The Agenda 2030 is at its half-way point, yet the 17 goals for sustainable development remain a distant proposition. In the following conversation, Imme Scholz discusses the causes and points out how the global community may speed up their realisation.

What is the Agenda 2030? What are the 17 goals for sustainable development?

Imme Scholz: All 193 member states of the United Nations did agree on the Agenda 2030 in order to make the world a place in which everybody can live a better life – that is, a world without poverty and a world in which everyone has access to healthcare and education. All of this will have to be achieved without further damaging the natural foundations of life, which is important as, until now, increased wealth has gone hand in hand with the destruction of the environment and the climate crisis. This is what the Agenda 2030 is meant to address.

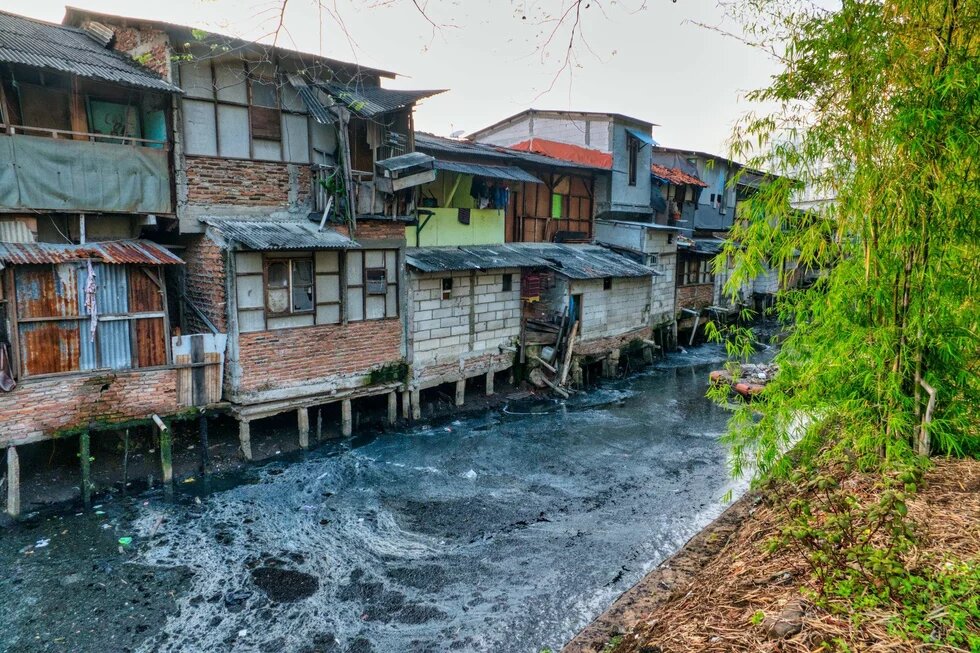

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs – see list below), which constitute the Agenda 2030, outline the envisioned goals the global community has pledged to make a reality. There are social development goals that aim to reduce poverty and inequality and that will tackle discrimination and strive towards gender equity. Then there are economic goals, for example, the general access to sustainable energy and humane working conditions for everyone. Finally, there are the environmental goals such as the fight against climate change and the loss of biodiversity. This also includes the cities, as they will have to change and become more liveable spaces.

Unfortunately, a democracy goal could not be agreed upon, as the non-democratic countries within the UN wouldn’t sign such a pledge. Still, there was agreement that all governments should work towards peace and effectively try to achieve the non-discrimination of their citizens in every respect. International co-operation is another important point, as all countries should be enabled to achieve the 17 Sustainable Development Goals – and that means they need to receive the resources necessary.

You just described some of the 17 goals. What is the central objective, what is the overarching principle that informs the Agenda 2030?

I would define this as achieving a good life for all – while, at the same time, preserving the natural foundations of life, meaning climate, soils and forests, lakes, rivers and oceans and biodiversity. This means all countries will have to change – and in that respect the Agenda 2030 differs from its predecessor, the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), as the latter solely applied to developing countries and in which the developed world, more or less, pledged to support their development through international co-operation. The MDGs as such, however, have not been put into question.

Regarding the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, the developing world has made it clear that the industrialised countries will have to do their share and make changes because, they should no longer be an obstacle that blocks the development of poorer countries. When it comes to protecting the natural foundations of life the onus is on the wealthier countries – and today that does not only mean the old industrialised countries but also large emerging nations such as China and India that have seen rapid economic development.

Do those requirements mean that it will be much harder to accomplish the goals in question?

