Climate governance has been captured by solutions that involve the financialization of nature. The first COP in the Amazon is an opportunity to face head-on the impacts and contradictions of these projects, betting on the rights and territorial sovereignty of Amazonian populations.

The prospect of COP30 being held in Brazil, in the capital of the State of Pará, Belém, in 2025, has put the Amazon back at the center of the debate on international climate and environmental governance. In fact, the issue of defending forests – and the Amazon in particular – has always played a key role and is intertwined with the scientific and political trajectory that led to the consolidation of a regime to “govern the climate” – an achievement of such magnitude and scope that it is unparalleled in history.

At the time of the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, when the conventions on climate change (UNFCCC) and biodiversity (CBD) were signed, followed by the United Nations Convention on Combating Desertification (UNCCD), there was a major campaign for a specific legal instrument on forests – which was vehemently rejected by Brazil, arguing that efforts are needed to focus on the energy and technological transition and on overcoming the global fossil fuel matrix, in addition to addressing issues related to the sovereignty of countries that own rainforests. In Brazil, historically, the issue of national sovereignty over the Amazon has been a key theme in the national identity, a mobilizing force in the political imagination, as well as a strategic territory for the country’s development project – for better or for worse. Three decades later, the context could not be more different.

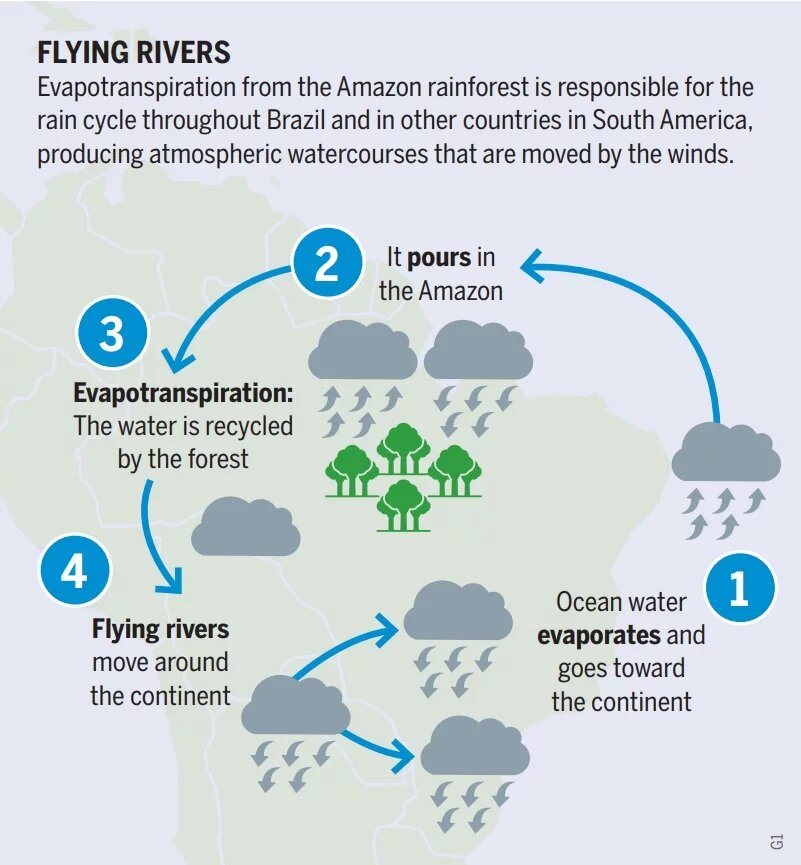

The Amazon has established itself as perhaps the most valuable environmental asset in the new climate economy – virtually a symbol of the global environmental cause. In practice, the Amazon currently represents the largest continuous stretch of rainforest in the world. It is also a source of strategic resources, particularly freshwater and biodiversity. Furthermore, its lands are geostrategically positioned to meet the new demands of global commodity trade, which has driven the development of new logistical routes – such as waterways, railways, and ports – to support the expansion of agribusiness, hydroelectric power plants, and mining industries.

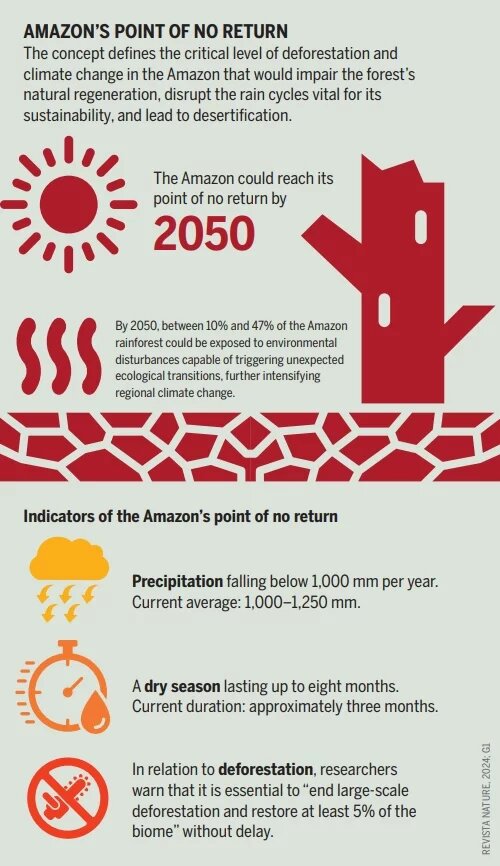

Under intense pressure from the current development model and from both old and emerging global value chains, the forest may have already embarked on the path toward its “point of no return,” as warned by a study published in the journal Nature in February 2024.

