The world of work continues to struggle with the operational turbulence the COVID-19 outbreak left in its wake, which made the formal sector rethink the workplace and quickly adapt to its new trends. In the face of recession and economic contraction, which increased the vulnerability of Africa's labor force to income losses, unemployment, and food insecurity, the management of organizations was forced to review their business models and put the safety of their staff first by improving human resource strategies and providing flexible working conditions.

As businesses evaluate lessons learned from navigating this volatile economic landscape since 2020, employees are reconsidering work demands. Many of these individual reassessments resulted in a significant decline in workforce participation between 2021 and 2022, known as the great resignation and quiet quitting, with increased workplace stress, burnout, disability, and the deliberate decision to change work-life balance cited as major reasons for leaving jobs.

This change in the dynamics of the labor market, combined with a steady rise in intra-continental and international migration of working-age Africans, has increased competition among employers for skilled workers. Employers are now reimagining and improving leadership to produce meaningful workplace environments to attract and keep the best talent.

This requires a paradigm shift that is both individual and organizational, which the feminist movement has been a leading advocate of in the social impact space, where it has had a notable influence on leadership globally. Through their feminist foreign policy (FFP), governments of up to 13 countries have adopted a feminist lens in policy and development decision-making.

Feminist Leadership

Feminist leadership prioritizes putting a person's or a group's lived experiences at the center of its change model in a way that is relevant and authentic, so it is difficult to give a general definition that applies to all contexts. Continuous self-inquiry within social and political ecosystems and a transformative journey towards creating a just, non-violent, and non-discriminatory world through meaningful connection and collaboration are common experiences among those who practice this leadership. Feminist leadership forges a connection between external goals and internal organizational structures through actions and decisions — personally and professionally.

Evolution of Practice

The feminist movement has historically been at the forefront of promoting workers' rights and equitable leadership structures through the anti-slavery and civil rights movements, and it continues to do so through an unrelenting fight for economic justice today. Before it gained popularity in the development sector, feminist leadership was mainly exemplified by women and women-led movements in the Global South. These women incorporated collective and personal values consistent with the feminist vision into their organizations and leadership practices by drawing lessons from their struggles with dominant Western and patriarchal structures. These values include democratic, participatory, and transformational leadership styles, which, according to research, are more effective and yield better results than autocratic and transactional styles, which men are more likely to apply. The African Charter of Feminist Principles was written and distributed in 2006 to further ground this alternative form of leadership in shared principles and to provide conceptual clarity for effective practice without homogenization. In recent times, feminist leaders such as Srilatha Batliwala have analyzed and theorized the evolution and impact of feminist leadership.

Regardless of gender identity, anyone can be a feminist leader; therefore, feminine or women's leadership should not be confused with feminist leadership. While the former places more emphasis on gender stereotypes related to women's work and interpersonal interactions, the latter is politically and personally concerned with changing economic and social systems in order to stop the propagation of social inequalities.

Here are some feminist organizational principles and best practices that the corporate world and government can learn from in an era where post-heroic leadership is becoming more widely accepted in mainstream workplace leadership models.

Flattening the Participation Field

Exploring the forms and frameworks of power by paying attention to where it is situated and interrogating its use and distribution is essential to the practice of feminist leadership. This is because gendered struggles and global inequality are characterized by an unequal distribution of power within patriarchal hierarchies and its unjust use by individuals and structures where it is heavily concentrated in neoliberal systems. To stop the perpetuation of inequalities, feminist leaders are transparent, democratic, and accountable in the way they exercise power. They also favor flatter organizational structures over hierarchical ones.

The Zamara Foundation, a feminist homegrown organization in Kenya, exhibits collective ownership and use of power through the equal participation of team members in decision-making processes both within the organization and regarding it among partners and supporters.

“Whatever the team agrees on is okay with me. It’s for them to just tell me what they decided for the organization even in my absence, and I'll listen to validate their decisions as long as they align with the organization’s values.” Esther Kimani, Zamara’s founder and director said.

