Social media in ASEAN has quickly evolved from being a passive tool for knowledge consumption and entertainment to an active mechanism for change.

This article is part of our special on Digital Asia.

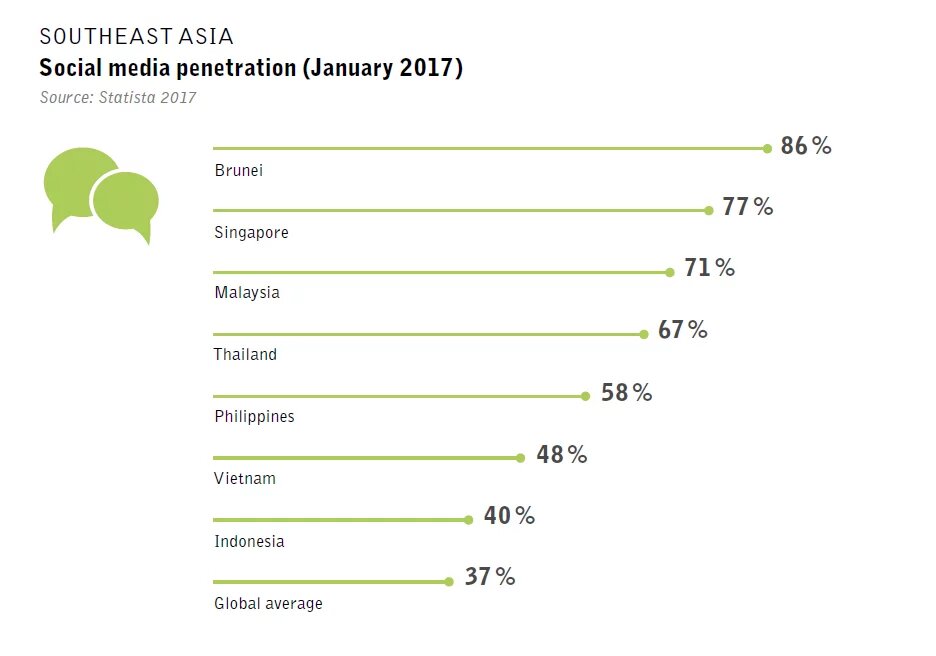

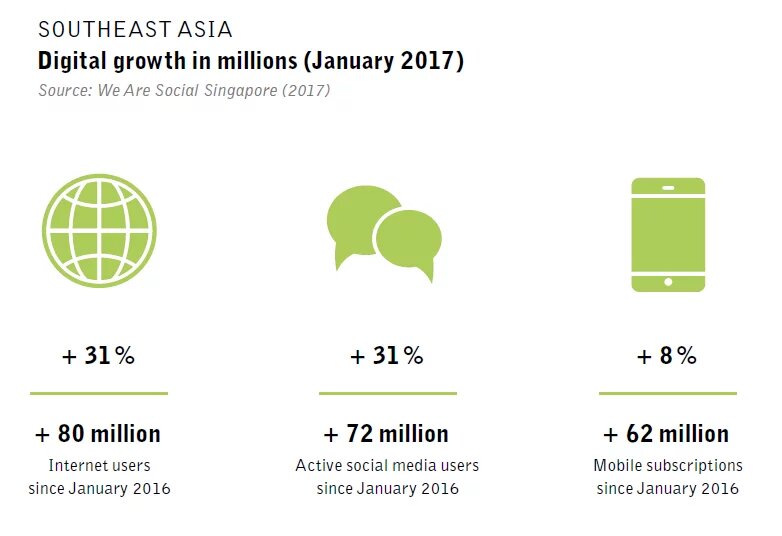

Southeast Asia is no stranger to the inevitable impact of the internet. In fact, most parts of the region have a higher internet penetration rate than the rest of the world. The Philippines is considered by many studies to be the social media capital of the world.

Even Myanmar, which had difficulties connecting to the world not even a decade ago, has been enjoying the highest growth rate of social media users among its neighbors. Internet speeds in Singapore and Thailand – two of the region’s main economic hubs – have surpassed global standards for average speeds.