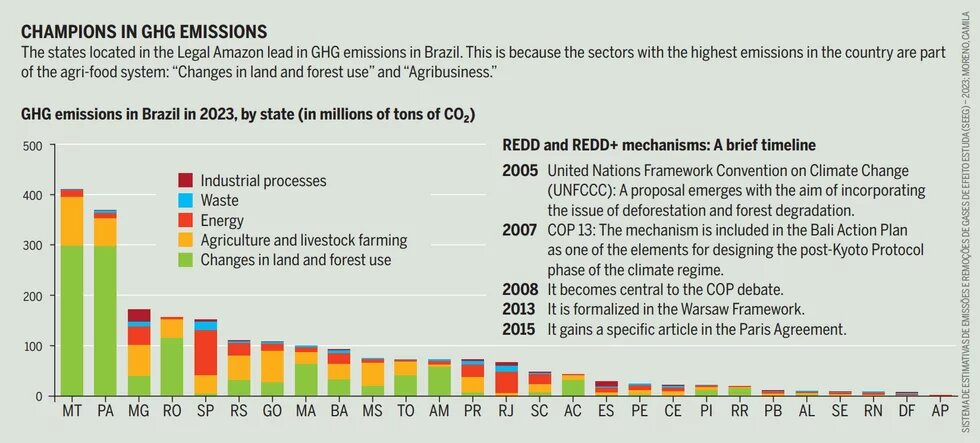

The future of forests currently occupies a very prominent place on the climate agenda. In recent years, the centrality of the role of forests in the planet’s global temperature regulation system has come back into the spotlight with force, with the incorporation of the REDD+ mechanism under the umbrella of nature-based solutions [REDD+: Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, the plus stands for further measures such conservation, sustainable forest management, and the enhancement of forest carbon stocks]. These include the biological capture and sequestration of carbon, carried out through the photosynthesis of trees, in schemes that essentially monetize and financialize nature under the aegis of the “restoration” economy, linked to the carbon and biodiversity markets. To illustrate this horizon, the Brazilian National Bank for Economic and Social Development announced that it plans to finance the restoration of 6 million hectares in the Amazon by 2030 and a further 18 million hectares by 2050, and that it expects to rely substantially on investments from the private sector and the capital markets [who are interested in carbon certificates].

Over the past few decades, the central and unavoidable debate on the transition away from fossil fuels has been overshadowed in negotiations by the role that ecosystems play in regulating the global climate system. Evidence of this is the growing scientific, political, and economic commitment to the cost-efficiency, effectiveness, and scalability of nature-based solutions, as well as the mobilizing force behind such solutions as a way of engaging countries and territories of the Global South to contribute to a global effort in a new economic cycle. In this new cycle, rainforests are priority territories because, from the perspective of natural sciences and the provision of ecosystem services, they are areas of vast productive potential and hold a strategic asset for this new global economic cycle driven by decarbonization, in which forests are now a global financial asset.

From a critical perspective of political science and the sociology of climate change, this emphasis has brought with it a new set of contradictions regarding new forms of value generation related to emerging businesses and economic opportunities arising from mechanisms for financing and combating climate change, driven by new historical patterns of accumulation, expressed through markets based on the fictitious commodity of “carbon.”

The occasion of COP30 represents a historic opportunity for the Amazon to directly confront the contradictions of both the current destructive development model – aiming to reverse the trajectory of deforestation – and the externalities of climate governance, as well as the impacts of false solutions.

The true solutions to climate change lie in guaranteeing access to land for Indigenous peoples and local populations, ensuring territorial sovereignty, and safeguarding local productive practices aimed at sustaining ways of life rooted in the territory.

It is necessary to avoid the “breaking point” of the Amazon rainforest system, as well as the drivers of violence linked to the advance of false solutions, the financialization of nature and carbon markets, the expropriation, enclosure, and privatization of land and common goods, and the violation of territorial rights and the sovereignty of peoples and populations around the globe. The true solutions to climate change lie in guaranteeing access to land for Indigenous peoples and local populations, ensuring territorial sovereignty, and safeguarding local productive practices aimed at sustaining ways of life rooted in the territory. It is on the survival of socio-biodiversity that the reproduction of the biome ultimately depends.

The article was first published in the Brazilian Amazon Atlas.

See the Portuguese Atlas version here.