The Indian national identity system, Aadhaar, was set up to improve efficiency in welfare programs, empower disadvantaged groups, and enable digital innovation. However, it has sparked protests and fears of government intrusion. ➢ More in our special on Digital Asia.

The digital revolution has made information accessible to people on a massive scale. However, it has also made information about people equally easy to access. Thus, private companies and governments can collect vast amounts of data as people make electronic transactions, access services, or share their personal lives online. Against this background, societies have to decide where to draw the line between the benefits of digital data and the loss of privacy. In India, this struggle is being played out over the national identity system, known as Aadhaar.

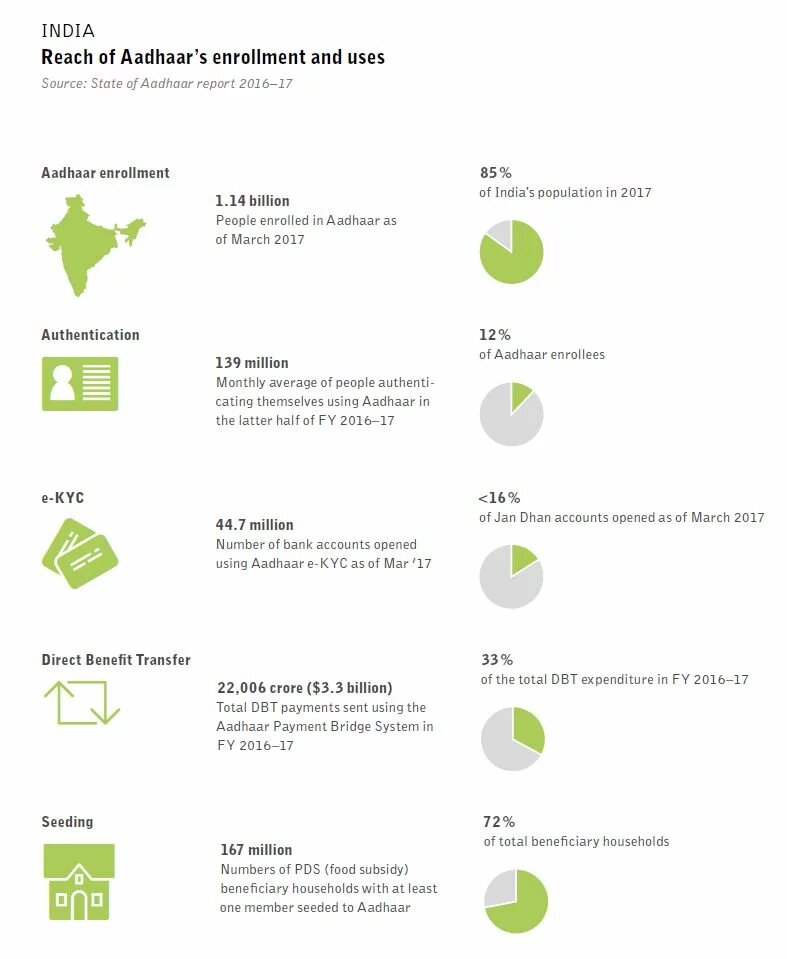

Aadhaar is a central government program that ensures each legal resident (foreign included) in the country has one unique identity based on biometric data that includes facial image, fingerprints, and iris scans. It also collects basic demographic data such as address, date of birth, and a parent’s name. The government initiated work on it in 2009, and the first ID number was issued in 2010. Today, Aadhaar is the world’s largest biometric ID system, with nearly 1.2 billion enrolled members.

At first, the Indian government promoted Aadhaar as a tool to improve efficiency in welfare programs. Now the ID is required for dozens of other government and private business services. In most cases, beneficiaries are only required to add their number to their accounts. For example, by adding it to a bank account, individuals can receive welfare payments through direct deposit. In other cases, such as for food distribution, they must perform a fingerprint or iris scan at the distribution point.

