To the outside world, the mysterious Middle Kingdom presents many paradoxical characteristics in its development of information and communication technologies: China suffers from draconian internet regulations, but it also enjoys a prosperous internet marketplace; it attracts IT giants from the United States and Europe, but it has also expelled some of them.

This article is part of our special on Digital Asia.

How do international internet companies survive in China? What defines the relationship between Silicon Valley giants and Beijing? This article discusses the dynamics and relations of internet giants with China. It contends that the internet ecology in China should be viewed as a complex web of interactions involving the Chinese authorities, international internet giants, as well as domestic IT firms.

A giant’s dilemma: A tale of two worlds

China’s persistent efforts to build an internet empire have been apparent for the last three decades. For Western tech companies, however, entering the Chinese market has not been smooth sailing, given the stringent government rules, censorship, and surveillance. A prime example is the Google-China conflict of March 2010, when Google announced its departure from China’s search-engine market due to various difficulties, including “highly sophisticated and targeted attacks” it had suffered within the country.

The conflict is obvious. Whereas some emphasize the internet’s innately liberating qualities, Beijing views the technology mainly as a utilitarian tool to drive China’s wealth and power. Beijing has always regarded the internet to be an effective means of “economic and social development,” as it has stated repeatedly.

Beijing has also been a strong advocate of “internet sovereignty,” meaning that the national government has the right to regulate the internet as it sees fit, so long as the computer network involves equipment, personnel, and resources that fall within China’s jurisdiction. Such a stance on sovereignty contrasts sharply with the internet freedom discourse that has been encouraged by Western countries.

Google’s withdrawal from China boosts its credentials on ethics, but it also means giving up an enormous market. Other big tech companies from the West have had difficulties, too, as Chinese authorities have blocked Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Dropbox, and 3,000 other websites and online platforms.

Marching into the Chinese market as a mixed blessing

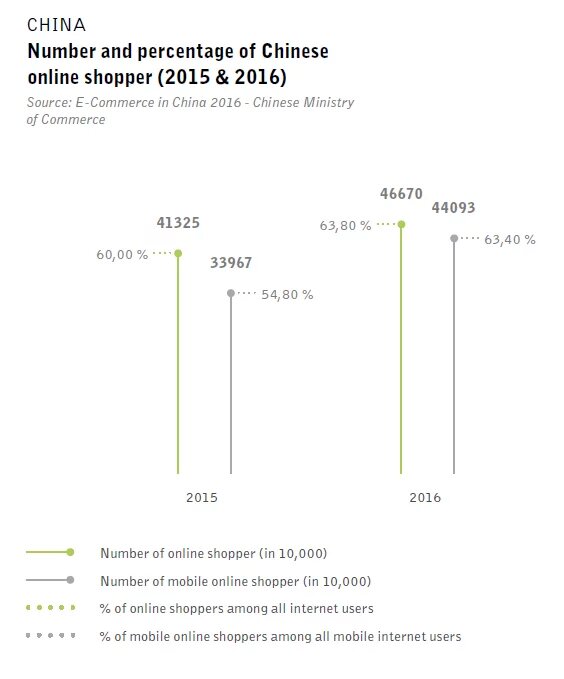

For large platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, marching into the Chinese market would be a mixed blessing. Their entry would provide them access to 710 million Chinese internet users and a significant increase in their global businesses.

However, the involvement would also necessitate compliance with Beijing’s regulations, censorship, and even possibly force them to sacrifice user privacy and information security. For example, to meet their regulatory obligations, Facebook and Twitter would have to require its users to register with real names and conduct self-censorship. Is this a trade-off that they are willing to accept?

Giant tech companies, in this sense, are stuck in the middle: between the enormous size of the market on the one hand, and the principles of internet freedom on the other. Although many Chinese people are trying to go beyond the “Great Firewall” to access blocked foreign webpages – an activity known as “scaling the wall” (fanqiang) – this has become considerably harder since 2013, when President Xi further tightened the government’s control over the internet.

