Grand visions, bold announcements – yet implementation remains sluggish. Green hydrogen was hailed early on as a beacon of hope for the Global South. But without fundamental policy shifts, the project risks falling into familiar patterns of raw material export and asymmetric dependency. What’s needed are genuine industrial partnerships that relocate value creation to regions where renewable energy is especially cheap.

“Green hydrogen could be the oil of the future,” declared Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro in 2024 during a meeting with Olaf Scholz in Bogotá. He cited “the Germans” to back up his statement (Mejia 2024). This marked a clear stance against fossil fuel dependency – and a jab at Brazil’s President Lula, who is pursuing new oil sources at the mouth of the Amazon. Petro envisions a different model: industrial use of renewable energy, including green hydrogen. Symbolically, he proposed a partnership between Colombia’s Ecopetrol and Brazil’s Petrobras – a pivot from oil to hydrogen as a driver of development and prosperity (El nuevo signo 2024, Hydrogen Council 2017).

But can green hydrogen deliver on its promise – as a climate-friendly energy source, geopolitical tool, and engine of economic growth? Many Global South countries hope for new export opportunities (Cabaña 2024). Germany is actively promoting the rollout: with over 20 bilateral hydrogen partnerships, including with Namibia, South Africa, Brazil, and Morocco. Programs like H2Global, H2Uppp, and the H2-Diplo network aim to stimulate investment, promote technology exports, and enable fair supply chains – while also securing domestic supply (BMWK 2024).

How hydrogen became a beacon of hope

The idea of solving the climate crisis with hydrogen and forging new geopolitical alliances inspired politics, industry, and the public alike. Between 2020 and 2023, expectations skyrocketed: green hydrogen was to replace fossil fuels, decarbonize industry and transport, and create opportunities in the Global South. In 2020, BloombergNEF forecast that hydrogen could account for a quarter of global energy consumption by 2050 (BloombergNEF 2020). The IEA projected up to 700 million tons annually. At COP27 in Egypt in November 2022, Chancellor Scholz announced over 4 billion euros of investment in the hydrogen market. In the U.S., President Biden made “clean” hydrogen a pillar of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). China, too, invested heavily in electrolysis, aiming to dominate the market as it has with solar photovoltaics.

The number of announced projects grew rapidly (Hydrogen Council & McKinsey 2021). Companies like mining giant Fortescue announced gigawatt-scale projects, and many countries developed ambitious hydrogen strategies. Hydrogen became part of a "just transition" narrative: green industrialization and a new international division of labor. But criticism soon followed – regarding definitions, large-scale projects lacking local consent, and the inclusion of gas and nuclear infrastructure under the “clean” label.

Civil society actors intervene against new extractivism

Starting in 2021, civil society organizations began calling for binding guidelines for a responsible hydrogen economy (Tunn et al. 2024). Key questions emerged: Is hydrogen becoming a tool of a new extractivism? Will land and water be appropriated in the name of climate protection? (Barnard 2022, Corporate Europe Observatory 2023, Ammar & Ammar 2024)

Brot für die Welt and the Heinrich Böll Foundation published a synthesis report outlining ten minimum criteria – including environmental impact assessments, transparent land use, biodiversity protection, and Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) for Indigenous communities (Villagrasa 2022).

International actors also developed standards: the Hydrogen Council published ESG criteria; the H2Global Foundation released a sustainability concept; and the IPHE network created common principles in the “Joint Agreement on the Responsible Deployment of Renewables Based Hydrogen” (Hydrogen Council & McKinsey 2021, UN Climate Champions 2023). The goal: social and ecological compatibility, and the foundation for credible certification.

Germany’s hydrogen strategy (BMWK 2023) adopted many of these principles. However, efforts by civil society to make them binding in the 2024 import strategy failed due to resistance from the Chancellor’s Office (Klima-Allianz et al. 2024, Nationaler Wasserstoffrat 2021). While the development ministry (BMZ) supported sustainability obligations, the Chancellor’s Office blocked them – fearing competitive disadvantages and implementation hurdles. The result: many declarations of intent, but few binding rules.

