Instead of top-down reforms for the media, the countries in Southeast Asia need policies that prioritize the public’s interests. Only with the meaningful participation of civil society can these reforms become sustainable while supporting democratization.

This article is part of our special on Digital Asia.

Pick any corner of the Southeast Asian region and one is bound to find someone swiping the screen of a smartphone and possibly accessing YouTube or social media sites such as Facebook. YouTube is an online video platform owned by Google and is one of the most visited sites in a region inhabited by more than 600 million people.

These platforms have become the go-to destinations for anyone with a mobile device to watch and access all sorts of content, including news and entertainment. The content is shared and discussed with friends and strangers using different chat applications and social media accounts. The advantage of this user engagement is that increasing numbers of people are getting involved in political discourse because the costs for accessing the media have declined significantly.

However, beyond this growing engagement with digital media – and unbeknownst to most users – for quite some time there has been simmering controversy regarding the regulation of content, platforms, distribution channels, and liabilities affecting media and technology companies as well as society.

Governments in Southeast Asia are trying to regulate local and foreign companies, including media outlets (news and entertainment) and platform owners (Google/YouTube) for financial and content liabilities. There appears to be a tradeoff between the benefits that can be derived from these technological advances and the rights that governments are willing to recognize as being fundamental to a well-functioning democracy.

Part of this problem can be traced to the disjointed ways in which the different media platforms and spaces have been “regulated” as well as to the motivations regarding control and profits rather than the public interest. More often than not, there is little public participation in determining the direction of the media industry and choosing what values the public ought to assign to information and communication processes.

These issues arise when looking at countries such as Indonesia, which has almost two decades of reform experiences; Myanmar, which is seen as a newcomer in this debate; and Thailand, where the levels of freedom have expanded and contracted several times over the last few decades.

Punished for expression

Myanmar has some of the fastest-growing metrics regarding the population’s use of mobile phones, internet penetration, and social media use, but the list of critics who are at risk of being jailed there for their online expression is also getting longer. Journalists who once feared a draconian and archaic press and criminal laws are now campaigning against the Telecommunications Law (enacted in 2013), which has implicated more than 70 people for comments posted on Facebook.

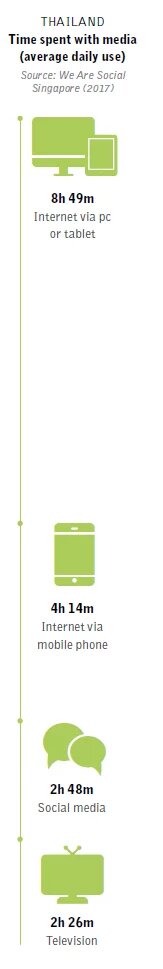

In Thailand, the Computer Crimes Act 2007 became one of the main legal tools – together with criminal laws on lese majeste – to silence those who had been critical of the monarchy and the government following the 2006 coup. In the post-2014 coup, a package of laws for a “digital economy,” aimed at boosting investments and facilitating the switchover to e-services, has mainly drawn attention to the increased powers that the state has acquired to regulate the industry.

Prior approaches to control the print and broadcast media have been retained in – and reinforced by – the laws on media and digital technologies. In other words, societies in Southeast Asian countries are told that they can access the media via its various technologies, but not the rights or the potential for unfettered access and expression.

Even in relatively freer Indonesia, the Electronic, Information and Transaction Law 2008 is now considered to be one of the most notorious tools to stifle expression, as it has been used to drag 35 people – mainly activists and journalists – to court for online defamation. Trends such as these bring to the forefront questions about the media-reform agenda, who the real beneficiaries are, and how people view their relationship with the media and political institutions.

Reforms as strategies

Media reforms are typically understood as strategies to challenge media monopolies, address the negative impacts of economic liberalization in the media sector, and increase public access to information and the means of content production. They involve changes and shifts in institutions, values, and practices.These goals are therefore not only confined to the media sector, as they are expected to support public interest in a democratic society. Among the key indicators for the reforms are improvements in the diversity and independence of the media, people’s access to information, and freedom of expression.

In countries in transition, reforms are often linked to political upheavals or changes that democratic forces use to replace repressive rules that previously controlled political activities and the media. Yet, it is difficult to completely dismantle the old regimes. New power-holders sometimes negotiate and forge alliances with different factions of the previous regimes on the grounds of ensuring continuity or to prevent power-grabs.

This can be seen in the media sector, too, where legislators and bureaucrats of the older regime continue to shape policies, influence agendas, and fill in key positions in oversight mechanisms.

Indonesia and Myanmar have had different experiences with media reforms, although they share similarities with authoritarian regimes that have been in power for several decades and experienced sub-national conflicts. In Indonesia, after the Asian financial crisis in 1997, a people’s movement led to the fall of President Suharto and set in motion reforms that transformed its controlled media into a robust and free one, in which citizens’ freedom of expression was rigorously defended.

Indonesia has been touted in the region as a role model for press freedom, freedom of expression, as well as democratic governance. However, activists and journalists say that the strides made following the reformasi period, although important, have been affected by challenges to political media ownership, the continued marginalization of minority voices, and the recapturing of oversight mechanisms by the state.

The military, which returned to the barracks during the transition, has somewhat re-emerged as a force through its links with today’s business and political elites.

The military regime in Myanmar dominated the media-reform agenda

After the increased pressure on Myanmar from international and local communities to open up economically and politically, the government had to give in and began adopting media reforms after 2012 to guarantee its political survival. Here, observers note that this opening was part of the military regime’s plan, known as the “Seven Step Roadmap,” since the early 2000s.

