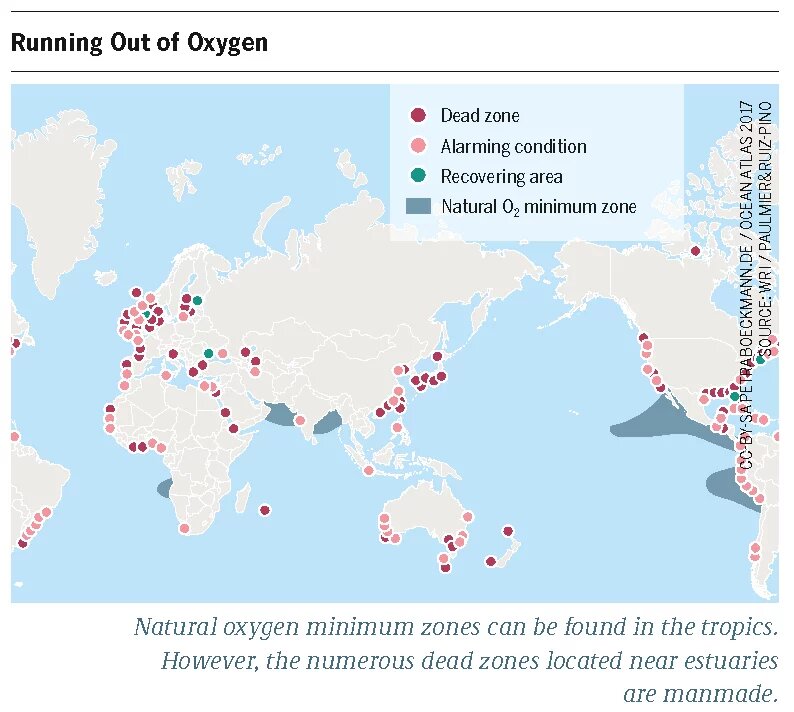

There are several such oxygen-deprived zones in the world’s oceans. Some of the largest occur naturally. They lie in tropical regions, like those o the coasts of Peru, Namibia, and the Arabian Peninsula. Only a few specially adapted organisms like bacteria live there. The dead zones near river deltas, however, are usually manmade – and they are growing. These areas should be home to fish, mussels, and shellfish, as well as meadows of sea grass and forests of seaweed. But those organisms need oxygen to live – oxygen that is in critically short supply there now.

Long before it was possible to identify the cause, fishermen had begun to call such areas dead zones. While they couldn’t have known about the lack of oxygen, it was readily apparent that something was amiss when they pulled in empty nets in waters that should have teemed Nebraska with life. The animals that could flee the dead zones, like fish and shellfish, had done so. And those that couldn’t, 69,000 like mussels and oysters, had died – 150 years ago.

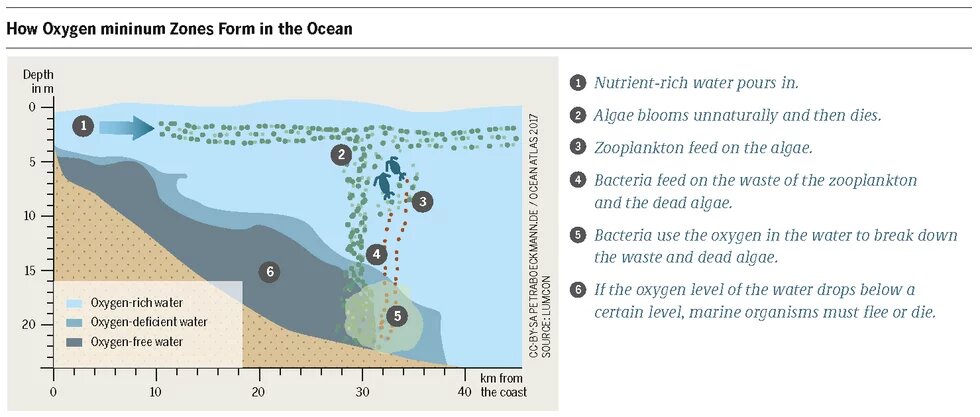

One cause was the growth of cities. As they grew, ever more wastewater flowed into the rivers and bays. Today there are filtration plants to deal with the wastewater, but ever since the middle of the last century, an even larger factor has emerged: we use so much artificial fertilizer in commercial agriculture that crops cannot absorb it all and it winds up in the ocean. Once there, it does its job all too well, stimulating the growth of plankton and algae. When these plants die, they sink to the seafloor where bacteria consume them – and in the process, use up the last bit of oxygen. For many species there is no escape.

The effects of the overfertilization of seawater – called eutrophication – can be observed in many places around the world, like the Pearl River Delta in the South China Sea or in India, where the Ganges flows into the Bay of Bengal. One of the largest dead zones is located in the Baltic Sea. It has experienced a striking reduction in oxygen concentration since the 1950s and 1960s. As in the deltas, the change is a consequence of industrialized agriculture. The effect is exacerbated there by the fact that the Baltic Sea is a flat inland sea with little water exchange.

From 1900 to the 1980s nitrate levels increased four times while phosphate levels increased eight times. The increase in fertilizers detected in the Baltic Sea was particularly large in the 1960s and 1980s. Values have steadfastly remained at this high level in the years since. In 2009 the Helsinki Commission (HELCOM) conducted the first comprehensive study of the Baltic Sea, examining 189 areas. The shocking result: only 11 were in good ecological condition.

All the same: something is being done. The Baltic Sea Action Plan, which has been ratified by all the countries bordering the sea, sets concrete goals for further reducing the flow of fertilizer. Phosphorus emissions are to be reduced by 15,250 tons per year while nitrogen emissions are to be reduced by 135,000 tons per year. The goal is a Baltic Sea free of eutrophication.

The plan is more than a non-binding statement of intent. For example, Germany had to appear before the European Court in September 2016 for violating the agreement. The country exceeded the limit for nitrates in groundwater by about one third, the result of too much pig manure in the groundwater. The German government faces six-figure fines – per day – as long as emissions continue to exceed the limit.

Eutrophication is a problem that cannot be solved without such agreements at the international level – national regulations are only effective if neighboring countries abide by the same rules. The coastal waters are part of the shared responsibility of the neighboring states. Teeming with fish, mussels, and shrimp, the seas are at their most productive there. At the same time, that is also where they face the greatest stress. The bitter irony is that the agricultural production of food is itself endangering a resource that we urgently need for the world’s food supply.

» You can download the entire Ocean Atlas here.