For starters this seems to be a realistic assumption. You cannot stop climate change, if you view it solely as a task of the industrialised world. The G20 countries, that is the leading industrialised and emerging economies, are causing 80% of greenhouse gas emissions. China, the USA, India, the European Union and Russia are responsible for about 65% of these emissions. On the other hand, the per-capita emissions vary hugely between countries – which is a reflection of the vast differences in standards of living and infrastructure. Add to this goal no.10 – the reduction of inequalities – and you have a task at a national level that has to be tackled by all countries, as it involves not only gender equality but also equal rights for religious and ethnic minorities. At the same time, there are inequalities because international law is not implemented to the same degree in all parts of the world, while, on the other hand, the mechanisms of world trade will result in inequalities, even if they are are meant to be neutral. Here, rich and poor countries alike still have a lot to do.

Right now we’re at the half-way point. How much headway have we made on our journey towards realising the 17 Sustainable Development Goals?

It doesn’t look good. We’ve only made good progress for 12% of the 140 indicators; for 30% of them the outcome has been negative, meaning there’s been backsliding; and the remainder is somewhere in between, which means it will not be possible to reach these goals by 2030. On balance, this is a very poor performance – begging the question, why is it that we are performing so badly? The crises of the last few years have certainly been a setback, and this is especially true for the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic has lead to an increase in the numbers of those living in extreme poverty – and that to an even greater degree than during the 2008-2009 financial crisis. To mitigate the social effects of the pandemic and of isolation, many developing countries had to borrow money at very high interest, and this is a burden on their economies and their budgets. A second factor is the rise in food and energy prices that was caused by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. All of this means that it will be impossible to end extreme poverty by 2030.

However, as early as 2019 the Global Sustainable Development Report (GSDR) had concluded that, at the time, progress was too slow to reach all the goals by 2030. As a consequence, we, in our own report, pose the question whether this may have to do with the intrinsic difficulties of transformation processes. Many findings point that way. When reviewing the indicators with regard to Germany, we find that we’re in danger of missing the targets for the reduction of greenhouse gases, the expansion of renewable energy, the reduction of energy and resource usage and for wildlife conservation by 20% and more. The same is true for the reduction of diseases of affluence and premature mortality. For young people with no higher education or job training the indicators are even worse, their numbers are on the rise generally, and for young men they are worse still. Nor have we managed to reduce the number of foreign-born pupils that leave school without an advanced degree. As there is already a shortage of skilled personnel, the outlook is bleak.

The tasks at hand are complex: Regarding education we will have to improve our schools in order to enable them to provide equally for all children. Premature mortality is closely connected to nutrition and exercise. Here, it is important to change the taxation of sugars and fats and to pursue novel approaches in transport policy. The infrastructures for energy, traffic and production need to be reconfigured and manufacturing processes need to be overhauled so that they no longer endanger climate and biodiversity. For example, in agriculture, the EU has set the goal to reduce the use of pesticides by 50% – and this, as well as the other things I mentioned, we will have to adopt. Transformation means that very substantial change has to be achieved within a relatively short time period – and this will require a major effort from our societies. Still, it can be done.

We do possess the knowledge and the means to achieve this, and many people are willing to embrace such changes. However, rebuilding our economy will also trigger insecurity and fear and there will be resistance. Whether individual countries are ready to take on this challenge will greatly depend on their political landscape and on how much their societies will support it. The necessary changes are ambitious, yet they are essential if we want to achieve and preserve a good life. One consequence is that, in future, wealth will not be the same as what we perceive as wealth today.

To make this more tangible – you said that progress has been made on 12% of indicators, while we’ve been backsliding on others. Could you provide some examples?

Between 2020 and 2023 global progress has been made regarding the funds spent on research and development, the access to mobile phones and the internet, as well as on living conditions. The United Nations are confident that progress will also be made in the areas of social security, water treatment, access to electricity and energy efficiency. The reverse is true – and this has much to do with the COVID-19 pandemic – in areas such as extreme poverty, child mortality, vaccination rates, schooling, economic growth and the global rate of homicides. Especially worrying are subsidies for fossil fuels, as these have not gone down, quite the contrary, they have doubled. CO2 emissions are also on the rise, globally, and then there’s been backsliding on the protection of the fish in our oceans and in wildlife protection, generally. Also, the reduction of inequalities is making very slow progress indeed.

How binding are the sustainability goals that have been agreed upon?