Therefore, it is unsurprising to find companies such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter being marginalized in China’s cyberspace, as well as the emergence of an almost entirely parallel Web 2.0 and social media world that is distinct from the norms of the global internet.

BAT: Replicas of Western giants

What kinds of social media platforms do Chinese people use? Who develops them? How do these digital platforms survive in China? If you travel around, it is common to find people using WeChat or Sina Weibo. These are social media platforms similar to WhatsApp, Facebook, and Twitter. It is interesting that most of the global digital platforms can find their replicas in China, albeit with slight differences.

With regard to homegrown digital media entities, BAT companies are leading the way. BAT is an acronym combining the initials of three jockeying IT giants in China: Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent. Despite some overlap, the three giants’ core businesses are distinct. Baidu is China’s leading search engine, which is also involved in most online businesses such as blogs, forums, and online encyclopedias.

Alibaba, famous for its $25 billion recording-breaking IPO on the New York Stock Exchange in 2014, is China’s e-commerce giant. Tencent is currently the most valued internet company in online games and instant messaging and owns the two most prevalent social media platforms in China: QQ and WeChat. Like Apple, Google, Facebook, and Amazon, which frequently trespass on each other’s turf, the BAT companies also survive and thrive by competing and cooperating with each other.

From a Chinese perspective, domestic IT companies hold an obvious advantage due to their captive market because Facebook and Twitter have been blocked in China and Google has made its exit. However, although they have benefited from the absence of Western IT giants, this is not the only reason for their success.

The willingness to comply with state regulations

One has to also acknowledge that the trio holds the largest pool of creative talents in the country. By 2016, the total number of employees at Tencent had exceeded 25,000. Due to the state policy of encouraging entrepreneurship and innovation, BAT has become the tech powerhouse of China by maintaining thousands of incubators and research centers. More importantly, as domestic companies, they are very familiar with the Chinese market and have established ways to stabilize and increase market demand.

The business success of a tech company in China depends a lot on the management’s willingness to comply with state regulations. For instance, WeChat and Sina Weibo are actively involved in content censorship in China, and this kind of situation has deteriorated since 2017, in that more regulations on microblogging, VPN, and WeChat groups have been issued by the Beijing government.

The censorship system is efficient in targeting sensitive issues in social media discussions and redirecting them to “Not Found” pages. Meanwhile, domestic tech giants have built good relations with different hierarchies of local and regional governments – an advantage that foreign competitors such as Facebook and Twitter would not have enjoyed had they been admitted to the Chinese market.

This is because, on the one hand, on different levels of the Chinese government, there is skepticism of foreign IT companies, as they are seen as dangerous institutions promoting Western ideologies. On the other hand, many Western IT giants confront difficulties in balancing the freedom of speech of their customers with the stringent censoring requirements of the government.