The campaign of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) for a more integrated community seems outdated, considering how people already connect and interact in cyberspace. Despite increasing rates of migration, people can still communicate with friends and family through programs such as Viber, Line, and WhatsApp. Mobility has also become more hassle-free through instant services provided by online transportation applications such as GoJek (Indonesia), Grab, and Uber.

The internet gave birth to a generation that could instantly engage with the world. Social media provides people with a platform to connect globally with like-minded people. Popular sites such as Facebook and Twitter also allow people to be part of the discourse and movements via online groups, memes, and hashtags. Furthermore, YouTube has produced not just celebrities, but also people of political influence.

Regulation of online activities

People who are silenced, marginalized, and powerless have indeed found an ally in social media. However, many governments deem this phenomenon to be threatening. This digital revolution has pushed many ASEAN governments to regulate online activities in the pursuit of protecting “social harmony” and “national interests and peace.”

According to Freedom House, the governments of internet-savvy Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore have actively censored topics such as criticism of authorities, political satires, and social commentaries. Controversial social issues surrounding the LGBTQI community as well as religious and ethnic minorities are also being scrutinized in Vietnam and Indonesia. Interestingly, the Philippines, which has the slowest internet speeds in ASEAN, enjoys greater freedom of internet use and interaction.

One prime example of government insecurity surrounding the power of social media is the case of then 16-year-old Amos Yee. During the national mourning for Lee Kuan Yew in 2015, Yee shared his “unconventional” thoughts about the late Singaporean founder on YouTube. Both the government and its loyal supporters found his video disrespectful and offensive.

The Singaporean government eventually pressed charges against him, and he was temporarily detained. Yee recently filed for asylum to the United States to escape harsh penalties and social persecution. Despite this, Amos was able to gather support from within and outside Singapore via online platforms that had gotten him into trouble in the first place.

The social and political might of social media: A closer look at Indonesia and the Philippines

In recent years, the internet has contributed a great deal to human rights and fundamental freedoms as well as to the extensive progress of social knowledge in most parts of the ASEAN region. Indonesia and the Philippines – two of the more advanced democratic nations in the region – have been witnessing the various effects of social media on their respective governments and people.

Millions of Indonesians and Filipinos currently turn to social media platforms for their daily dose of news, gossip, entertainment, and, in a more disturbing uptick, their political discourse. With such a massive and vigorous social media presence, how is democracy framed in high-speed communication in these two ASEAN countries?

Indonesian President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) is the most social-media-savvy among ASEAN leaders. His campaign for presidency utilized social media in its early stages. As president, he posts video logs, as if in real time, to inform the public of his activities – be it having dinner with the King of Saudi Arabia or arm-wrestling with his son.

This enabled Jokowi to reach millions of young voters. Social media proved to be an asset in Jokowi’s quest for maintenance and power by not only creating a connection, but also gaining traction with young voters. Instead of fiery rhetoric and humdrum campaign promises, viral videos and hashtags have proven to be quite the engaging alternative for political discourse.

One notable example deals with the horrendous Jakarta automobile traffic. Utilizing snappy music video editing, one viral video had a song on the time-wasting and soul-draining traffic, matching it to snail-paced bureaucracy. The seamless interconnection of national bureaucratic redress, catchy slang in Bahasa Indonesia, and global pop culture has rendered the discourse of politics easily digestible for young voters.

Jokowi’s easy-going online persona

As president, Jokowi utilizes social media to establish himself as a digital folk figure. With a hashtag like “#AskJokowi,” netizens can directly address the president. In addition, by sharing snippets of his life with millions of followers, he makes citizens and voters feel closer to him. Jokowi’s easy-going online persona was helpful to rally younger voters to support Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok), his handpicked successor to the Jakarta governorship, which is a possible stepping stone to the presidency.

Leading up to the election, Ahok rode on Jakowi’s social media coattails, enjoying considerable online popularity, as evidenced by the number of hashtags associated with him.

In the nearby Philippines, many jokingly observe that the country is ahead of the United States by six months in terms of the online proliferation of fake news – and people clustering toward ideology – instead of facts and “truth in journalism.” These factors were harnessed by entrenched political families in the 2016 elections, revealing the power of social media.This resulted in the election of the Davao City mayor, Rodrigo Duterte, as president, and the near-victory of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. (Bongbong) as vice president. Although Marcos lost his election bid, his role in catapulting Duterte to power has been acknowledged. The Marcoses used nostalgia and internet memes to enhance their image and redirect populist hostility and anger toward the Aquinos, who were perceived as elitist and disconnected.