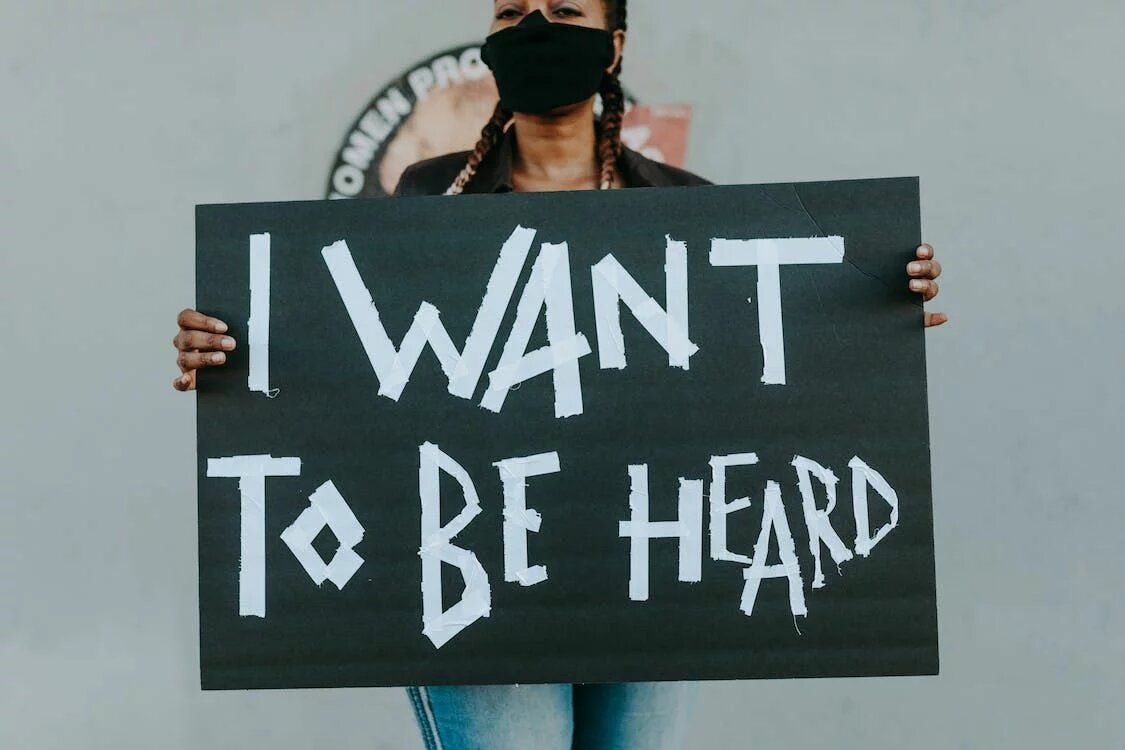

The second most important factor in determining whether employees stay in or leave a workplace, according to the 2022 Global Workforce Hopes and Fears Survey by PWC, is whether they feel comfortable being their authentic selves there. Esther’s transparent and democratic use of power with her team enables them to speak up and interrogate her decisions without fear of sanction, reinforcing their agency.

“The young people I work with are pretty opinionated, which is nice, and I consciously provide space for them to express themselves and challenge my decisions without the fear of being fired.” She explained.

DEI is Feminist

Over the past 65 years, 53 African member states have ratified the Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, the Equal Remuneration Convention, and the Minimum Age Convention. As a result of these treaties, African countries are required to create national policies that promote equality of opportunity and treatment in the workplace without any form of discrimination, implement special measures to meet the needs of individuals due to factors like sex, age, disability, or family responsibilities, and maintain the legal minimum age for employment at 14 years. However, a large number of African employers and hiring managers continue to discriminate against workers and candidates based on their gender expression and sexual orientation, and many workplaces lack inclusive structures for people with disabilities. Additionally, young children are still frequently used as domestic helpers.

Feminist leaders use intersectionality as a conceptual framework for analyzing and addressing the different types of inequalities that women face and how they interact with and reinforce other types of dominance and exploitation that people experience due to their identities. Intersectionality emphasizes diversity and inclusion in the feminist vision of an equal world. Gender diversity in the upper strata of companies is associated with fewer employee lay-offs and unethical business practices, an increase in standards of living and national wealth. Feminism's core values, therefore, include creating social networks and workplaces free from discrimination based on gender, race, sexual orientation, age, ethnicity, or nationality and where everyone has equal access to resources and decision-making. Disabled, queer, and people of all ages are not lacking in spaces such as this.

Sistah Sistah Foundation, a feminist non-profit in Zambia, not only makes sure that its team is diverse but also protects individuals in the organization and those they interact with during its programs by using a feminist hiring process.

“We are very feminist in how we select those we work with as a team. It is important that every team member supports all human rights, isn’t bigoted, and is a feminist or an ally.” Ann Holland, the director of Sistah Sistah, explained. TechherNG in Nigeria and Sistah Sistah are among the feminist organizations in Africa that are instituting inclusive policies such as menstrual leave and extended maternity leave for staff who may require them.

Mindful of Wellness

Feminist spaces are trauma-informed and created with intentional attention to healing and rest. The PWC survey mentioned earlier also found that employees' perceptions of being cared for influence their decisions to leave or remain in an organization. Feminist organizations provide flexible work schedules, healthcare policies, and support, such as mental health breaks, which Sistah Sistah encourages its team to take as needed. The Zamara Foundation also guarantees that team members have access to health insurance that covers mental health care, which includes free therapy sessions.

As part of their commitment to employee safety and preventing burnout, feminist organizations adhere to the national law regarding working hours. “At Sistah Sistah, we believe in people enjoying what they are doing and refrain from taking advantage of their labor. Our full-time staff do not exceed the legal 48 hours, and part-time employees work 30 hours a week.” Ann said.

When team members work overtime to complete tasks at Zamara Foundation, they are given the flexibility that allows for rest the following day, and if employees need to work on a weekend for any reason, they are given a day off during the following week.

Feminist Leadership and African Development

Since the liberation of African nations from colonial rule, the feminist movement has played a vital role in raising awareness of the need for Africa to define and take charge of its development. To do this, it works with government stakeholders and official development assistance (ODA) donor governments. At both the individual and organizational levels, accountability is a fundamental tenet of feminist leadership. Feminist organisations show this through their procedures and by giving citizens accountability tools, like assessments of governments' commitment, to hold the latter responsible for their welfare and the development of their countries. Monitoring the application of feminist foreign policy in countries such as South Africa that have adopted it provides an all-round measurement and tracking mechanism for the government's deliberate efforts to achieve and invest in labor protection, economic justice, gender equality, peace, and climate action, for example—a justification for all African states to adopt it.

In addressing issues that impede development on the continent, feminists are challenging the concentration of power in a small number of national and transnational corporations in the global north, the exploitation and extraction of labor and natural resources, and the privatization of health and education systems.

Fundamentally, the means and ends of feminist organizations' activities are interconnected. In practising their values, members of the movement redefine how development projects are conceptualized and implemented while reinforcing people's rights. Several social justice organizations have developed useful resources to help other organizations and government parastatals adopt this ethical linkage of processes and practices.