The hydrogen revolution is facing delays

By 2024, it became clear: the global rollout of green hydrogen is slower and more selective than expected (Polly 2024, Tsvetana 2024). Investment decisions for major projects – such as in Namibia, South Africa, or Chile – are delayed or suspended (Ladera Sur 2023). Reasons include a lack of offtake agreements, high capital costs in the Global South, infrastructure uncertainty, and competition from direct electrification. Even Fortescue, once a pioneer, is increasingly turning to battery-electric solutions for its own mining operations (Liebherr 2024).

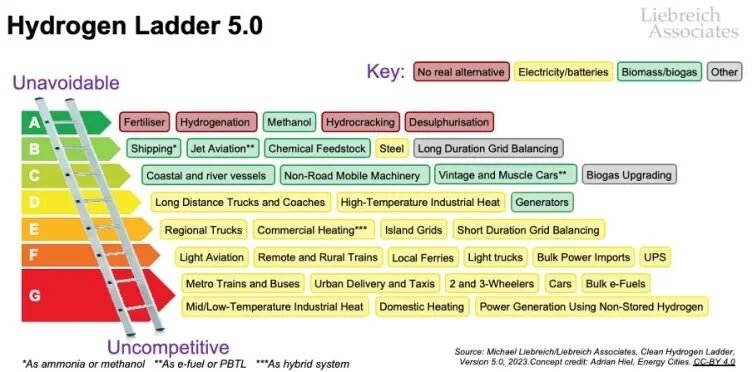

In Europe, plans are also being revised. According to BloombergNEF and Aurora Energy Research, anticipated demand falls far short of EU and member state targets (BloombergNEF 2024). Many applications – such as passenger cars, building heating, or electrifiable industrial processes – appear increasingly uneconomical. Michael Liebreich’s “Hydrogen Ladder” has shaped the debate on prioritization: steel, aviation, and shipping at the top; passenger cars, heating, and off-grid power at the bottom (Liebreich 2023, 2024).

Instead of a global hydrogen economy, 2025 is characterized by pilot projects, regional clusters, and state-backed initiatives – mainly in countries with sovereign wealth funds like Saudi Arabia, Oman, or the UAE, which have low capital costs. In poorer countries with unstable governance, investment remains scarce. This softens fears of green colonialism: investments depend not only on renewable potential, but also on political stability and favorable financing (Dejonghe & Van de Graaf 2025, Tunn et al. 2025).

Green industrialization must replace raw material exports

What remains for developing countries? The dream of prosperity through green hydrogen remains risky. Some Global South countries do have world-class solar and wind resources that allow them to produce green hydrogen at very low costs. However, regions with favorable wind and solar potential are so widespread globally that significant scarcity rents, like those seen with oil, are unlikely. For example, the Fraunhofer Institute confirms that Colombia under Gustavo Petro has major potential in three regions (Hank et al. 2024). Yet regions like La Guajira, with a strong presence of paramilitary groups, are so insecure that billion-dollar investments seem implausible.

So, green hydrogen will not become the new oil. But it may become a building block for green industrialization in the Global South. For this to happen, the Global North must also change its policies. As a major importer and consumer of green hydrogen, Germany could enter into reliable partnerships with producer countries based on strict environmental and social standards and significantly increased local value creation. This would greatly enhance development impacts – particularly in terms of job creation.

Several studies show that relocating parts of the value chain for energy-intensive products to regions with cheap renewable energy leads to significant cost advantages (Verpoort et al. 2024, Steitz & Kölschbach Ortego 2023, Bähr et al. 2023). This points to the potential for long-term, reliable partnerships with countries not merely as resource suppliers, but as industrial partners on equal footing – which would also serve Germany’s own interests. However, this would require partially phasing out some basic industries in Germany. Is that politically sustainable?

In such a partnership, Germany and other energy-importing countries must systematically support exporting nations in their efforts to secure value creation locally. Green industrial partnerships instead of hydrogen partnerships – that should be the direction. But is there the political will to do so? So far, there seems to be a stronger readiness to use massive state subsidies to preserve the old industrial structure into the post-fossil age. The question is: how long can that be sustained?