Coupled with civil society’s lack of experience in advocating for legal changes and their mistrust of political institutions, it explains how the military regime came to direct and dominate the media-reform agenda. The subsequent election of the National League for Democracy in 2015 inspired hope for greater openings and freedoms, but these developments have been put on the back burner.

Thailand has also witnessed a democratization of the media sector as well as political changes since the 1990s, but many of the gains have been lost since the 2014 military coup. Talks of reforms today are concentrated in the hands of the military, which draws its legitimacy from its loyalty to the monarchy.

Many of the changes affecting the media – especially those involving large investments for the broadcasting and telecommunications sectors – began even before the historic political upheavals in Southeast Asia, which continue to form policymaking today. A wave of privatization since the late 1980s – even in military-run Myanmar (as it was known until 1989) – included the media industry.

After years of being under the control of the state, the “markets” were opened to private companies, though most were known to be close to the power centers in earlier times. By the time the internet was introduced, there were growing demands from the public as well as businesses for freer media and less state control of key resources in resource-intensive sectors.

The market approach has dominated the reform agenda, which is led by the states, in collaboration with business interests. This often occurs at the expense of the marginalized and disadvantaged via the patronage-based, neo-liberal market systems that are prevalent in these societies.

Locating civil society in today’s media environment

Although most of the reforms have been top-down – mainly because of the role that governments and legislators play in enacting or repealing policies – broader stakeholder participation could have a significant impact on the outcome. When it comes to the media sector, the main stakeholders are the media owners and journalists, whose representation has been crucial in influencing policies, but who are sometimes viewed as having narrowly vested interests.

To fill this gap, activist and alternative media projects have taken advantage of the various technologies, online and offline, to push back against what they see as moves that would undermine democracy and freedoms. These include the use of the internet to create online discussions and news in all three countries.

Broad-based civil society coalitions have been formed to present alternative draft legislation and campaign against bad laws. These include the formation of a network of community radio stations, democratizing the airwaves in Indonesia and Thailand, and campaigning to reform the telecommunications law in Myanmar, which is one of the few examples there of a social movement in the media sector.

There are lessons that can be learned from the experiences of reforms in the region. For example, the “highs” of the social movement in Thailand took a drastic turn when growing political divisions developed in the 2000s (popularly described as the pro-people “red shirts” versus the royalists “yellow shirts”), making it difficult to form alliances or solidarity across civil society to focus on the common cause of demanding rights-based policies for both the legacy and digital media.

Fragmented identities are not unique to Thailand, as other societies also grapple with this issue. The fault lines in discussions about the crisis in Rakhine State in Myanmar also point to a reform process that may have ignored existing tensions in society. These are also reflected by and in the media – whether through journalism content or social media interactions – and in the ways people use and create meaning using different media technologies.

In Indonesia, many NGOs from the post-reformasi era have struggled due to the lack of international funds that once supported their work, as aid institutions shifted their attention toward strengthening the state and its role in democratization. This affected civil society’s capacity to monitor the implementation of laws and ability to quickly and effectively respond to attempts at derailing progressive elements in the reformed laws.

But activists are optimistic that the online spaces, although at risk, have allowed for mobilization and advocacy to take place without the costs associated with NGOs. In Myanmar, the finite nature of media assistance could also leave many civil society groups and independent media organizations that do good work to promote media literacy in the lurch.

Rethinking approaches to reforms

Reforms in these countries will only make sense if we can strike a balance between the opportunities that arise from the growth of media spaces and technologies, and the historical and structural constraints that have created the gap between those who own the media and those who use it. Negotiations related to the reform agenda usually involve those who have access to the process and hold some power within the communities or societies they represent.

Across the three countries, people who come from different geographical locations, gender backgrounds, and minority identities are excluded, but a more democratic media environment could offer them opportunities for expression, engagement, and empowerment. Ideally, reforms that would bring about meaningful changes should allow for the participation of a wide range of stakeholders, including state institutions, legislators, media businesses, and civil society.

The multistakeholder model used for global internet governance is relevant for discussions and strategies in media reforms because of the diverse and networked nature of the media today. It is a relatively new concept in the traditional media sector, but its application could help in avoiding some of the pitfalls of a state-dominated reform process, as seen in Thailand and Myanmar.

So far, we have seen few, if any, changes in the regulatory frameworks, which has prioritized the public’s interest in democratic processes, since we have entered the new millennium. Instead, the spaces for debates and legitimate criticism are shrinking fast, despite – and because of – the regulatory changes taking place that affect the media.

Whether it is the news media, mobile phone services, or social media, the primary focus ought to be how best these can facilitate dialogues about democratization in the three countries – and across the region. It is encouraging to see that civil society actors have responded to the public’s increased exposure to online and mobile communications and have facilitated such dialogues.

In Thailand, this role is played by news sites such as Prachatai and Thai Publica; Media Inside Out, which conducts media monitoring; and the digital rights group Thai Netizen Network. In Myanmar, several organizations that focus on freedom of expression and digital rights have been active in encouraging people’s participation in campaigns, producing counter-narratives to hate speech, and using data and online tools to check on governance.

They include PEN Myanmar, Myanmar ICT for Development Organisation, and Phandeeyar. Indonesia’s journalists’ group, Aliansi Jurnalis Independen, works with informal networks such as Safenet, a volunteer-driven initiative to monitor online freedoms, and the Press Council to promote press freedom and freedom of expression. In the meantime, netizens are quick to use online spaces to support those targeted for criminal defamation online.

At the end of the day, the individual has the ability to access and produce information and engage in conversations that matter to him or her over any platform, freely and securely. Reforms in the media sector need to place the people at the heart of the agenda, as this will inevitably sustain the growth of these technologies and foster a healthy democracy.

This article is part of our special on Digital Asia.