In terms of international law the Agenda 2030 is non-binding. What makes it viable is that, again and again, governments have backed its tenets. There’s two reasons why I think we should stick to the Agenda: One, in many areas it lists all the right challenges that we are faced with; and, two, many countries around the globe still want to work towards realising its goals. In view of the crises we’re living through, it is especially important to have a platform for international co-operation – and that despite all other differences. For example, you can ask how far Saudi Arabia has come in making the goals a reality – and the same you can ask Germany. We also need to consider whether we’re doing enough to meet our national goals, as well as our goals regarding international co-operation and the global good. Herein lies the true political value of the Agenda and its goals.

This is also why, every July, we’re holding an annual meeting in New York where, for 14 days, countries will report on a voluntary basis about the progress they have made towards implementing the Agenda 2030 on a national level. This year, the focus will be on urban development, on inequalities, and on drinking water and waste water treatment. Such meetings offer countries the chance to learn from one another and to find out how others have managed to make progress. However, the way this transpires has its faults, as many countries are trying to shine, and thus they will report success stories only and leave out the failures. In order to make real progress it is thus crucial that such reporting doesn’t take place only in New York but in all countries too. When preparing a country report we need public consultations with input from many civil society actors, economic players and scientists. All of these should be able to comment on a government report in order to improve it or, alternatively, to present their own report. After all, the purpose of reporting is, among other things, to keep the citizens informed and to be accountable. In this way, civil society groups can use a public debate to put pressure on their government and nudge it towards implementing the sustainability goals. Ideally, such reporting would also take place in the German Parliament and Senate, thus lending the sustainability goals greater authority across different political sectors and improving co-operation between federal government and states.

What is Germany’s role in this process?

Germany was very actively involved in the discussions that lead up to the drafting of the Agenda 2030 – and it is one of the countries that, in 2016, presented their first national implementation plan. Responsible for implementing the Agenda 2030 is the German Chancellery, as it is in charge of Germany’s sustainability strategy. In theory this is a good starting point.

So Germany’s sustainability strategy is synonymous with Germany implementing the goals of the Agenda 2030 on the national level?

Exactly. This also comes with some challenges, however, as it leads to the creation of parallel processes. Strictly speaking, the Agenda 2030 should be a central tenet for each and every ministry – yet this is not the case. Every ministry has a person in charge of this issue; in the end, though, it is up to the respective minister to decide how much emphasis will be put on these goals. As a consequence, each time there’s a new government and a new minister the new person in charge has to be convinced of the importance of the issue. The sustainability strategy is meant to stress the crucial importance of sustainability beyond terms of office – and also to highlight all the things that do not go well. It is therefore essential that the goals are truly ambitious.

What is the role of the EU?

That depends on what policy area you’re looking at. The European Green Deal covers many of the sustainability goals. The plan is to make Europe carbon-neutral by 2050 and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 to at least 55% compared to the 1990 levels. It also proposes investment into a consequent remodelling of infrastructures and into the the creation of a circular economy that will be less wasteful, increase the life cycles of things and thus will let us reduce the import and consumption of resources. Agriculture and food production are meant to become more environmentally-friendly and the number of nature preserves is to rise.

The European Green Deal relies on the fact that it is able to motivate countries to participate by creating offsets between countries that have more resources – and thus greater responsibility – and those in a weaker position. The Next Generation Fund, for example, is a first and important step in this direction, as it enables EU member countries to finance measures mitigating the effects of the pandemic, yet these measures have to be designed in such a way that they do not contribute to climate change.

Such mechanisms, however, are needed across all policy areas. Also, the EU will have to support the sustainability goals internationally, for example, via its trade, investment and development policies. The EU’s research funding is another important aspect, as it helps to develop new technologies and transformation processes that are compatible with the actual situations different countries are faced with. Currently, 70% of people live in countries with little or no research and development capabilities. Consequently, the EU’s research policy needs to help develop such capabilities in poorer countries, as this is in the best interest of us all – and for this the COVID-19 pandemic has offered a good example.

It will be important that the parliamentary groups in favour of Europe taking a leading role in climate policy will be strengthened in the next Elections to the European Parliament, as they support constructive international policies and international co-operation.

What are the recommendations of the report you co-authored and that is meant to speed up progress towards achieving these goals?

What we recommend is that, in September 2023, countries will define a common framework on how to make global progress towards sustainable development. This includes, first and foremost, elaborating national action plans for all those areas where countries have seen stagnation of backsliding. Such plans should be ready by July 2024.

This sounds somewhat like the immediate action programmes laid out in Germany’s Climate Protection Law.

