This is the story of one Cambodian fisherman whose case stands for those of thousands of other men being forced to work on fishing trawlers.

In 1989, Typhoon Gay wreaked havoc in the Gulf of Thailand. As a result of the severe storm, 200 fi shing boats sank and hundreds of Thai fishermen, mainly from the poorer regions of the Northeast, died or went missing. Driven by fear, the national labor supply in the Thai fishing sector virtually collapsed almost overnight in the wake of this unspeakable tragedy. Boat owners were forced to seek alternatives in the region.

They began to fill the gaps left by the absence of the Thai workforce with migrant workers from Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos. Since then, the Thai fishing industry has grown considerably, and with it the hunger for migrant labor. Criminal networks of brokers, often in collusion with the authorities, continue to secure the constant supply of trafficked human beings to the Thai fishing sector. This is the story of one Cambodian fisherman whose case stands for those of thousands of other men in many villages around the country.

Background

I first met Prum Vannak at the end of December 2009 in the police station of Mukah, a small coastal town in the Eastern Malaysian province of Sarawak on the island of Borneo. At the time I was working for the Cambodian NGO LICADHO, which, with the assistance of a network of partner organizations in the region, was trying to assist Cambodian fishermen who had been trafficked to the Thai commercial fishing fleet. Many of the Cambodian fishermen forced to work on Thai long-haul trawlers in the South China Sea "jumped ship" after having spotted land off the coasts of Sarawak, Sabah or Brunei, following months of exploitation and abuse on the high seas. These men literally attempted to swim to their freedom and, what they all hoped for the most, expeditious and formal repatriation to their families back in Cambodia.

Instead, what awaited most of the fishermen who were fortunate enough to reach the shores was being re-trafficked to oil palm plantations in Sarawak or "repatriation" through established networks of brokers who extorted money from the victims’ families in collusion with the authorities. In that context, the case of Prum Vannak was nothing out of the ordinary. LICADHO and its partners had received hundreds of similar case notifi cations over the years. Yet, to some extent, the case of Vannak turned out to be rather exceptional.

Life in Cambodia

Vannak had spent his childhood and adolescence in Kampong Thom province after the end of the Khmer Rouge regime during, what he called, the time of "Vietnamese occupation." He remembered having received his first pencil from a Vietnamese soldier when he was a kid. He had always liked to draw. Since his parents could not afford schooling for him, they sent him to live with his grandmother, who supported him throughout his primary education. At the age of 14 he left his home and started to travel around Cambodia, sleeping in pagodas. He became a monk and later joined the army. After his time in the army, he travelled to the town of Siem Reap to study the ancient stone reliefs in the nearby temples of Angkor Wat, and subsequently learned the craft of stone carving. For some time, he was trying to make a living as a stone carver, which did not earn him enough to support a family.

In the meantime he had married, and at the age of 29 he was soon to become a father. Worried about his family’s financial situation, and short of money to cover the expenses to be incurred by the birth of his first child, Vannak left his home in June 2006 in search for temporary work along the Thai-Cambodian border. He knew this region quite well, since he had worked there before as a seasonal laborer. He told his wife, who was seven months pregnant at the time, that he would return before the birth with the much-needed cash. However, to his great disappointment, no work was available at the time he arrived. In that difficult situation, he was approached by a villager who told him that he could help him find a farm job just across the border in Thailand. A broker was called to arrange the transfer.

Trafficked across the border

Vannak reported that he was smuggled across the border at night-time in a large group consisting of men, women and children. On the Thai side, a number of pick-up trucks were waiting for the group. Vannak remembered that the people were "stacked like firewood" onto the loading areas of the trucks, before being covered by a tarpaulin. The car was driving the entire night, deeper into Thailand. This was the first time Vannak realized that something was terribly wrong.

When the truck finally stopped, a group of younger Cambodian men, among them Vannak, was taken to a house, where they were locked up together in one room. The house was heavily guarded and no one was allowed to leave. After a short while in captivity, Vannak and some of the other men were given seaman clothes and were escorted to a nearby harbor area, where they were forced to board a fishing trawler. At this time, Vannak was unaware that he had been taken – like many other Cambodians before him – to a guarded compound in the Thai province of Samut Prakan used by traffickers to sell their human booty to the Thai long-haul fishing fleet.