Two main concerns prompted the government to consider a unique identity for all citizens. The first was to prevent fraud through multiple identities. The other was to expand benefits coverage to those who had no identity documents, including a substantial portion of women. Thus, the idea of tying subsidies to an individual biometrics-based ID caught on. It would ensure that everyone had one – and only one – identity, and it guaranteed the precise targeting of benefits. The idea appealed to politicians and the private sector as a bold, modernizing step for India, and it became a core part of the strategy known as “Digital India.” Decision-makers saw in Aadhaar the potential to transform day-to-day transactions and go from using dog-eared ID cards and handwritten ledgers to paperless digital records.

Good intentions but a bumpy start

Despite the good intentions, the adoption of Aadhaar got off to a bumpy start. It was initially a bureaucratic creation not backed by any law. This led to numerous court challenges, and the ID did not come into use until February 2016, when the legislature passed the Aadhaar Act. However, lacking the adequate number of votes in the upper house, the ruling party used a shortened legislative process meant for taxation and spending bills. This led to further court challenges and an outcry that demanded consultations be held with the public.

While cases piled up at the Supreme Court, the central government continued to issue regulations that required the Aadhaar program for many other welfare entitlements (school lunches, crop insurance, vocational training, Bhopal gas leak compensation), financial activities (filing tax returns, opening bank accounts, large money transfers), and private business services (mobile phone connection, purchase of high-value items).

Aside from the legal challenges, Aadhaar also faces a legitimacy challenge. Although some saw in Aadhaar exciting new possibilities for digital initiatives, it was met with criticism from civil society at its very introduction. To better understand the arguments on both sides, it is necessary to examine the potential benefits and criticisms of Aadhaar.

Getting rid of paperwork and facilitating transactions

Aadhaar was initially offered as a remedy to perceived leakages in welfare programs, but it also offered a way to transform identity management in India. Since 2016, the central government has embraced both uses with vigor, requiring the ID for almost all interactions. By attaching their Aadhaar identity to online accounts, people may electronically sign online forms, eliminating the need for paper documents and signatures. State governments have also started requiring it, even for students to participate in sporting events. In nearly all cases, its use is justified as a way to prevent fraud, such as sending a stand-in for tests or examinations.

Beyond using Aadhaar as a control over identity, the central government has created several digital initiatives that promise to transform what is considered business as usual. The government empowered a semi-private organization to create a payment infrastructure to enable the easy transfer of money between individuals and businesses. Private businesses may also use Aadhaar to authenticate the identities of employees or clients. Many companies need to establish customers’ identities, sometimes by law, as in the case of mobile network operators. Aadhaar can speed up this process by using fingerprint scanners to instantly establish a person’s identity in order to get a mobile connection. In 2016, for instance, the Reliance Company enrolled about 100 million customers in less than a year by sending service representatives with connected scanners to customers’ homes.

These examples show that Aadhaar does indeed hold great potential on multiple levels. Individuals need to provide less paperwork for registrations while government agencies can target beneficiaries of programs more easily. Businesses benefit too, because Aadhaar offers the possibility to streamline identification methods and thereby reduce fraud.

Digital dreams for some, dystopian nightmares for others

Of the many criticisms of Aadhaar, one of the main ones has been that Aadhaar fails to deliver the promised benefits. For example, opponents have challenged the cost savings in welfare programs attributed to it. They argue that fraud in welfare programs was already dropping starting in 2010 due to factors that had nothing to do with the new ID system. The lack of sufficient analysis makes it hard to know whether Aadhaar is generating savings, but so far, neither side has produced any solid data to support their views.

Another argument against Aadhaar is that the ID system fails to authenticate a person if their fingerprints are worn off, or if they have had cataract surgery, thus increasing the number of people who are excluded from benefits. Estimates for this type of failure are typically around 5 percent, but some put it as high as 10 percent. Even the lower rate would mean – in a population of more than 1.3 billion – an unacceptably high number of excluded people. Failures in the system do need to be pointed out so that they may be fixed. However, it is unclear how failures are defined and how pervasive they are. A “failure” could refer to a single instance of verification, or to the overall outcome. For example, say a person tries to authenticate with a thumb scan and fails, but then they succeed with another finger. Depending on the definition, the failure rate is either 50 percent or zero.