Right – and accordingly one has to ask: Why is it and what are the specific issues that hinder progress – and only then, once this has been answered, should we pass new measures and decide on action plans for 2024. For the wealthier countries this means that instead of just focussing on their national tasks, they will have to act internationally and help other countries along. Right now, many developing countries are facing a budgetary crisis, and 61 countries are on the verge of bankruptcy because the pandemic forced them to borrow – or because their revenue has dropped dramatically because of recession.

Such countries lack the resources to accomplish the badly needed transformation. As a consequence, our second urgent recommendation is to cancel the debt of the countries with the lowest income levels and to restructure the debt of the other countries. This is something on which the industrialised countries as the lender will have to take the lead – and when I say “industrialised countries” I also mean China, as its banks will have to join this initiative too. Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR), a joint project of Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center, the Centre for Sustainable Finance at London’s SOAS University and the Heinrich Böll Foundation, has come to the conclusion that 61 countries from the global South will need to have their foreign debt of over 800 billion US-$ restructured because otherwise they will be unable to meet their climate and development goals.

A further necessity is to improve the tax base in order to be able to finance the transformation. This is in the interest of all countries. Without very substantial public assistance, for example through tax incentives, the scrapping and redirecting of subsidies and through investment into new infrastructure, a transformation will be impossible. A further proposal that has also been modelled and calculated is to double the public budgets for healthcare and education in low-wage countries. Currently, those budgets are so minimal that doubling them would not be a major expense, yet one with very tangible results.

The social sector, too, needs more investment. All of this also has economic benefits because the economy needs well-trained staff in order to get ahead. People who have to mind their children or care for sick relatives are unable to pursue a career. At times, people tend to overlook the fact that welfare systems and investment into education also serve an economic purpose. The third point we emphasise is that we need investment to strengthen the economic, legal, political and social position of women. Doing this also means that countries will fulfil their obligation towards gender equity for women and girls. In addition, comparative studies have shown that gender equity has a positive impact on many of the other goals.

Can you provide some examples?

Women who are educated and have a stronger legal position tend to be active in the labour market and will set up their own enterprises, thus investing into the next generation. Another example, confirmed by studies, is that peace accords that are negotiated with the participation of women tend to be much more lasting and will benefit society as a whole. Women often don’t negotiate from the point of view of combatants, who want to get the greatest gain for their camp, but will take the perspective of civilian populations that were the helpless victims of war and who suffered from hunger and the destruction of infrastructures. Such women often know exactly which areas need to be rebuilt and reformed in order to achieve a sustainable peace. This leads me to the fourth point we emphasise. We need international efforts to end wars and conflicts because every year of war will substantially set back the societies involved – be it in social, environmental or economic terms.

In what ways do the activities of the Heinrich Böll Foundation help to achieve the sustainable development goals?

The foundation does this by putting the focus of its work on issues such as human rights, democracy, gender equality and on questions to do with the social-environmental transformation. We are co-operating with over 100 partner organisations in around 60 countries and, together, we are tackling the global challenges as laid out in the Sustainable Development Goals. For us it is essential to be working with partners because it is they who know best how to approach certain issues in a specific context. Together with our partners we aim to initiate and promote change – and to make their perspectives, which often challenge the status quo, heard on the international stage. This is one way in which we are addressing global inequalities.

Within Germany, too, our political education programmes aim to strengthen democracy and promote transformation in the domestic arena. In this, our 16 state foundations – and the way they co-operate within our foundation network – plays an important role. Another important unit of the Heinrich Böll Foundation is the feminist Gunda Werner Institute that, in concert with its partners, promotes gender democracy, the rights of LGBTIQ and takes a stance against anti-feminist discourses. Finally, our scholarship holders and fellows have formed interdisciplinary work groups that address different aspects of transformation. It is our goal to use the whole multitude of our programmes to strengthen people and organisations and to work jointly towards a better and more sustainable future for all. In the 21st century, global justice will be impossible without an environmental redesign of society and economy – but it also requires political freedom, campaigning against discrimination and marginalisation and defending the human rights of all people. This is what I stand for – and this is why I decided to join the Foundation.

Translated from the German by Bernd Herrmann.

Since April 2022, Dr. Imme Scholz has been serving as co-president of the Heinrich Böll Foundation. Imme Scholz is also co-chair of the Independent Group of Scientists that has been commissioned by the United Nations to prepare, until September 2023, the Global Sustainable Development Report (GSDR), that is, the second scientific report regarding the implementation of the sustainability goals.