At this point, Vannak only knew that he was in serious trouble with no chance to escape, yet still oblivious to the fact that his ordeal would last almost four years. The trawler left the port shortly after and travelled to its fishing grounds in the South China Sea. On Vannak’s boat were twelve crew members of various nationalities, including Burmese, Thais and Cambodians. The captain, the boat engineer and the crew foreman were all Thai nationals, and they carried guns.

Exploitation on the fishing trawler

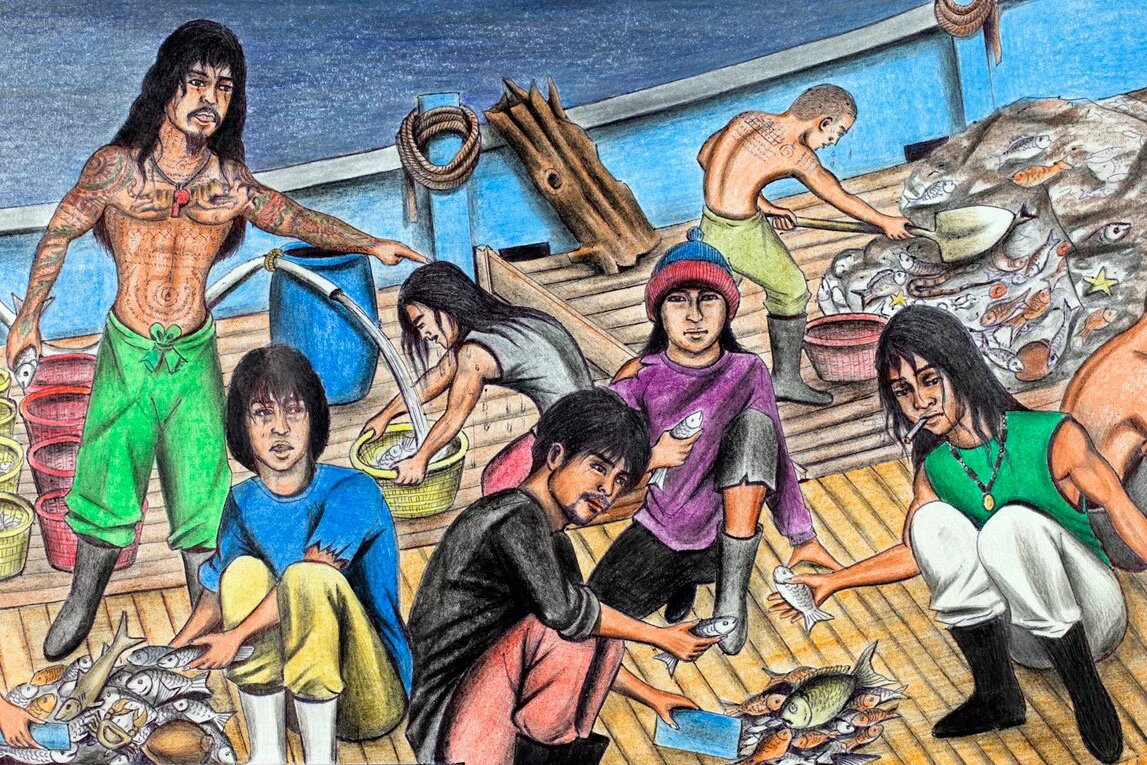

Vannak had to endure various patterns of abuse and exploitation aboard the vessel. He was beaten by the captain. He had to work even when sick. There was no medicine on board for the seamen. The crew had to constantly attend to the two nets that were brought out at intervals on each side of the boat, then unload and process the fish. During down-times, the men were forced to mend the nets or do repair work on the trawler. The crew rarely had more than three hours of rest per day. The threat of violence, beatings and other forms of degrading labor conditions characterized Vannak’s entire time on the trawler, aggravated by the fact that he never received any payment for his work.

Since his fishing trawler was regularly approached on the high seas by what Vannak called bigger "mother ships" which took the catch to the fish processing facilities along the Thai coast, while supplying his boat with food, water, diesel and fresh crew, Vannak never stood a chance to leave his floating prison. His pleadings with the captain to allow him to leave on one of the mother ships were answered by beatings with a rod made of a stingray tail. The first opportunity to escape came after three years on the trawler.