Critics also worry about the possibility of the unauthorized copying of biometrics. If someone else gets a person’s fingerprints, they are forever compromised, since it is not possible to change fingerprints like passwords. Moreover, individuals cannot control how fingerprint authentications can be used. If a bank, for instance, implements a poorly conceived system that only needs a fingerprint to transfer money, someone whose fingerprints were copied may lose their money without ever lifting a finger, as it were. To counter this threat, the government needs to adopt guidelines and regulations to prevent the misuse of biometric data.

The most vocal argument against Aadhaar is the concern of civil rights organizations that biometric data could be used for state surveillance. It is true that Aadhaar could potentially allow for the introduction of a physical presence surveillance system, and the appeal of such a system to governments for security reasons should not be lightly dismissed. Yet, such a system is also highly improbable. It would require immense investment in sensors, network infrastructure, and data storage. Setting it up and funding it would not go unnoticed. However, in order to gain the confidence of skeptics and mitigate these fears, lawmakers should limit the government’s use of biometric data from Aadhaar for the purposes of surveillance.

Coupled with fears of biometric surveillance is the concern that Aadhaar enables the government to intrude into people’s private lives. Critics have raised the specter of the government monitoring people’s every purchase, thus knowing even small details such as what they eat and the color of their car. Although a unique individual ID that is common to all databases would make such tracking easier, it is also possible to do so without an individual ID. In the United States, which does not have an ID system like Aadhaar, the government planned a widespread data-collection initiative called Total Information Awareness (TIA) in the early 2000s. TIA was eventually defunded due to the public outcry over privacy concerns. The Indian government has already implemented its own version of TIA called Natgrid. Therefore, the true threat to privacy is not created by Aadhaar, but rather by government attempts at increasingly intrusive tracking.

Aadhaar is a system that is too big to fail

Despite the many criticisms of Aadhaar and the court challenges, there has not been a popular uprising against it. Since 88 percent of the estimated population has already applied for an Aadhaar number, it seems that most people have accepted it as a fact of life. Furthermore, the biometric ID system forms a cornerstone of the government’s vision of digital society, so it will not give up on Aadhaar easily.

Some groups, such as female heads of households, have actively welcomed it because it gives them more control over their finances. There is even evidence that Aadhaar is a tool that can empower women to become more independent. For example, Aadhaar has dramatically increased female participation in formal banking activities.

Opponents of Aadhaar want to dismantle the system and destroy the database. However, Aadhaar has come to be the primary identity document for many people. Those who are economically better off may have a driver’s license, a tax ID card, or a passport, but the poorest members of society may only have Aadhaar. If they no longer have their ration cards, their right-to-work cards, or other such documents, shutting down Aadhaar would be a blow to them. Since Aadhaar has become widely entrenched in many systems, a rollback now might cause havoc.

Going forward, data privacy concerns do need to be addressed. There are many adversarial actors – from private espionage groups to foreign governments – who may try to exploit data vulnerabilities. There is also the threat of abuse of power by future governments. Creating and instilling strong privacy protection laws now may decrease these risks. Here, the European Union’s General Data Protect Regulations would be a good model to follow. In order to uphold democratic values, the government also needs to curtail its own powers concerning the tracking of all citizens and prevent the needless collection of data. Such protections may assuage the fears of critics and uphold Aadhaar’s long-term legitimacy. The good news is that policymakers do seem to have taken notice of the need for a privacy law, and news reports say that they are working on a draft bill. If the legislative process takes into account public feedback and addresses the privacy concerns that people have with Aadhaar, it would provide a solid basis for more digital initiatives.

This article is part of our special on Digital Asia.