Playing a hard game

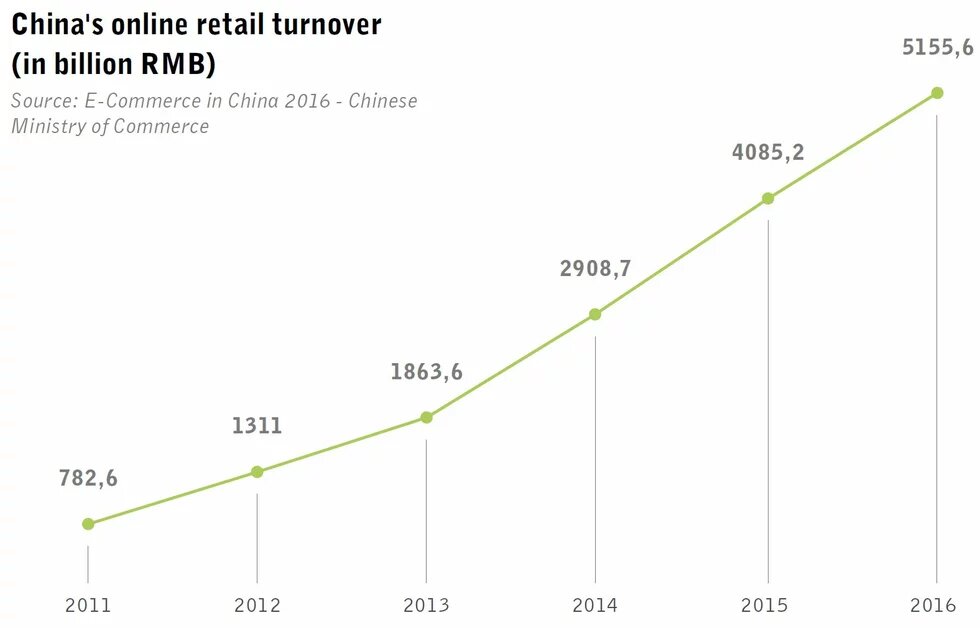

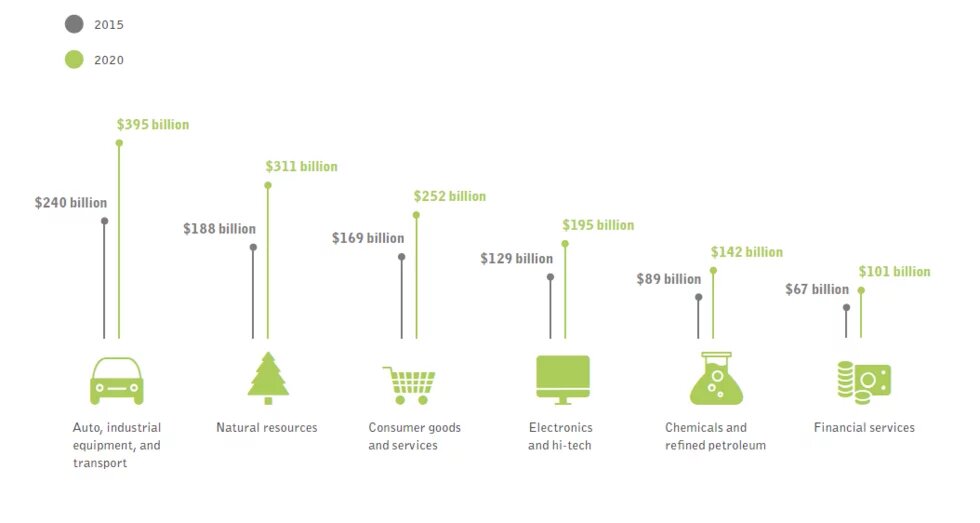

The rapid expansion of China’s consumer base has made the country immensely important for a broad spectrum of technology products. Some big corporations such as Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft have chosen to enter the market and have started to gain a footing in China, despite its reputation as one of the world’s most restricted internet markets.

Last year, Apple’s overall revenue in greater China jumped to $59 billion. However, like many other international companies, Apple’s success in China came at a cost. In order to maintain its business, Apple had to concede to Chinese authorities on issues concerning self-censorship and cooperation in terms of data storage.

In 2015, Apple disabled one of its new apps in China to prevent Chinese people from accessing sensitive issues banned by Beijing. Moreover, earlier this year, Apple announced that it will be opening a new data center in mainland China, in cooperation with the state-owned China Telecom company, to comply with a new law requiring data on Chinese citizens to be kept within China. It is not hard to see that the Chinese government remains a decisive factor in Apple’s overall business in China.

Other foreign platforms are also actively encouraging self-censorship. In 2015, Line, a Japanese messaging app, employed a keyword filtering system to ensure that politically sensitive issues are not discussed in the Chinese version of its product. Similarly, LinkedIn relies on in-house censors and algorithms to screen out “harmful” content from its Chinese website. These companies must promote self-censorship with their products if they do not want to enrage Beijing and get banned.

Increased control

Over the years, the control exercised by Chinese leadership over the internet has increased notably. After Xi Jinping became president, he appointed himself the leader of the Central Leading Group for Internet Security and Informatization, so as to better take control of the computer networks – from basic infrastructure to tech companies.

