Women in Pakistan face sexual harassment not only in public spaces but also in the digital sphere. We talked with Nighat Dad, founder of the Digital Rights Foundation, about women’s experiences online and how virtual abuse can be countered.

This article is part of our special on Digital Asia.

Fabian Heppe: Last year, Pakistan’s first social media star, Qandeel Baloch, was brutally murdered by her brother for “staining” the family’s honor. She was known in Pakistan for speaking out on women’s rights and fearlessly expressing her sexuality on the internet. Why did she have to die?

Nighat Dad: Qandeel Baloch was a social media celebrity who first received wide recognition when she auditioned for Pakistan Idol in 2013. Her audition quickly went viral, and she became one of the top 10 most searched persons on the internet in Pakistan. She used her media presence to challenge the norms of a typical patriarchal society by attempting to claim her space online and by commenting on “women’s position in Pakistan.” Even though she had the following of millions on the internet, she still faced online harassment, against which she was particularly helpless. She was eventually killed because a male-dominated society could not handle an outspoken woman who dared to shatter the glass ceilings of patriarchy.

Qandeel Baloch’s case is not-one-of-a-kind. A study you conducted found that 40 percent of women in Pakistan face online harassment.

In Pakistan, women are told not to speak up about the abuse they face because of “what people will think.” The public image of female family members and their exclusive affiliation with a family’s honor makes them even more vulnerable to online abuse. With more than 136 million mobile phone users and 34 million internet users in Pakistan, online spaces have today become the new crucible of women’s safety. Their fear of being subjected to more abuse if they speak out about an unpleasant comment that they received online takes the front seat in their experiences on the internet. Qandeel’s murder is a real-life example of this, and it shows that online harassment is linked with offline consequences. This is why women need special protection on the internet. It has been decades and centuries since women have been free to speak their minds and hearts without fear of getting a hate message from a random person, either online or offline.

With 75 to 80 percent of the users online being men, the digital world in Pakistan is very masculine. How does this affect women’s use of the internet?

Women have consistently been denied access to public spaces because men cannot control their “masculinity” in public. As the use of technology rose, women were also barred from using the internet, because men already occupied the virtual spaces before women had access to it. One reason why women are constantly the subject of online abuse is precisely because they are a minority on the internet.

Pervasive online harassment takes away women’s will to voice their honest opinions in virtual spaces. For instance, I know a girl who only mentioned the fact that her hijab did not protect her from being harassed online, and she was immediately attacked by men until she finally decided to seek help. Unfortunately, these examples are not unique in the online realm. The data I collected indicates that more than one-third of women do not feel comfortable online and cannot share their pictures on the internet. This leads many women to self-censor, including those who would otherwise have the potential to play a part in bringing change to society.

As an online activist for women rights, you yourself have had such experiences and are exposed to online harassment on a daily basis.

Yes. I, too, was one of those women who was at first barred from using the internet. As I began to support victims of cyber harassment, I received numerous death threats. When I decided to take some time away from the internet and deactivate my social media accounts, in the eyes of random online men this was regarded as an attention-seeking move and they began body-shaming me. To some extent, I am, even today, after all this time, still scared of the threats I receive online.

Yet, laws against electronic violence against women exist in Pakistan, and men can be prosecuted if they harass women online. Why do these legal measures not help increase the safety of women online?