As early as 2010, memes started to circulate showing the “achievements” of the Marcos regime. These memes listed the infrastructure constructed, the economic gains made, and superimposed photos of a young Ferdinand Marcos, Sr., looking presidential, youthful, vigorous, and like a determined leader.

Set in contrast to the numerous problems and general incompetence of the Aquino administration, this generated nostalgia for the imagined glorious past of the Marcos years. Many of the pro-Marcos memes were misleading and misinformed, but still, many supporters shared and asserted their ideology, foreshadowing the proliferation of fake news.

The Philippine media faces a new obstacle

Furthermore, there have been allegations of the Marcoses employing an online army of “trolls” to clean their names, revise history, and drag their opponents through the mud. One such example was a story of the vice president going to New York to have an abortion. It is noteworthy to frame all of this with the fact that Duterte admitted that the Marcoses helped him to gain presidency. Duterte paid his political dues at the burial of the late dictator in the Heroes’ Cemetery.

Many pro-Duterte posts share ludicrous stories that purport the greatness of the Filipino president. One such post claimed that Duterte had been voted by NASA as the best president in the galaxy – this was shared blindly by some, and scorned and mocked by others. A former government official appointed by Duterte unabashedly shared a photo of a woman crying over the body of a dead girl who was sexually assaulted, and whose body was dumped in the woods.

The post went on to rile against drug users, because the suspect had used illegal substances before raping the girl. Many pointed out, however, that the photo was from a Latin American country, but Duterte passed the photo off as having been taken in the Philippines. He was duly called out, but no retraction or apology was made.

A number of bloggers and social media personalities who are vehemently pro-Duterte have received government posts as well as unprecedented access to the presidential palace. These bloggers disguise themselves as “folk heroes” and accuse the mainstream media of being “paid” – even coining the term “presstitutes” – when news stories are critical of Duterte.

These stories, they claim, destabilize the country. The Philippine media – touted as one of the world’s freest and most raucous institutions following the revival of democracy in 1986 – now faces a new obstacle: deligitimization via online programming, with trolls and pro-Duterte social media users casting doubt on news stories. Furthermore, this has enabled many to adopt a troll mentality and attack opponents ad hominem.

Ever since Facebook became “free,” many Filipino netizens have bracketed their lives and opinions on this platform. However, the only thing that is “free” is navigating Facebook posts; data charges are incurred once one opens a link to a different website. This has created a dangerous precedent of reading only the headlines and comments, resulting in opinions being based on partial information.

The internet in the Philippine context has gone beyond the initial ideal of its creation – as a fount of information – but it has also been used by those with sociopolitical and economic power as a tool for transmitting propaganda and manipulating both the minds and memories of Filipinos.

If there is anything the Philippines can offer the world in terms of social media dominance, it is the following: The country should be seen as a cautionary tale in which “truth” versus ideology are now the basis of content generation. This content generation is consumed by netizens, who have more time to comment and spread (mis)information than to read and verify information.

The story lives on: An evolving culture of online citizens in ASEAN

In recent years, social media in ASEAN has quickly evolved from being a passive tool for knowledge consumption and entertainment to an active mechanism for change. Its effects on Indonesia and the Philippines are telling of how the power of the internet can have life-changing impacts on people, states, social norms, and national laws.

In developing and democratically evolving countries in the region, the internet has become a source of power for the oppressed and ill-resourced. In Cambodia, the public turned to Facebook to express grave concerns over the murder of activist Kem Ley. In Myanmar, Aung San Suu Kyi’s inaction toward human rights violations against the Rohingya people was met with serious criticism from netizens.

The romance between ASEAN citizens and social media lives on. Social media continues to shape a more integrated and digitally savvy regional community. It has encouraged ASEAN peoples to go beyond limitations set by geographic borders, political lines, and socioeconomic realities. At 50, ASEAN and its member states must admit that social media is not just here to stay, but that it is – and will remain – a dynamic force to be reckoned with.

This article is part of our special on Digital Asia.