Meanwhile, the government has attempted to tighten its grip on internet content. In 2013, a Chinese court announced that the criminal charge of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” could be extended to cover online speech. A more recent regulation has formally approved the power of authorities to access citizens’ online information, if deemed necessary for legal investigations.

Besides political intervention, large global internet players also have to confront fierce competition from local companies. eBay first entered China in 2002, but it shut down operations in 2006 due to intense competition from Taobao.com. The survival of Amazon in China is in this sense surprising, although it still competes with many Chinese competitors such as Taobao, Tmall, JD, Suning, and other rising companies.

Apple faces similar competition. By July 2017, Apple only ranked fifth in China’s smartphone market, behind Huawei, Oppo, Vivo, and Xiaomi – the four Chinese smartphone brands that collectively account for almost 70 percent of the domestic market share.

Ways of access

Foreign companies, however, have never ceased exploring potential opportunities in the gargantuan Chinese market, despite the popularity of their replicas and stringent government regulations. In order to gain admission and have a piece of the market, foreign internet companies look for Chinese partners through joint ventures. By finding domestic partners, many international digital platforms have successfully entered and branched out in China.

For example, NHN, one of the world’s biggest internet content service operators, marched into China by joining hands with Qihoo 360. In 2005, Yahoo! chose to ally with Alibaba and expand its Chinese operations. At the beginning of 2016, Qualcomm also formed a joint venture with Guizhou Huaxintong Semiconductor Technology to invest in chip server technology, a sector that the local government was keen to develop.

Fitting themselves into joint ventures helps these companies become more localized and adaptable. However, this does not eliminate all obstacles. Besides online surveillance, Chinese authorities are also sensitive to issues such as technology transfer, corporate governance, the protection of local brands, as well as information security. The preference is, of course, that foreign tech companies provide China with their core technology and advanced management models.

In 2015, Microsoft announced its partnership with the China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC), a state-owned company, to “license, deploy, manage and optimize Windows 10 for China’s government agencies and certain state-owned enterprises and provide ongoing support and services for these customers.”

Difficult for social media platforms

Microsoft management is happy to rub shoulders with Beijing officials. According to Microsoft Corporate Vice President Yusuf Mehdi, “This venture signals the possibility for new opportunities for Windows 10 in the many government entities in China.” However, just in 2014, Microsoft 8 was banned by the Chinese government due to a concern over information security.

The cooperation between Microsoft and CETC again is indicative of the unpredictable relations between the Beijing central government and foreign internet capital. In order to survive in China, foreign tech companies are learning to remain on good terms with the government.

For social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, entering China seems much more difficult. First, if they were to enter China, the massive global scale of these two platforms would necessitate a very complicated censorship system. Compared with WeChat and Sina Weibo, in which Chinese is the main language employed, Facebook offers more than 140 languages, and Twitter is available in 33 languages.

Both allow users to make friends, join groups, and create public debates that can reach people all over the world. It is easy to imagine that the Chinese government would be the last to want to see “Tibet independence” or “Falun Gong crackdown” on these social media platforms in different languages.

Second, launching Facebook or Twitter in China would be nothing short of miracle, not only due to China’s draconian internet regulations, but also its even tighter control of internet speech under President Xi. Although Mark Zuckerberg is actively seeking chances to communicate with Beijing, he must also come to terms with the fact that he will need to make concessions in order to operate in China, otherwise Facebook would risk becoming the next Don Quixote, fighting for something unrealistic.

Accessing markets is not just a problem faced by digital platforms such as Facebook and Google, but it is also an imperative issue for Beijing and the Chinese people.

As one post in Zhihu (a Chinese Q&A website similar to Quora) says, today’s Chinese IT ecology is “not only about how Facebook gets into China, but also how Chinese people cross the Great Wall and reach every corner of the world” – the end of the sentence referring precisely to the first email ever sent from China, in 1987, which read, “Across the Great Wall, we can reach every corner in the world.”

The original version of this article was published on December 31, 2016, by La Vanguardia. It is part of our special on Digital Asia.