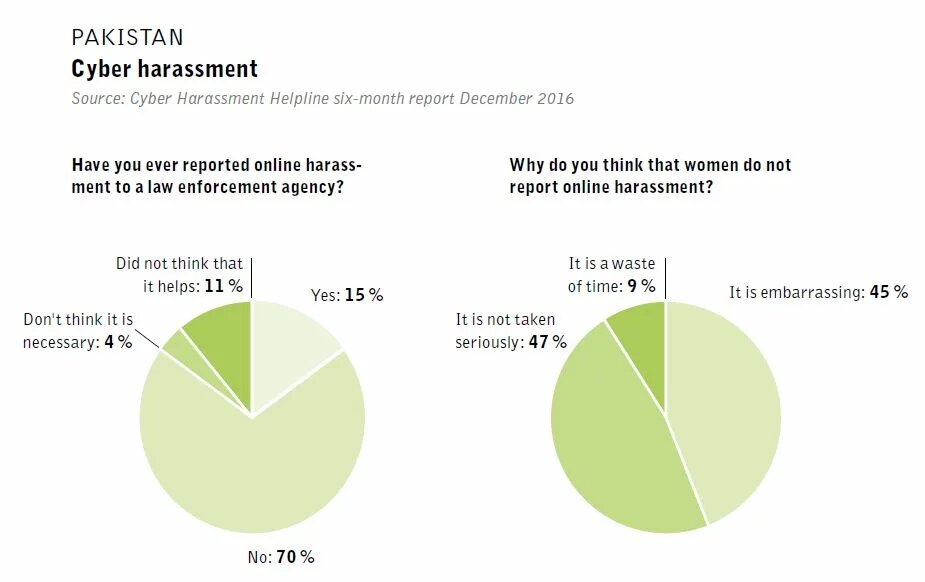

The problem is that a vast majority of women do not know that these laws exist. Our research found that a staggering 72 percent of women are unaware of any such laws. Moreover, 70 percent of the respondents said that they have never reported online harassment to law enforcement, and 47 percent of the whole of respondents of the report said that the law enforcers would not take the report seriously. This particular finding indicates the stigma around reporting online abuse. Young women told us that the Federal Investigation Agency, which is responsible for handling cybercrimes under the law, has blamed the women for being harassed and reportedly asked them to stop using social media.

Your findings seem to contradict the initial promise of the internet for the disruption of old power structures and greater individual freedom. What role do new technologies really play in overcoming old patriarchal structures in societies such as Pakistan?

Although there are setbacks for women’s digital rights, the internet has nevertheless proven to be an extremely useful platform for people, regardless of their gender and sexual orientation. Restricting a major chunk of the population from accessing it is a violation of their rights. Throughout the course of my work, I have come across many women who are running proper businesses online. The internet opens a window to a flood of information for them. These are examples of how they empower themselves within patriarchal structures.

In a society such as Pakistan, where women are not encouraged to be one of the breadwinners and were once stopped from acquiring advanced knowledge on any subject, women are doing exactly the opposite of what is expected of them. They are now using logical arguments against every illogical slur that men throw at them. The national and controversial discussions around Qandeel Baloch’s death show that things are slowly changing.

Qandeel Baloch’s murder was widely condemned by people around the globe. Did the worldwide outcry over her death change the debate about women’s use of the internet in Pakistan?

It’s really unfortunate that a woman had to die to ignite a debate about women’s safety on the internet in Pakistan. Qandeel’s death made people more aware of the offline consequences of online harassment. While a lot of people mourned her death, policymakers moved to pass legislation aimed at curbing online harassment and criminalizing honor killings. The government passed the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act in August 2016 to criminalize hate speech and online harassment.

Qandeel’s death particularly affected me a lot, so Digital Rights Foundation set up Pakistan’s first Cyber Harassment Helpline with the few resources we had. It is my attempt at extending support to those who are in need. I often wonder, had I moved to establish the helpline earlier, would Qandeel have called for help as well? This helpline is my way of paying tribute to Qandeel and the legacy that she left behind – a free woman.

What needs to be done to render the internet in Pakistan more safe for women?

In my opinion, there is a need to properly implement the cybercrime laws in the country, along with gender-sensitizing training for the people handling the complaints of online abuse. More importantly, there is a need to build a support system for survivors and victims of online abuse, because without a network of support, they will not be able to perform even their day-to-day activities. I believe that women need to empower each other in order for them to counter the abuse that they face online and offline.

This article is part of our special on Digital Asia.