Escape and re-trafficking

In August 2009, his boat was anchoring close to a clearly visible coastline. Vannak and another crew member decided to try their luck and escape, although they were completely unaware of the exact location of the boat. To minimize the risk of getting caught, they agreed to "jump ship" at night-time. They marked a spot on the side of the ship facing the coastline and secretly prepared two empty plastic containers as flotation devices. It was pitch-dark when they plunged into the sea. Vannak said that he was in such a state of panic that he forgot how long it actually took them to reach the shore. The next morning, the two escapees were spotted on the beach by a group of men who took them to the nearest police station.

At this point, Vannak learned that they were stranded in Sarawak, Malaysia. At the police station he tried to indicate to the officers that he was from Cambodia and that he wished to return home. Sometime later, several men in civilian clothes entered the police station and started to talk with the officers. Vannak and his friend were taken away by these men in their car. They dropped them at an oil-palm plantation, where Vannak and his friend were forced to work. At the plantation they met several other former fishermen from Cambodia, Myanmar and Thailand who had jumped ship as they did. A new round of trafficking and forced labor had just opened up for Vannak.

The return

In late November 2009, a fight broke out on the plantation. Vannak and a fellow Cambodian were attacked with a machete and suffered severe head injuries. Being unable to work and of "no value" anymore, the plantation manager approached the police to turn Vannak and his friend in. At this point, the police authorities in Sarawak informed a Malaysian civil-society organization known to assist foreign migrants in distress. This organization, a network partner, immediately notified LICADHO of the cases. This was the time when we traveled to Mukah to meet with the police authorities, Vannak and the other man to build their cases and lobby for their repatriation.

On these trips, we made efforts to visit as many police stations and detention centers in Sarawak as possible, and usually encountered dozens of other Cambodian fishermen trapped in the same situation. It is important to note that at a regional level, Malaysia’s 2007 Anti-Trafficking in Persons Bill (ATIP-Bill) ranks among the most advanced pieces of legislation in terms of victim protection. Unfortunately, the ATIP-Bill is rarely applied by the Malaysian authorities that routinely turn to the punitive sections of the more rigid Immigration Law in dealing with cases of trafficked foreign fishermen.

LICADHO’s role under the given circumstances was to prepare case files and convince the authorities to repatriate the Cambodian fishermen under the protective provisions of the ATIP-Bill in lieu of sentencing them to prison terms and caning them under the Immigration Law. Even more importantly, besides the legal efforts, the role of the civil-society networks is to ensure that the police and immigration authorities in both Malaysia and Cambodia have to expect regular outside scrutiny of the handling of individual cases.

Having a case file as trafficking victim, including a proper name and an individual case story, simply means a higher level of protection for these men. What usually happened after the "illegal Cambodian migrants" had served their respective sentences – in most cases three months imprisonment and one stroke with a cane – was that they were approached in Malaysian immigration detention centers by brokers who cooperated with the authorities. These brokers told the detainees that they would only be able to return home if their families in Cambodia bailed them out. Once the brokers had the contact details of the families, they informed a member of their trafficking ring in Cambodia who approached the families for the money.

The vicious circle

This system worked fairly well. After the payment of the ransom, the repatriation occurred usually within one week. At the time I was working on these cases, the per-capita "release rate" for a Cambodian fisherman in Malaysia stood at roughly 400 US Dollar, which was an enormous amount of money for a rural Cambodian family. In many instances, the extortionist schemes led to new rounds of indebtedness, forcing another family member into insecure migration to make up for the loss. Through their interventions, LICADHO and its partners hoped to at least break the vicious cycle of multiple re-trafficking and prevent that the families of the trafficking victims had to pay a ransom for the return of their loved ones.

Vannak eventually returned home in the spring of 2010 after long and drawn-out repatriation procedures. For the first time he saw his daughter who was born two months after he had left his home in 2006. His talent as an artist helped him to deal with his traumatic experience. He began to draw his story. Through his powerful images, starting with his family, the people around him gradually began to understand what it really meant to be a slave laborer on a fishing boat.

Vannak continued to advocate for the rights of migrant fishermen with the help of his original artwork, reaching ever wider audiences. In recognition of his tireless efforts in the fight against human trafficking, Vannak received an award by the US State Department in June 2012, in a ceremony presided over by the then Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton.

This article was published in Perspectives Asia: A Continent on the Move